Pitching a Fit (Vol. 1, No. 4)

Welcome back to Pitching a Fit, a series of posts for which I’m going through Pitchfork’s 100 Best Albums lists decade by decade. For this installment, we’ve reached numbers 85 - 81 on the Best of the ‘70s list…

We start this entry off with a distinctly ominous blast of industrial rock. Wire’s 154 is apparently heralded by a number of great musicians as one of the greatest albums of all time—Robert Pollard of Guided by Voices goes so far as to call it THE greatest, while Johnny Marr of the Smiths pointed to it as a reinvention of rock guitar. That’s nice for those guys, and as always, it’s pleasant to experience the alpha and the omega of a certain type of rock, but boy was this album not made for me. This is rough and creepy music, an aural horror movie, and one listen is plenty for me. The single, “Map Ref 41 Degrees N 93 Degrees W”, is undeniably exciting and powerful, but it’s a bright spot in a sea of heavy chords and tones. It’s intriguing to hear this kind of minimalism, but “intriguing” is about as far as I’ll go in my praise.

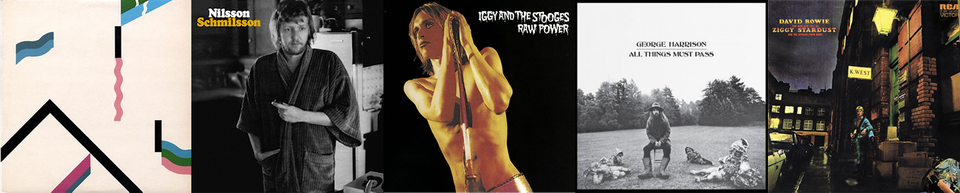

Harry Nilsson’s Nilsson Schmilsson, on the other hand, is an album I will go out of my way to praise. This is one of the most inviting collections we’ve encountered on the list so far—the cover depicts Nilsson in a cozy robe looking vaguely unsettled, and that’s a pretty appropriate imagistic accompaniment to this one. “Gotta Get Up” kicks open the door with a big brass section accompanying an acoustic arrangement; Harry had a knack for clever, warm songwriting but there was always something vaguely anxious behind that warmth, pushing the songs into a territory more rich and strange than his contemporaries. The album takes more than a few left turns—an arguable high point comes in “Without You”, an epic bit of composing (which, granted, can’t be credited to Nilsson) and arranging, with orchestral elements again sneaking in around the margins. This standard is followed by the stranger but no less indelible “Coconut”, each track a type of classic but neither particularly like the other. This double header is chased by a cover of “Let the Good Times Roll” that makes a convincing case for the song as Nilsson’s own (at least in spirit), while “Jump Into the Fire” is a seven-minute jam that builds and builds long past what you’d expect from a 1971 singer-songwriter record. If it weren’t for Joni Mitchell’s Blue, Nilsson Schmilsson might just be my favorite album I’ve encountered so far. As is, it'll settle for second.

Our next album is the second on this list to open with a track familiar from The Life Aquatic—this time, it’s “Search and Destroy”, the opening number off the Stooges’ Raw Power. I can’t say I was ever moved to jump from the movie to the album, but no time like the present; streaming services currently offer two versions of the album, as well as a special edition comprising both. There’s the Bowie mix and the Iggy mix, and the former is notorious for having been done in just a day, but as it’s the legacy mix, it’s the one I chose to listen to for this exercise. I don’t hear anything particularly wrong with it, and quite a lot right with it. This is a rough and rowdy record, guitar and vocals fighting for supremacy with bass gluing everything together and a little bit of keyboard gilding the edges—it’s a marked contrast to the lush Nilsson Schmilsson, and more power to Iggy and the Stooges for it. But also unlike Nilsson Schmilsson, this is a record you kind of grasp the concept of pretty quickly, with the remaining tracks being variations on a theme. If that theme works for you, fabulous, but I found myself longing for some different flavors after a certain point. This is certainly raw power, but it’s not much else on top of that.

Following the Stooges we have another beast of an album in George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass. We’ve had at least one double album on this list, but this is the first triple album, and befitting the sheer girth of the thing, it’s by no means a one-trick pony. Harrison was showing off as many modes and styles as he could, and several of the tracks have come into my life before this, with “Wah-Wah” and “Apple Scruffs” in particular being longtime favorites. I’ve tended to choose George as my favorite Beatle when pressed, which has always felt like a safe choice—John and Paul were too central to the mythos, while George was more the genius in the corner, often seeming under-appreciated enough to make for an intelligent pick. Thus, All Things Must Pass has always seemed like a logical choice for a favorite solo album, and the tracks meet that standard. This one is full to bursting, sporting almost 30 songs, and they’re generally warm and inviting. Some are familiar to the point of ubiquity, but they’ve lost none of their power—“What Is Life” is a blockbuster because it’s just that great, and no amount of use in movies and TV will do anything to change that. If anything, this album could be a case of too much of a good thing, and I do feel that I’ve already plumbed the real standouts for my needs, with the balance being great background music that rarely (not never—the guitar work on "Art of Dying” would like a word) rises to grab my full attention. But that still leaves a dozen or so tracks for me to return to and plumb over the years to come.

This all leaves aside the “Apple Jam” third disc, which feels like it both plays into my “too much of a good thing” point and simultaneously feels like its own album altogether. I’m not sure I agree with the wisdom of adding even more material to this already vast album, especially when the music is this loose—All Things Must Pass came to an ending already, and including an entire additional disc of instrumental jamming strikes me as more indulgent than intelligent. But, on the other hand, this music rocks, so far be it from me to argue with the wisdom of my favorite Beatle.

For the last album of this installment, we pick right up with a favorite song of mine: “Five Years” off David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. This song is a treasure, an elegy for a world with no future, and it’s perhaps not hard to see why it resonates in the year 2025 (or the years leading up to it). “Five years,” Bowie wails repeatedly, “that’s all we’ve got.” It’s a striking and upsetting first song, something you might envision buried further down the track list, but simultaneously something that makes such an impactful statement that using it as kickoff feels wholly appropriate. It’s a cinematic gesture, setting the stage for the sci-fi spectacle to come. This is an album with a clear thumbprint of artists like the Velvet Underground that Bowie had been communing with around the time, but it's simultaneously an album with a massive footprint of its own. It sits at a precise intersection of what came before and what was to come. The classics (“Starman”; “Suffragette City”) stand out in bold, but they fit perfectly into the conceptual whole as well. Bowie’s got one of the most distinctive voices of the 70s, both vocally and authorially, and this certainly feels like the peak of a certain type of rock and roll concept (not “rock opera” per se, the Ziggy character and journey having been arrived at too late for that designation to make sense). It’s such a timeless album that seeing a year attached to it almost feels apocryphal. This album can’t have done anything as pedestrian as “come out” in 1972; it always has been and always will be.

Up next time: more David Bowie, Randy Newman, Fela Kuti, even more David Bowie, and Blondie