This is My Fascination, Vol. 4

For this latest edition of my favorite thing I do, I talked to Reuven Glezer, who answered my open call for fascinations on Twitter. “I'm profoundly obsessed with magic (both the stagecraft and the belief systems),” Reuven wrote. “Sounds like a newsletter to me!” I replied. A few days later, we met up on Zoom for some magical discussion.

So I did not do any kind of prep or anything, because it’s such a broad topic that I just wanted to hear how you would start.

I've been fascinated by magic my entire life. Everything from the concept of it to actual theatrical magic. I'm a magician by trade—one of my jobs is, I'm an illusions designer for New York theater, which is a very fun job, if stressful for dumb reasons. But the dumb reasons are usually economic, and not craft-wise.

Well, why don't we start at the very beginning? Was this a childhood fascination of yours?

It started when I was in elementary school. My school had begun doing something called “after school time,” which is basically, like, join a club. And I joined a magic club, and the magic club was a fucking lie. It was a science of magic club. And we didn't really do anything except make things like oobleck and talk about the science of magic—which was fascinating, but I was in the fourth grade, I was like, I want to do this! To my lovely science teacher’s credit, she was very much like, Here's some famous magicians, and here's how they did their tricks. Here's how they held their breath for a long time. And that was cool.

But it sparked this lifelong interest in fantasy literature, and magicians, and magic. I was part of the Harry Potter generation. I waited for my Hogwarts letter when I was 11. And then that relationship got complicated, as you can imagine. But it was so fascinating to me, because I grew up in a very Jewish household. And I didn't know until I was in that club that Harry Houdini was Jewish. And that was sort of what set me off on that path. I became a Houdini obsessive.

And so that's sort of where I think it started, if I had to pick a pinpoint in time—it was being bamboozled by my very nice science teacher.

Is there a theory of magic? Where do we go scholarly-wise?

That's a tricky question, because there is a lot of scholarship about magic. There are magicians who have done things in terms of performance theory, and how to affect an audience's perception of your tricks, and just the craft of your tricks. There's Max Maven, who was a famous mentalist, who passed away recently. He wrote this book called Parallax—it’s a collection of his essays about magic, and it's hard to find, because the thing about magicians is, getting their books on theory is always tricky. They're always like 50 bucks or something, because they're cagey about their secrets.

There’s are a lot of theory and practice on misdirection, on how to fool an audience, how to fool a single person, principles of close up magic, of cardistry, of all these practices and disciplines that have been built on by magicians of yore. S.W. Erdnase wrote this book called The Expert at the Card Table, which is kind of the Bible for card magic. It's the first book you read when you do card magic, and nobody knows who he was. It's a pseudonym. It's one of the great mysteries of magic, which I think is hilarious. Of course the guy who taught everyone the tricks is a secret of some sort.

If you kind of distill it down to its most basic form, it’s the performing art of deception.

I would say magic is the art of convincing you that I've done the impossible. I think that's one of the founding principles: you're trying to do something where the person in front of you is like, How did that happen? It starts small—you, as a person, are naturally ingrained to enjoy impossibility, from when you're a child and you play peekaboo. You don't have object permanence yet, and you're like, Wow, where did this bigger human come from? How did Daddy do that? It is the art of creating the impossible, and convincing you that I've done the impossible. That's probably the deep essence of what magic is.

I think you mentioned the history of magic as one of your areas of interest, right?

When I got into it, I got really into folklore and mythology, and that was a natural extension of it. I had books and books and books of folklore, mythology, and bestiaries. I begged my parents all the time, and they would be really confused, like, Why are you into this stuff? And I was just like, Because it's cool! I want to read about dragons, come on! I had a very wide body of knowledge of mythical creatures and types of wizards from all sorts of fictional sources, and historic sources, and folkloric sources. I think I had this deep hope as a child that magic was real, as every child does. I was hoping one day that I would discover the secrets, and that, actually, I could make a card appear out of nowhere. But no, the thing about all magic tricks is that there is some level of extremely basic logic to them. My favorite thing is when someone asks me how a trick happens, and I ask them, How do you think it happened? And they have 70 goddamn steps! And the answer is, it's actually in four steps. And it's fun watching someone go, But it must be this and this and this. It's like, actually, you trying to be clever about it is not going to help. You have to accept that it's much simpler. And that's where people get tripped up. I think that's where people find it to be dorky. Because they can't be the most clever person in the room.

So can you tell me a little bit about your work?

The thing I mainly do in theater is, I'm a director and a writer. And what had basically happened was that I hit a rut. And then I went to see a show by this theater company in New York called Nightdrive that does big, spooky, impossible plays. And one of the artistic directors, and the guy who directs all their shows, and co-writes all of them, Skylar Fox—I hit him up after I saw a show of his being like, Hey, could we meet up? I loved your work, I'd love to talk about it. And this was when I was a young, budding director—I'm still a young, budding director, I'm only 26—and I was really interested in how he did the show, and the stuff he was doing, because I really loved what he'd done. And his main job at the time was, he was the American associate on Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, the Broadway production. And we met for coffee, and struck up kind of a kinship. He’s still a good friend and mentor, and he was like, Reuven do you know magic? And I was like, Yeah, I do, I’ve done it. And he was like, Do that, it'll help pay your bills. And so that's where it started: Oh, I could incorporate this into my work as a theater artist. And then it became a thing where I was studying the craft of making effects for theater, and figuring out things like having someone disappear. It was a lot of actually sitting down and figuring out the mechanics of it. I joke to my engineer dad—Hey, Dad, I’m finally an engineer, I engineer magic! He’s like, That doesn't count.

Seems like it should count. I probably jumped ahead too much, though. You should tell me about how you you learned the craft.

I didn't have a teacher. It was a lot of YouTube videos, people being like, Here's how you pull up, here's how you do a false cut, here’s how you shuffle cards correctly, here’s how you deceive people, here’s how you do sleight of hand. And this is something I do with a lot of stuff I'm interested in, I tend to fully teach myself. I'm very autodidactic. I prefer to sit in a room for four hours and just try things by myself. And I invariably get deeply frustrated. But that's the name of the game, I think.

Did you do any performing before you then rolled that into the theater?

I briefly did a party or two, and I swore never to do it again. I have anxiety, so I actually hate performing. I'm a really nervous performer—whenever someone asks me to pull out a trick, I'm like, you're making me really nervous. And people don't believe me. I love the technical of it. I can show you how to do a trick. But I never, ever want to perform in front of an audience ever again. I worked a party recently, and it was such a draining experience. It was just a whole situation where I was like, I don't feel comfortable with all these people coming up towards me and asking me to do things for them, or to show them something. And I was only doing it because I really needed the money. It was one of the things that reminded me why I didn't do it, and why I preferred being a backstage craftsman of the impossible, rather than a front of house guy who's wearing a suit and convincing you that I have spoken to your Great Aunt Becky.

Can you tell me about some of the theater work that you have done?

Some of the things I've done I'm not privy to talk about at the moment, because it's in the works. But I've done things like making fire appear out of people's hands. I've done ectoplasm tricks, which are one of my favorite things. That drove me fucking crazy, because I spent a lot of time at Sephora with a lot of glow in the dark makeup. It was a mess. I've done card tricks before. The thing that always gets people is pulling something out their ear, no matter how old they are. I once went to a karaoke marathon, and I kept pulling lollipops out of people's ears, because I had them left over from my day job. A friend of mine was like, You can't just do that to me. They still loved it. It was a rollicking good time to just see people—even people who claim to be jaded against it, you still execute it, and they're like, Wow!

So can you tell me any examples of particularly excellent magic that you've seen on stage?

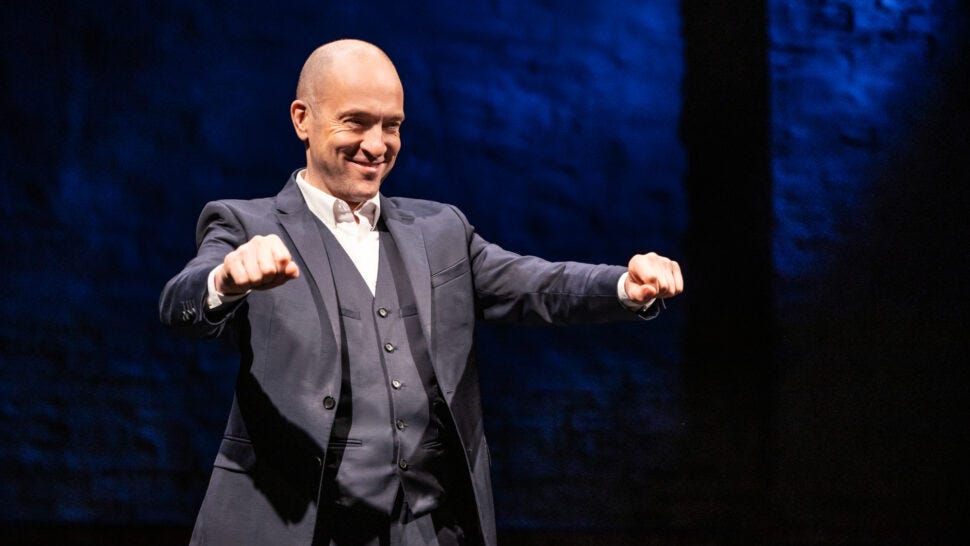

There's this one magician I'm obsessed with. His name is Darren Brown, he's a mentalist based in the UK. You can watch a bunch of his shows on Netflix and YouTube. But the one time he came to the States was with a show called Secret, and I went when it came to New York. It came twice, it was off Broadway, then it went to Broadway. And if you go to a Darren Brown show, you will end up on stage. Like, there’s a good chance, and I was one of those lucky—or maybe unlucky—few.

This is 2017, I think, and he somehow got me to draw a picture of a snake without my own realizing. I'm still not sure how he did it. But there's a trick in the show—this is a spoiler, but I feel like after years, maybe it's not spoiler anymore. If I'm remembering correctly, he's facing away from the audience, and someone in a gorilla suit crosses the stage. And then the head comes off—it's actually Darren. He's actually in the suit. And that was the intermission of the show. That ended Act One. And that really blew my little mind when I was in college, and I was not really doing magic yet professionally. But it was one of those moments where I was like, I want to do that. And that's why it fascinated me for my entire life—the crafting of the impossible, that magic, at its finest, is. It is a moment where the audience goes, I cannot solve this. And it is the joy of being unable to know.

It strikes me as kind of a niche thing. Has there ever been a moment where it was, like, widespread and accepted? Jim Henson is my guy, and puppetry is, like, the most uncool thing in the world. But in the ‘70s, it was kind of a phenomenon for a little while. Has there been a moment like that?

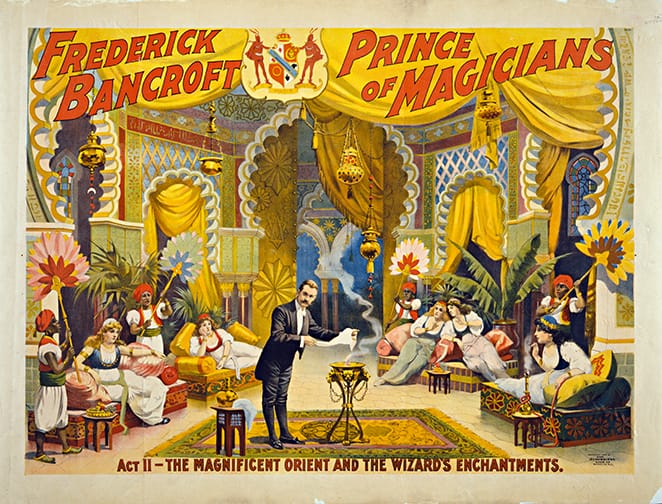

I don't think so. I think when people think of magic, they think of big celebrity magicians, like David Blaine, or Criss Angel, or David Copperfield, or Penn and Teller, who are all very talented craftsmen. Maybe not the best performers, but really great at what they do. But it has this rap of being a big Las Vegas circuit thing here in the States, whereas in the UK, it's a lot more thought of as a craft. From my friends who've done theater across the pond, it's much more recognized as a specialization, whereas here, it's much rarer. There was a point where I could count every professional illusionist who worked in theater in New York. But more widely, people just knew the big Las Vegas people, and it wasn't really in vogue at all. So no, and I think that's what's kept it niche, because it's so glammed up in that specific way that it's a little bit gross. And don't get me wrong, I've seen some fantastic work by so many magicians. But the biggest public perception of doing magic is, it's kind of a thing that dorks do, who have a lot of time on their hands, and have no friends. And I think that was the stereotype of being a magician growing up. But everyone I know who is actually a magician, that it is their life, and they're such brilliant craftsmen, and fascinating artists—and they are artists. That is also a thing people forget. Magic is an art. It's a very technical art, but all arts are technical arts when you think about it.

Is it something that you would like to see get more of a cultural cachet, and less of a dork air to it? Or are you comfortable with what it is culturally?

I am honestly quite comfortable with where it is, because I feel like some things deserve to have their own little corners. If it somehow caught on, and suddenly everyone was into magic, I would love that. But I think because it's something that has a slightly higher barrier to entry, because of how much technical proficiency [is required], people are just like, It's not for me. Which is fine. But if it does reach a greater cultural consciousness, I think it's gonna take, like, an HBO series or something, like the way The Queen's Gambit made chess cool again. As a lifelong—if extremely terrible—chess player, I was like, This is kind of fascinating, that everyone is suddenly into it again. I'd love to see it happen. I don't think it will. But if it does, that would be so damn cool.

In my mind, there's two perceptions of magic. One is the very ephemeral kind that we hear about in fairy tales, that I think people long for deeply. That's the kind of thing that fascinates me. That's why I love Guillermo del Toro’s work so much: I think it hits on a base desire for magic to be natural. I remember when fairy tales were suddenly a huge phenomenon again, when there were TV shows about fairy tale characters, and fairy tale detectives, and Fables, the comic book series that I love—I think it's a brilliant, brilliantly written series. But the kind of magic that requires you to give up a sense of knowing, I think, is something that people don't want to vibe with as much. It's fascinating to me, people are always reluctant to not be the smartest person in the room, or to give up their illusion. And there are people who get frustrated with it. I remember I had this hilarious experience of a guy I met at a show who was really trying so damn hard to solve a trick, because he thought he was smart enough to do it. And he was extremely wrong every time, and I just remember thinking, You would have so much more fun just not knowing. And that kind of thing is a much more pervasive cultural perception of the magical arts. It doesn't help that magicians are secretive, tricky people. I say this very lovingly, but they are protective. That's why books about magic theory and performance theory and craft and design are expensive.

And why you can't get into the Magic Castle.

The magic circle is one hell of a circle. It is a very tight chain.

We’ve been thinking about magic in a specific way, but I didn't think about terms like magic realism and magical thinking. I love that idea, magical thinking in particular—that we can look at the world around us and say, No, we're gonna project what we want to instead, is a concept I really love. Do you like magic realism?

Oh, I love it. I love magical realism. I think it's funny, because I remember reading this quote from Terry Pratchett, who is one of my favorite writers, but he said something that I found deeply dismissive, where he said magical realism is Spanish for fantasy, or something like that, which I think is dismissive. I especially love Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the godfather of magical realism. But I think people inherently view their lives through a magical realist lens. They view things through the casual nature of fantasy being interwoven with reality. And I think people are embracing that more in ways they don't explicitly call magical realism, like the uptick of people being into Tarot, or astrology, or reclaiming pagan belief systems. Or trying to be in touch with local folklore practices—I think that is, in a weird way, a very American understanding of magical realism, where it's just part of your everyday life, but it's not fantastical, because it's not considered separate from the norm. It is above the norm, and that's what separates magical realism from high fantasy. I feel like one of the great tropes of fantasy is that you are a normal person who experiences this weird thing out in the great wide yonder. Magical realism asks—and I can I can hear some literary theorists going, That's wrong!—but from my perspective, magical realism is just interwoven. Of course the vines bear the secrets of everyone who's passed by them, things like that. And I think a lot of people, especially young people, now deeply want that.

So it must touch something primal, some need for us, this need to see magic in our own lives, and the world around us, but specifically in ourselves and our own narrative. Do you think there's some primal button being pressed?

Oh, absolutely. I think people inherently need a large a framework within which to understand the world. And for a lot of people, it is understandings of fate and destiny. I think my complicated answer is that we seek answers in our stories, and stories often take us to lands we don't know. And that's where we can release ourselves from the constrictions of reality. It's a war where we can meet the fates and see the strings of fate and ask, Well, how long is my string? And I think for a lot of people, there is a primal need to feel like we are in control of our own destinies. At the end of day, magic is an explanation for a phenomenon. Or at least you can use it as a way to explain phenomena—the reason the crops failed is because your neighbor has cursed you. The reason your child is ill is because the cat you accidentally kicked was actually a witch. I think there's a primal need to be like, The natural world is unexplainable, but I have some secrets and explanations to it. I think people love having secrets. I think they love being in the know of strange things beyond the scope of understanding. And I think that's why a lot of people are so into wondering about, like, Who was the local witch? Why was this local woman thought of as a sorceress? Why were these people hanged in my town in England? I think it's something that compels people deeply to question. But there are also forces in the world that don't want you to question, and that's a source of great conflict in horrifying ways.

Magic is one of those things that has eluded me my whole life, even though it's a part of my life. Pretty regularly, I'll see a trick that I'm like, I don't know how that happened. And I will spend weeks trying to crack it in my mind. And I think there’s a certain kind of joy in realizing, I might never know, and that's fine. That makes the world far more interesting.

I don't know if you want to talk about depictions in media at all. If that's something -

Pease, let's do it.

I remember there was an Adrian Brody Houdini miniseries where it goes deeply into how he did certain tricks, and the sheer mechanical need to calculate everything. I think didn't pop off as much as it might have, because it featured that. It wasn't a Sherlock Holmes-style fun puzzle. It was a, Oh, he's not really magical kind of revelation.

Of course, there's The Prestige. I have such a strange relationship with that film. I don't find it particularly interesting as a piece depicting magic. I think it's interesting as a mystery that we're watching unfold. It's a movie about murder that happens to take place between two magicians, and Christopher Nolan's love of intricate puzzle making as a style of cinema and writing. But I think something that fascinates me—there's an older character in that movie [played by Michael Caine]. It's a trope I love for some reason, the old man teaching a child tricks, or giving them magic. That's something deeply beautiful for me. I think there's something really gorgeous about: Here are the strange secrets of the world, and now it's your mission to discover how they happen. Like, you're nine years old, and you watch your grandfather pull a quarter out of your ear, and you're like, How? And then you learn how to pull the quarters, and you're like, Well, I can go further with this.

What about The Illusionist—the sort of answer to The Prestige, that came out the same year.

It's also a very fun movie. I really enjoy that film. But what I also found is, once again, it's not really a movie about magic, it's a drama with magicians as the aesthetic. Because it's so much fun, and it's so cool as a filmmaker, to have an excuse to do so many ridiculous effects and tricks, and use it as a narrative propulsion system, rather than a work about the art of magic. There's also Céline and Julie Go Boating, in which one of the characters is a street magician, and they both go on these fantastical adventures together that are surreal, and weird, and sexy, and silly. It's a beautiful movie. It's one of the most gorgeous things I've ever seen. But again, magic isn't the frame of the film. I think it would be tremendously difficult to do a really good movie about magic, about the craft of it, rather than having it as some sort of skin on top.

I think something that's important about magic is - I don't know how to describe this, except that magic is where the comet falls for people. It's the scene in Howl’s Moving Castle where Howl is watching these star people fall from the sky, and one of them becomes him. I think that's what it's like to discover magic for yourself.