Pitching a Fit (Vol. 1, No. 1)

I’ve been experiencing psychological growing pains recently. That’s a cute way to describe the circumstances that landed me on the psych ward for the first time in almost fifteen years, but I guess I could also be specific and say “I recently had a pretty bad manic episode.” Not as cute or poetic, a little more brutal, but more accurate, too.

I was discharged from the psych ward a week ago, and the events that coincided with this manic episode were such that it feels somewhat urgent that I make some big changes in my life. I had to reckon with some deeply self-destructive behaviors, and figure out what led me to try and commit a sort of slow-motion suicide that I only pulled out of when it was almost too late.

I’ve walked away from, or put aside, almost every professional commitment I had in my lap, and I’m reassessing who I am and what I’m all about. Why do I do what I do? Why do I write? What do I write about? For whom? And why?

Sorry, that’s getting pretty heady pretty quickly. To ground us: while the past decade or so has all been about writing on film and TV, I’m reorienting my life to center more on music. And that means writing about music, too.

Except when all is said and all is done, I have a lot of pretty significant blind spots in my musical viewpoint. I like what I like, but there’s a lot I haven’t heard, or engaged that deeply with.

As a starting point, my dear friend and artistic soulmate Ryan Pollie suggested I listen through Pitchfork’s "Top 100 Albums" lists going back to the '70s. This struck him as the right resource to serve as a primer, and so, by way of giving some shape to the exercise, I’m going to get back to blogging first principles: I’m going to write my way through these several hundred albums, five or so at a time. And that begins with the 100th greatest album of the ‘70s...

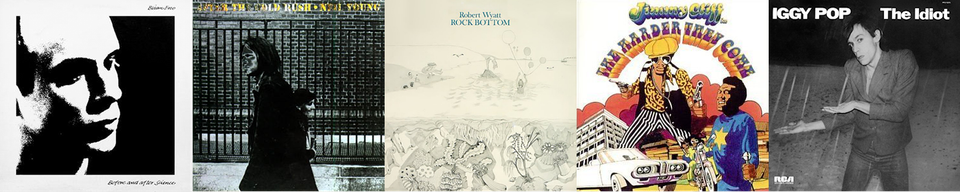

Brian Eno’s Before and After Science feels like a pretty apt way to kick things off, because earlier this year, I took a songwriting course taught by Brian. It was a Zoom class through School of Song, so there’s no shot he ever knew I existed, but man, I got a lot of wisdom out of those lectures. And there was one quote that I’ve kept in my notes app ever since: “Shoot wildly, but have plenty of targets. Instead of thinking ‘I want to make this,’ and trying to shoot to it, just shoot everywhere but make sure there’s a good chance it’ll land somewhere that you can call a target.”

That’s about how I approach my work, and it makes me feel a lot of affection for Brian as an artist even if his music is more cerebrally satisfying than gut-level pleasurable for me. Before and After Science is a sort of ne plus ultra of art rock, putting me in mind of other artists like Devo and Talking Heads. I gather Brian was collaborating with a huge number of artists on this record, and it feels appropriately unwieldy and sprawling. There aren’t many earworms or even hummable melodies, but it’s a bracing record that makes you sit up and think rather than fading into the background.

1977 was an interesting moment for the arts, with Star Wars helping to establish what mass media was going to look like (slick, eye-popping, appealing to as many people as possible at once). It was the year of Rumours, and Before and After Science feels in many ways like the antithesis of something so compulsively listenable. It’s a prickly record that often puts me in mind of Pink Floyd’s more psychedelic tracks; the vocals are arch and the lyrics are rarely straightforward—“sound over sense” was apparently the guiding principle, so looking for logic in the words doesn’t tend to yield much in the way of reward. But it’s a rewarding album overall as long as you’re not looking for pop hooks or anthemic choruses.

(It's also worth noting how insanely beautiful Brian was in this era! He’s dashing in 2025, too, but he had this delicate grace to him in the ‘70s that’s really striking, and captured, all long eyelashes to pursed lips, on the album cover).

From there, we pivot back to the beginning of the decade with Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush. This 1970 album was intended to be the soundtrack for a movie about the Topanga Canyon artist scene—Dean Stockwell had a script, Dennis Hopper was planning to help him make it in the style of Easy Rider. Sounds like a pretty fascinating movie, honestly, but the deals fell through and the script got lost. In the bargain, we got Neil Young’s masterpiece (or at least one of Neil Young’s masterpieces).

I find something immensely warm and comforting about rock from the early ‘70s, and I think a lot of that can be attributed to Almost Famous, which established what this music means—comfort when you’re low; the impetus to adventure if you’re lucky enough to get that call. Young’s arrangements (he has a producing credit, though he was assisted by David Briggs and Kendall Pacios) are simple, heavy on the acoustic instruments. But he does what Brian Eno didn’t care to do: craft hummable melodies you can carry away from the album.

Young has just never been my guy, but he was my wife’s guy back in college, when she would ride the bus from Maine to Massachusetts with him as the soundtrack. I have a lot of affection for him for that reason, but there still aren’t that many Neil Young songs that I find compulsively listenable, and After the Gold Rush doesn’t really move the dial for me on that level. As much as this was meant to be a soundtrack, it doesn’t have a particularly cinematic quality. Instead, it’s an example of country-folk-rock, and a sort of ultimate example of the form. Nobody makes Neil Young-type music like Neil Young, with his high crooning voice and gentle affect, and if you have to squint to make this work as movie music, it announces itself just fine as a classic rock album.

From our time with Neil we move forward a few years to 1974 for Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom, a strange and eerie album apparently made while the artist recuperated from a four-story fall and became used to life as a paraplegic. He composed much of this music “in a trance”—as he put it—in the hospital, but this isn’t wholly and explicitly a post-accident record (much of it having been written before the fall). It’s a dense collection of just six tracks, all of them in the six-minute range. They’re eerie and occasionally upsetting songs, with Wyatt’s gentle voice being used to uncomfortably abstract purposes. But abstraction isn’t always an upsetting thing, as we can see from “Little Red Riding Hood Hit the Road,” which blends an anxious beat and trumpet noodling with bursts of soaring major chords. Appropriately, it’s the longest song on the album at over seven and a half minutes, and by the time Wyatt’s voice comes in, it’s clear we’re going on a very strange journey. The album was produced by Nick Mason, the drummer for Pink Floyd, and this is psych rock in a big way, with possibly even fewer concessions to popular taste than Floyd ever managed. A track like “Alifib” seems to be trying its best to provide something pleasant and listenable only for the effect to be sabotaged by rhythmic panting and the nervous jangling of the synth tones, not to mention the abstract lyrics that come crashing in by the halfway point.

“Rock Bottom” is a term I’ve become acquainted with recently as I try to claw my way back into the light, and it’s a pretty apt term for an album that climaxes with the extensive nervous breakdown of closing track “Little Red Robin Hood Hit the Road”. There has to be a lot of confidence behind the songwriting to record something so anarchic and make it so satisfying. Rock Bottom may have been where Wyatt felt himself existing at this time, but as I was recently told, “The elevator keeps falling.” What we think of as the absolute bottom could always get worse, and the idea of “rock bottom” could be a story we tell ourselves to cushion our awareness of how much worse things could still get. This album feels like decent accompaniment to the experience of reckoning with a rock bottom, Wyatt’s or your own.

Apparently the 97th best album of the ‘70s was a soundtrack, specifically the compilation album recorded for The Harder They Come. I have never seen The Harder They Come, so I can’t really speak to this as an accompaniment to the film, but apparently this is half a collection of new music by Jimmy Cliff and half a bunch of singles compiled from the Kingston, Jamaica reggae scene. It’s a little surprising to encounter a soundtrack on the list of greatest albums, but given that this collection seems to have been a major factor in popularizing reggae for the world outside Kingston, you can’t argue with its significance. There’s also the fact that reggae just sort of bounces off me. I never hate a reggae song, but I never really love them either; it’s never been my genre. But as I try to give this album a full, open-minded fair shake, I have to admit my own narrow-mindedness. If The Harder They Come is a great primer, I’m glad to have encountered it. These songs have a great buoyancy and vibrance to them, and it’s pretty handily the easiest listening I’ve done since starting this project four albums ago. Despite my self-professed disinterest in reggae, this is the album I could most easily see playing again, maybe while driving with the windows down, preferably by the seaside. Sounds like a pleasant way to spend the day.

We wrap up this first entry by heading back to 1977, the year when Star Wars was changing everything and art rock was asserting itself so full-throatedly. The Idiot was partially an effort by Iggy and his producer, some guy named David Bowie, to kick their severe drug addictions. The title was taken from Dostoyevsky, and while I haven't read the book, word on the streets is that it concerns someone so purely good-hearted that the world mistakes him for an idiot. How effective can a person with a simple, good heart be as they navigate a world with this much anger and pain? This, it seems, is the question investigated by the novel. I would not know firsthand, but the idea informs the experience of hearing this album. Mr. Pop was apparently in an exceptionally low place and trying to claw his way back into the light, too. It's nice to know that making music was part of that for not just Pop but Robert Wyatt, as well. Apparently the year before this album, 1976, served as Pop's own rock bottom—at least according to one of Bowie's biographers—and so in those two records, Rock Bottom and The Idiot, we find two guys doing their best to create something beautiful and lasting out of the worst of circumstances. I'm not sure how much of The Idiot I'll be revisiting, it's a little austere and stern in its electrically-heavy arrangements. There wasn't a single track that jumped out at me as demanding to be listened to again soon; I'm impressed by all of it, in love with none of it. But I'm glad to have Iggy and David grab my hand and guide me through their version of the darkness, too. That wilderness has a good beat.

Up next time: Led Zeppelin, King Crimson, Jimi Hendrix, Kraftwerk, and Throbbing Gristle