A Conversation with Ryan Pollie (Part Two)

Last week, I brought you the first half of my recent interview with LA-based musician and producer Ryan Pollie (who also happens to be one of my best friends). In this week’s second part, we talk through the two LPs Ryan has released under his own name, his ambient projects, our own current collaboration, and so much more…

I feel like there's a real leap in ambition and coherence when you get to the first Ryan Pollie LP. Does that feel fair to you?

Yeah, it was easier to know what I wanted the house to look like once I knew what the land looked like. And it was Jackson Browne, Carole King, Graham Nash, piano, singer-songwriter, acoustics. The types of songs that I wanted to write were less experimental. It was focused. So I could definitely see that there was a maturation in some regard. The bookending choral pieces—it was dressed up. Good for you if you want to wear a polka dot shirt and cargo pants and a top hat, but there's something about seeing someone in a ‘70s outfit with the mustache and the cowboy hat. You’re like, I know what he's trying to say. And I think I knew what I wanted to say, and I knew what I wanted to do, and I did it. And I think that that was not so much my process before that, it was very much, I want to keep exploring through the recording, through the songwriting. And so in earlier records it'd be a classic rock sounding [track], then an experimental synth sounding one, then an orchestra one, and then a carnival one. It was an amalgamation of all the things that I am. But I found this songwriting device, or this mask—I could really play the character well, like an actor finding a role that he was born for.

I never hear musicians talk about getting into character. That's such an interesting concept.

I think when you're wearing the right dress-up stuff, you can transcend it and it doesn't feel like dress up anymore, where you become the character and it becomes an extension of you. Many actors will say that acting, even though they're playing someone else, allows them to access themselves in a way that they can't while wearing their own outfits, or their own masks. You want to be yourself in your art, but this idea of self and identity I think is constructed. And so it's limiting in the sense of, I am this guy, he does this, he likes these things. And Jung would say, Well, what about the shadow self? What about all these things that you're denying because it doesn't fit within your version of who you want to be? I'm not saying that album was my shadow self; I think it was the opposite. I think it was me finding a clear picture of what I wanted to identify with. And it was really important because once I did that, I said OK, I did that. Now it's time to break that.

I was gonna ask a couple other questions and get around to this, but it seems weird to do that. This album is tied up in your experience with cancer. Is that fair to say?

Yeah, definitely.

Is it a cancer album?

In a sense. I had written probably 50% of the material before being diagnosed, and around 50% of the material after being diagnosed, and mixed and released the album either while being sick, or having been cleared of my chemotherapy regimen, but very much feeling sick and recovering. And so the photo on the cover is from before my diagnosis, the artwork is from after. It was really those years, and I think at the time I had this dividing line of like, Well, it's not a cancer record because 50% of the material was before I was diagnosed. But looking back, that was the period of my life when I had cancer. There are even found sounds from the hospital room.

Oh, yeah, there are. God, it's so impactful.

Yeah, I can't listen to it.

I hardly can.

And then the music video for “Aim Slow” was footage of me at the hospital.

It was my life. It was so pervasive that it can’t not be the cancer album. It certainly was what the press grabbed on to—for good reason. And that's complicated to think about. There was a story there, and I think that that always benefits the art when there's a story. But besides the art, I don't know why as a culture, we love that. The idea of someone making a great album is one thing, but the idea of someone making a great album and then dying in a car crash is another thing, and coming to terms with that, reaping the benefits of that, and the attention, is complicated. Do I deserve this? Or do you like it because I was sick? Just a lot of negative self thought around it. Feeling like I took advantage. But I think as you grow as an artist and you continue to have an output, it starts to color in the lines. If that was the only thing I ever did, it'd be one thing. But just growing past it, I can look back with gratitude and pride that I was able to create at such a difficult period for myself.

I spent so much time with that material after that album, playing a ton of shows, different bands. And just playing those songs, and a lot of those songs felt really joyous to do live. We cut the sad ones and just played, like, “Leaving California” and “Getting Clean,” and all the songs that were upbeat and country rock, and that was a blast. So although the recording and the process of making the album was tied up in being sick, I got to spend a lot of time with the material after the period of being sick, when I reemerged, and started playing shows, and had my hair back, and didn't look sick, and was able to divorce that period from being sick. It actually became an album that represented getting better in a lot of ways.

There's a line in there right at the beginning of the album, the repeated line, My God’s insane. That's such an impactful line for me. Is that related to the illness, or is it about other things? I've always heard it as somebody who is processing an unfair hand from fate.

That's definitely what it's about. The first verse [of “Aim Slow”] is about September 11th—this grand loss of innocence, traditionally, in an American myth, is what you'd call it. It was this moment of understanding this concept of fate, and things happening in your life that go against your former experiences of mostly safety. And there's a lot about my childhood—I was dealing with mortality before that, and anxiety, and religious thought from a very young age, challenging these big ideas. But September 11th was the first one that sent a shock through the system in terms of death, and that it could come at any time. It wasn't always dying peacefully in your sleep. There are horrific ways to die. Probably where my plane anxieties formed.

It's not my belief, My god's insane. It rings out to me more as an idea than it does a mission statement or anything, or thesis for what I believe about God. It came to me, and it impacted me, too. But I think it was more related to that first verse as I was writing it. Though I am slow—though I will wear a hard hat in bed when I'm afraid of earthquakes, or I will avoid going on the plane, or I won't go on the road trip. I'll protect myself. Though I take care of myself to not put myself in these positions, something terrible could be around the corner. And that was how I felt with a lot of anxiety. I can't remember—I'd like to say that was written before my diagnosis. And so the idea that something terrible could be around the corner ended up being a bit prophetic. But I think that's something that we're always forced to come to terms with and deal with in different ways. Most likely I'll be okay today, but there's a chance I'm gonna have an aneurysm and drop during this call. These things do happen. And we do kind of get used to the idea that it won't happen to us. And we need to in order to not be scared all the time. But I still have generalized anxiety disorder. I've been struggling with it for a decade or more—my whole life, I don't know. But again, that song speaks to that feeling of fear: Why do I feel like something terrible is gonna happen? [laughing] And then something terrible did happen! But I'm okay.

For the reader’s sake, would you like to give a quick update on the fact that you’re OK?

I always thought, Man, wouldn't it be cool if I was 25 in 1974? Because that's my favorite year for music. But if I was 25 in 1974, I'd have a 7% chance of surviving testicular cancer. And when I was diagnosed, I had something like a 90% chance. So the prognosis was always good, and so many people who flip over the cancer card get some terrible prognosis where they have no shot, and they still go through chemo, and I was surrounded by these people during my treatment. So there was a lot to be grateful for off the bat. And it was terrifying, and the treatment was horrible, and made me feel very sick for a very long time. But I was on the better side of prognosis and the chemo did what it was supposed to and I'm very lucky to say it's been over that five year mark where they use words like cure, and remission, all those good words. So yeah, I still have to get CT scans and blood work done. And every time that I do, I'm like, Oh, this is the day where I get the news that it's back. But I think that's just how our brains work, and how my brain works. I think I'm OK. It's like not listening to your old albums. I don't think about it much. I don't really identify with that person that strongly.

Let's talk about those choral bookends by our very good friend Jason Tsichlis. Where did that idea come from?

Well, I really like choral textures, but I find them to be a bit heavy handed when it comes in contact with popular song. Like, for example, that song we were just talking about, “Aim Slow”—if a choir came in? I just knew that for my own perception. I would be like, Eh, this is a little much.

So you can't hang with the beginning of “You Can't Always Get What You Want”?

I can, but they're the Rolling Stones. I didn't like it for my own material. But I like the idea. I find life and consciousness to be spiritual in the non-religious sense, if that even makes any sense. There is a spirituality to the progression of my thoughts and how I explore consciousness and being alive. And there always has been. I grew up in a religious family, and went to church every Sunday. But to get back to anti-authority, I was very not into it. I was very challenged by it, and didn't find comfort in the church.

I've had people mistake the album for Christian rock, or affirming my faith as a Christian, because the cover has Christian visuals. I'm in a church, and it opens with a choir singing Latin. But I was very sneaky about it. The lyrics that I wanted Jason to compose around—I forget what the actual translation is1, but they were around questioning faith, which is not uncommon within faith. It's not like faith means a blanket I accept. St. Terese frequently questioned her faith. Doubting Thomas, still an apostle. So I wanted it to be religious on the surface, but I wanted the themes of it to be very on the fence, which is how I feel and how I've always felt. It just felt right, also, to have more of a life and death experience than I'd ever been used to, with cancer - to dress that up in a traditional religious concept album.

And what do the titles represent? “Bleomycin” and “Saturn Return”?

So bleomycin is one of the cancer drugs that I had to take in my chemotherapy treatment. It was the toughest one. Your body can only handle it once in the cycle of chemo. And so on Tuesdays, I’d get the bleomycin and it would wreck you. You'd have to take Tylenol Extra Strength every six hours or else you'd get a horrendous fever, and once I forgot to take my dose and I had to go to the ER and put on an IV and it was terrifying. It's a really, really heavy drug.

And the end, “Saturn Return,” refers to me being 29 and getting sick, and this idea that in astrology, Saturn's in the same place as when you were born when you're 29 turning 30, and it's a significant moment in a lot of people's lives. And for me, it ended up being a very, very significant year. And so I'm not deep into astrology, but you see video of what the moon does to our oceans as it revolves around our planet. It is wild what the tides do—it's violent, what the moon does, and if we're whatever percent water, there is something to gravitational pull, where the planets are, what gravity is doing in our system. And there's no denying that, so I'm at least open to these ideas, that your body feels a certain way or does a certain thing, or consciousness is perceived in a certain way while certain planets are doing something. And so yeah, it was a tricky Saturn return, which I think is built into the term. I think it's tricky for a lot of people.

We decided that I should write a folktale to go on the inner sleeve. Do you remember how that came about?

Yeah, oftentimes - I forget what they call it, but in that state in between falling asleep and dreaming, an idea will happen strong enough where it tugs me out. If it's a semi-good idea, I'll drift to sleep. But if it's a strong enough idea, I get up. And I remember getting up and putting that in my notes. I always have a document that I keep throughout making a record, and half of them end up being really important. You kind of say, Okay, well this is gonna go halfway down the document, because these ideas are stronger, I want to make sure they stay at the top. And I remember having an idea and it just going right at the top, being like, This is one that I got to do. Because my life was starting to feel more and more like a tale than it ever had, that I was really learning things from what was happening to me in my life. And so the idea of this kind of mythology or this folklore, telling a story about a guy staring into the face of oblivion and death, was something that I didn't necessarily get across in the lyrical material of the album as a whole. I mean, I did, but I wanted to tell in as many ways as possible, and so coming up with the ideas for the packaging of the album, that was just such a strong idea, having you write this kind of straight to the point story that would help me hammer home my thesis around the record.

And then you have the photo of all your friends inside the vinyl. What was the thinking there?

That was the “done with cancer” party where I felt good enough to have a party at my house and I wouldn't be sick. So many of those people are not even in my close circle anymore but mean the world to me. At that time when you're sick, it's really hard to accept the love. It's really hard to chat on the phone, or even have people over, but knowing that they had my back and were just there - it's really hard to go through stuff alone. I saw yesterday one of my friends who's sick who was like, I really wish I had a partner through this time because it's really hard to be alone. And that just resonated with me so much. I mean, my girlfriend—the poor girl, but she was turned into my caretaker, and that's a really difficult position for a romantic partner, to have to do that in their 20s. And her friends were so kind, and my friends were so kind, and it really felt like we made it through together. And it felt like we were celebrating each other as much as we were celebrating me and that was my way of just being like, Yo, this is not just an album about me. This is about how I couldn't have done this without you guys. That was really important, to show people that it wasn't this solitary, lonely experience about me, myself, and I. I had people with me, helping me, and I couldn't have made an album without those people. Certain people in that picture worked on the record, so literally were giving their time to the actual music. And then also reminding myself that [the music] just an aspect of who I am, and it's not the totality of who I am. That picture shows who I am as much, if not more so, than any song on the album. Those people are who I am.

I’ve got one more really tough question about this album. Get ready.

How does it feel to have written a song as good as “Getting Clean”?

[laugh] I haven't listened to it in a while!

So I will pivot, then. Do you feel that you are able to enjoy the feeling of having written a really great song? Or is that not something you can bask in?

Oh, it's so it's so threatening. Because it never it never feels enough like it came from me. It's like, I'm playing the piano, and I put these chords together, and I'm saying these words, but it's not me and it doesn't feel like mine. It is, but there's always something that blocks me from being able to stand behind a song like that. Because it's always threatening to the other ones. I can do better. It's not that good. What about this one?

Let's move on to the next record. It has a title! It's called Stars. What does that mean?

I got into the idea of this disillusionment I had with LA and what it represented, and the idea of being a star, and the idea of success or fame. I was participating in this rock and roll music that had provided that pathway for so many people now 50 years prior. And I was making similar music to them, but the stardom that came from it was half a century old at this point. And I was feeling like I wasn't getting any sort of fame or validation and was just coming up against a wall. LA is the city of stars, but I was living in LA, participating in music, trying hard, and was just feeling like I wasn't getting anywhere.

I have this book illustrated by Peter Max, who’s one of my favorite illustrators. It's this series that he co-wrote, and they're kind of like picture books with mantras or philosophical thought on one page, and then an illustration on the next, and the bookends of the book are just stars everywhere. And as soon as I looked at that, I was like, I want that to be the gatefold of an album. And I was like, So then the album must be called Stars. It’s a chicken or the egg type of thing where I don't know which came first, but it was clear to me that I wanted to explore this kind of old LA, especially in the music that I was making. It was very Beach Boys orchestrated. That was the first time I was using string sections and horns.

And so it was a love letter to this idea of admitting to myself that I am not in this decade where the music industry is thriving, there's money, there's fame, there's women, there's drugs, there's all this stuff that I thought that I wanted. And it was permission to emulate these heroes from my past in a way that felt like my original voice was as loud as theirs. And I could toy around with style. Someone being like, Hey, this is very Beach Boys, would drive me up a tree at a certain point. I’d say, No, I want to be Ryan. I want to be special. Don't compare me. But it was finally me getting over that hill, and being like, Oh, you you said it sound like the Beach Boys. You listened to the song. Great. Thanks. That was on purpose. And It felt nice to own my influences in a mature way that felt like they weren't informing my own voice but they were things that I wanted to celebrate—certain styles, certain guitarists. And I would give that direction, and that was the first time where I was able to stand behind that instead of being so afraid of sounding like anyone else.

There’s a lot of Vermont imagery in your work. You love Vermont, and you go spend time in Vermont. But what does Vermont mean as a poetic object in your songs?

Often at my moments of highest anxiety in my life, I would go to see my therapist and tell them I just want to get in the car and go to Vermont and leave it all behind and escape. Vermont was home, but it's where we would vacation. So it would mean just that: leaving stresses behind, leaving schoolwork behind, going to the lake. No responsibility. Safety. No earthquakes.

Home is complicated. When you go back home and you're reminded of high school or you're reminded of who you were as a kid, or certain trauma, or whatever it is. But going to a vacation home that you grew up in—there's something about it that frees itself from all those connotations. And not only that, but it's an absolutely beautiful, peaceful place, and it looks very different than Los Angeles. So green. The air smells like you're actually consuming something good for you. You know when Bilbo Baggins says, I just want to find somewhere quiet in the woods to finish my book? That's that place for me, where I sometimes want to leave everything and just be there. During COVID [lockdown] I wanted to move there. I feel safe there like I don't necessarily in LA. And I don't know if we're supposed to feel safe all the time, but I definitely feel safe there. It's part of me, that state

Is there something about Stars that you're particularly proud of that you do not think you could say about LAPD one?

I wanted to do LAPD one myself, and I wanted to express everything the way that I wanted to. And Stars was this ego journey to be like, Hey, I think there's room for collaboration here. I think I want other people to come in and play. I think I want this guy on this guitar solo. I don't know what it's gonna be, but it's gonna be cool. It took me a long time with my art to gain that trust and appreciation for what others had to offer. For a long time, I thought it wasn't going to be right unless I did it myself, and I couldn’t let go of that control. So Stars for me was the graduation ceremony of this idea of the solo artist, and trying to get back into communicating with others in real time, and making music with other people.

Let's talk a little bit about music videos. You have made diverse, varied music videos. So what does the collaboration look like with a filmmaker?

It can be really easy and intuitive, and it can be really stressful. Image and visuals are tricky when you have music, because you're not used to dealing with that. Filmmakers have their own thing they want to express, and music video becomes a medium into which to express that. So the idea of working with an artist and being like, OK music guy, you call all the shots and I'll just stand there with the camera is usually not what you get from a filmmaker who wants to make a music video. They have ideas that they've wanted to accomplish, that they've been thinking about, that's keeping them from falling asleep, and they see a music video as an opportunity to do that in a short form instead of going to make a movie. And so rubbing up against that was always really difficult for me. And there were instances where I'd make music videos and wouldn't be happy with them, or where I was asked to act. Music videos have always been really challenging, actually.

I've done a couple live EPs that are out in the woods. We bring a film crew out there, and we record us doing songs from my album as a band. And those are my favorite film music things that I've done because you watch them play the songs and they're in a pretty place and you hear what you're seeing.

But when I'm driving in a car and I'm on my way to see my girlfriend, lip syncing the song, and then something happens—it just doesn't feel like it fully lines up with the music in the right way. That being said, animation has been a kind [art form]. It seems really intensive for these animators, but it really lines up with the music, because you're not left to just shooting real life stuff. It can be, OK, what's going on in this verse? Let me draw it. And that becomes fulfilling for both the animator and the musician to watch the song come to life.

So that's been a really nice common ground. I've been lucky enough to work with some of my favorite animators that exist. But yeah, I think being in front of the camera is a certain skill set, and it's really difficult for me to perform in that way. So music videos are tough.

How did you get into producing other artists?

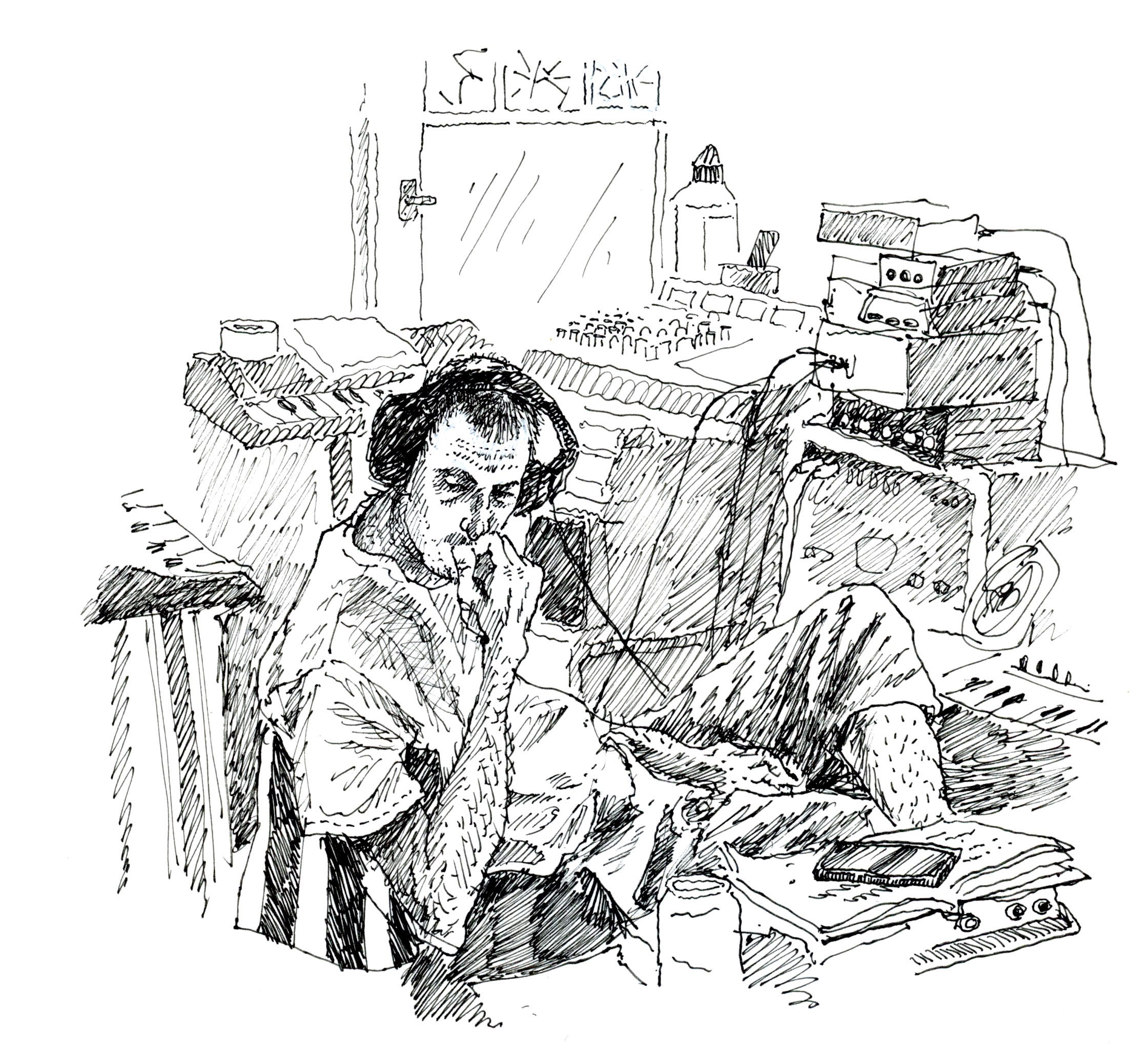

For the first self-titled record, I got a record advance. And the record advance, the first time around, allowed me to work with the producer of my dreams and the mixer of my dreams. And for whatever reason [with the next advance], I decided, Hey, you know what, I'm gonna invest in myself. I'm gonna build a studio, and I'm gonna produce it for myself. And it was a scary decision, but it's what I wanted to do with my life. I love recording. Just the idea of, I'm gonna be this self-sufficient machine where I can have this idea in my head and get to a final product, all in this little Santa’s workshop that I have at my disposal, and I don't need to spend the money or call the people in order to make my dreams a reality. If I'm a painter, I want to have paint, and I want to be able to do it, and have a home studio. So I spent the money for my second record advance building a studio, and invested in myself, and I'm really happy I did that because it provided this path for me to be able to invite others into my home, and say, Hey, this is what I do. If this works for you, I can offer these services. And I think a lot of people look for different things when it comes to recording. Some people want to go into the best studio they can ever get with the huge live room and the treated walls and the top gear. And some people resonate with what I offer, which is, Can we find some middle ground where the gear and equipment is good, and it's vintage, it's old, it's my taste in gear. It's not just the state of the art.

Like, Oh, if you want to make a movie you need to get a Red. It's like, Well, you could make a movie on 16mm and it’d be amazing. But it's a different taste, and maybe you're making something that shot on 16 because it's a period piece from the 70s. Well, a lot of the music that I was making at the time could be thought of in that way. Like I said, Stars was a love letter to a lot of these recording artists that were 50 years old. And I would be searching gear websites—What were these artists using? What microphones? What preamplifiers? What signal chains were they using to get this? Not because I needed to emulate, but I wanted to get closer to that than I could with anything modern that I was hearing. That's essentially what I can offer others: if someone is looking for similar things to what I look for, then it's a no brainer. If you want something that sounds a little older, has older equipment, isn't super high fidelity—isn't, you know, modern rock. If you like old stuff, and you want the cat on your lap, and something that feels like home—because I found that a lot of my studio experiences were like going into surgery without knowing what I was doing. It was not conducive to me expressing myself to be in a place where I felt worried about spilling a drink or dropping a guitar. I think when you want to make art, you need to feel comfortable to express yourself, and you're recording the song, but you're also recording an experience and a memory and a vibe, if you will. And I saw the importance in that and wanted to offer people a space that felt more comfortable for them.

There's this great story of Lou Adler producing Carole King and picking up a lot of her furniture from her living room and bringing it into the studio so that when she got there, she could sit on her couch and there was her lamp and her piano. That just means a lot to certain people. I'm one of those people. Other people go into the best studio in the world and that brings them to a creative place that they couldn't get to in a home studio. But I think a lot of the music that I'm producing is music where they need to feel like they can close their eyes and get to a place and feel really comforted. And I think that the house does that. But because of my recording philosophy, I'm put into a certain bracket where it's hard to compete with the best studios, and that's not what I offer. In terms of recording philosophy, there are different paths to take. And I think a lot of people end up here because it's a philosophy that aligns with them. But I needed to hear that from them. You asked how I got into it—I think I was probably saying, Hey, here's something that I did for me. If that sounds similar to what you’re looking for, come over and let's try it out. And then enough of those situations happened, and I was proud enough of my work, and got better and better, that I started being able to offer that as a service that I could actually stand behind and feel confident about.

What does producing mean?

Great question, because I think it can mean so many different things. It depends on the relationship between the artist and the producer. I've heard stories of producers being what I would think of as traditional engineers who just set up microphones, record a band in a really great way, and that's so important. And then I've heard stories of producers who are more like therapist meets best friend meets guide. I have to be flexible, and not be single-minded as to what my role as a producer is, and saying, Oh, this person needs me to be very hands off? Great. Oh, this person needs me to be very, very hands on? Great. And be ready for that. I think you have to always remember that the art itself, to the artist—the level of importance can't be put into words. And so it takes a certain empathy to sit in that space, and understand it's not just a guitar part. It's not just a microphone. This is very, very important to this person.

I get to watch people bring their ideas to life in my studio, and I get to help them do that with the right equipment, and the right eye. It's like taking a photograph of your favorite place. You can do it on an iPhone, and be like Oh, it doesn't look right. It looks like a shitty iPhone. Or you want the right equipment, you want the right photographer, you want to pay tribute to this beautiful place. And while some people might be like, I want to do it on an iPhone, other people might be like, I want to do it on 35mm, and I want this photographer to do it because he makes it all hazy, and I think that's really important, and it outlines the beautiful landscape, and the colors are very good when this photographer does it. And so you have to have the expertise of how to work with the equipment like a photographer does, but then you want to have the vision and the eye and the care to get this recorded document of these ideas or this place that these people have in their head. And you're always limited by what equipment you have, by what journey you've been on. You only have your perspective. And so I always need to remind myself that it's important for an artist to work with different producers to gain insight. I would never be the producer I am if I hadn't worked with certain producers. And I get to be part of the band. Whether I'm playing an instrument or not, I get to be part of the group, part of the team. Sometimes You have to be a leader. Most of the time you want to be a co-leader with the artist. And the artist having a strong vision or a strong sense of self can be really instrumental in production because then you know what north stars to follow. Whereas if someone comes in and they say, I don't know, you do it, oftentimes you're grasping at what you think they'll like. So when someone's confident and knows what they like, they can go in and be very experimental. But as long as they use their ears and their intuition to know, Oh, I've never heard that instrument before. Play it? Oh, I don't like it. That's really important. So I think you're trying to get the best photograph for the artist, because I don't care if everybody hates it. If the artist loves it, then I've done my job.

You're working on a play right now. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

Yeah, I don't want to say too much, but I've been workshopping it for a little over six months now. Workshopped it at South by Southwest in Austin, and I'm now doing it with a six person band. Right now it's a cast of two, me and this woman who plays the lead person in the play. But it's not dialogue driven. It's mostly dance and music. So the story is told through the songs, and I kind of act. I don't play an instrument live, so I get to express with my body way more than if I was behind a piano or a guitar, and tell the story. I grew up doing musicals, so I know how to gesture, and fill the room more than someone who had just been playing guitar in a band.

I didn't see it coming. But my partner, Grace, who I live with, told me about her musical past in terms of what she's fallen in love with music-wise. And she likes all different kinds of music, but she grew up really attaching herself to musical theater as a kid. And she often says Sondheim was like Disney movies for her, she was integrated into this world of what I consider to be very high art from an early age. ‘Cause Sondheim is not a Disney movie—even Into the Woods is disguised as a fairy tale, but it's about so much more. And don't get me wrong, Disney has a lot of great music, so maybe that's unfair. But she said to me, Hey, I think you're gonna really like this. She came to it with—not an intensity, but an intent to to sit down and really give it a shot. And she was maybe not nervous about it, but I could tell it meant a great deal to her. And this is specifically Sondheim, because she knew that I had done Grease, Oliver!, Fiddler, and loved them. But I wouldn't talk about any of those in the way that I talk about Sondheim now.

When she showed me the [2006] revival of Company - it's hard to compare it to hearing Pink Floyd for the first time, or any of these bands, because it was singular. It was a new experience that I had never had with music before. It was as if someone had translated opera for me and I got to hear what they were saying for the first time. But the music was so much more modern, was so much more American. It was the true American opera, and I was witnessing it for the first time, as if someone had showed you a new testament to the Bible. It was eye opening to this extent of, How did I not know that this existed? And what was so great about it was, it was during COVID, and my best friend and partner was already obsessed, and knew all the words, and knew everything about it. And so I had this resource, and this safe space to flourish in this obsession that was similar to someone showing you the Beatles, but knowing every Beatle song. It was just very fun to be like, Oh my god, I love this one, and her be like, Yes, right?

From there, I think Sunday in the Park with George is the most influential piece on my new album, in the sense that the story of Sunday in the Park with George really resonated with me because it's about an artist who is self absorbed in ways that I have felt with my own art, and how that gets in the way of how you relate with others. And how you can start a partnership with your art, or a friendship, or a relationship with your art that you start ascribing meaning, that transcends a relationship you can have with a human, and you start treating humans as if they can't compare to this relationship you have with your art. And I found that to be something to hide behind, and not connect with people, and run away from connection, and I'm married to my work, that kind of kind of talk. And to watch this man lose what the audience could see as the most meaningful thing you could ever have—love—and to watch him lose that to his work, which eventually was hung at the Chicago Institute, was eventually loved, that just floored me. And so a lot of the themes in my new work are exploring that very thing: this idea that art can cause you to have indecision in terms of your relationships with people and that can lead to loneliness, and regret.

And so it's a story about me and a semi fictional partner, and the strain of being in a relationship and wanting to be an artist and all those things. And getting back to Bilbo Baggins, there's a little bit of representing the woods and the nature in a similar way of being like, I want to be in nature, so I’m gonna run away from humans.

Tell me about The Fridge.

I've done a lot of projects with cassette machines. And my friend Junior Mesa left me a cassette loop to toy around with. The idea here is that you basically have recorded material for a certain amount of seconds. And then the loop is infinite in the cassette. So the tape itself comes back around. And people make loops all the time on their computers, but there was something so early technology sounding about it. To have an amount of seconds that loop instead of an amount of bars, or music at a certain tempo, was so jarring in such a hypnotic way, to hear my piano stop and start again, over and over. And so I would have four tracks on my Tascam cassette machine to make these loops of these instruments interacting with each other and then all starting over again. And the great thing about it was, you would set the intention of saying, I'm going to play this chord and then this chord, and then you'd listen back to it and it was like half of this chord and half of - it would never take the photograph well. It would be like developing a photograph and it's all blurry. You took it of your friend, and you can't even see your friend’s face, but it's still cool, and you like it, and you're like, Believe it or not, that's my friend. I set out to take a picture of them, but now it's a photograph that has all these weird colors in it. I like it in this different way. And so there was this great eye-opening experience to be able to make art that didn't match your intention. And I'd never dealt with that. I'd always been frustrated when something that I was making didn't match what I wanted it to do. But this was about the beauty of that exact concept.

And I fell in love with it, oftentimes then flipping the tape and playing them in reverse, doing very minimal overdubs on top of that, and so it was a very intuitive music making process where I would find myself addicted to it. I would think that my day was over and then start doing a tape loop at midnight and then go to sleep at 3:00, but it would only take three hours to make a piece and that was something I wasn't used to either. I was used to this weight on my shoulders where I'd come up with an idea and say, I'm going to record, and then say, Well, but do I really want to do this for the next six and a half hours? Because I have to add drums, and I have to add this, and I have to add that, and then I have to come up with lyrics. And it just felt like there's a huge undertaking, and ambient music really freed me into intuitive artmaking, and challenged the idea that in order to be good, it has to be hard. And this was a really great experiment in saying, Wow, what I love about this is what the machine did. Isn't that beautiful? It's using me as much as I'm using it to create this thing that is intangible and not what I intended. And I just found that absolutely thrilling, and it was a very singular process on the first record. I'd made it all by myself. On the second record, I made it all by myself and then invited my friend Spencer to come over and play some lap steel on top of it.

It's funny, the week that The Fridge came out, I didn't know what to do to celebrate it. We performed it live a couple times, which was always very difficult, because the idea of that loop not coming where you expect it to. And in response to The Fridge coming out, I decided to celebrate it by making The Fridge 2, which was really cool, and a productive way, to to be like, I don't know what to do with this energy, and then, I guess I'll just make a tribute album to that album. And so it's a natural progression from there.

But I'd never considered the idea of making ambient music not alone, with others, and had no experience with it, but wanted to try. It's like those ideas that you have as an artist that come up—sometimes the train’s moving and you can't get off it, you're like, I guess I'm doing this now. And that's how I feel about the musical that I'm working on. That's how I feel about this ambient collective [Academy of Light]. I can't really say that that was my idea, and I had it at this point, I wanted to do it, and I made it happen. That is what happened, but it felt almost like I was watching it happen. I was witnessing this written thing that was unfolding in front of my eyes.

And so I reached out on Instagram. I said, Hey, as you may know, I have this cool recording studio in my house. I'm going to produce an ambient album of intuitive performance. Who wants to come? And so it started out with people that I knew, people that I had produced, people that I texted. But then it grew into their friends, and it grew into people that hit me up that I'd never met before, who had just followed me. And so it grew and grew until the last session was like 20 people in my house and some people showing up and saying, What is this? And it’s like, Think about it this way: we're gonna play a note for like a half hour and close our eyes and try to enjoy that one note. But of course, you set that intention, and it grows into the whole scale of pretty notes that surround that note, and it's a tone center. It's very modal. And there didn't have to be too much preconceived notion of what I wanted it to be. It kind of just grew into something that I enjoyed listening to and stretching to and meditating to.

There's a certain type of listening that you can do with ambient music that really is different than most other genres. If it's done in a certain way so as to not be over-distracting. It's supposed to pull you in enough where you want to give attention to it, but that you can also give attention to other things without needing to be like, Oh, I'm not paying enough attention to you. I'm sorry. Like, it's okay. I think Brian Eno said that he was in a hospital bed, and his friend put on a record for him but forgot to turn up the volume. And at first he was so frustrated, but then he found it very pleasant, because it was just there. It was just adding something, and he didn't know quite what it was, but it wasn't demanding his attention. It was just over there.

And yeah, hopefully we hit some shade of that. Not in a comparison way, because I think it develops, and it does draw you in more than a lot of ambient music that I listen to. But I think that it is beautiful, and it's also something that can't be recreated. Like, to cover the song would be near impossible, and to recreate it. So it's very much like, Oh, that was that day. And that's really beautiful. And that's how our live performances are, too. Oh, that show is really cool, and it'll never happen again. That ephemeral nature is addictive in art, because I'm used to the recording being an artifact and, and being judged for all of time. Whereas these are a really good combination of effort and effortlessness.

And you're gonna keep it going?

I mean, you know me, I don't like to stay in one place. So we'll see. But I am very much finding it to be something that doesn't take over my artistic output. And it's very fun to engage with, and it's growing in a really natural way. So everything feels overwhelmingly positive around it. And it's really community driven. Now it feels more traditional in the way that people are hearing about it, word of mouth, or hitting me up on my phone to be invited to a show, or to be part of the ensemble. It feels very open-door. And it aligns really well with a lot of philosophies I have around human relationships, too, and not just with art-making but in terms of, We can be friends that see each other when there's a show, and that's okay, and we still love each other. Now we have this community, and certain people in the Academy are playing in each other's bands and hanging out. And it's just this nice little organism that isn't mine.

Let's talk about our project. But I shouldn't be the one to do it. Would you like to tell people what we've been working on?

So we are taking the famous children's stories written and illustrated by Robert McCloskey, and we are creating a musical world for them to live in. And then we are recording narration to go on top of it, similar to what an audiobook would be with music. But we wanted to focus as much of our intention into the music itself, and how the music sounded, and how it told a story, as we did highlight the spoken word. So it was really this opportunity to create this world of music inspired by these amazing books. You wanted to pay tribute to that art by creating art, and your idea was to do that musically. You had this world of music in your head that it kind of sounded like, and you got in touch with me in order to bring that idea to life, and we found an incredible multi-instrumentalist and illustrator named Odin Coleman who really embodies what this music should be and sound like—he plays a lot of fiddle, harmonica. And so it's been this really wonderful, long-form journey. It's like scoring in a certain aspect, but it's also like songwriting. I’ve never done that before. And so it was really fulfilling, and the album is, I think, stunning and is being mixed right now. It'll be the first thing that I've ever released under my own name in collaboration with another person's name. So that'll be really cool, to come out with something with Odin. And hopefully it draws people into this world, leads them to the material that resonated so much with you.

And I'd ask for you to fill in that gap of what I was talking about in terms of why you responded so strongly to these stories by Robert McCloskey.

You're interviewing me now?

Well, just for this part.

So what do I respond to about the work? It is a vision of the world. I've only come to recognize this in a really analytic way as I research more about his place in time, and what he was doing—he was writing during a tumultuous time in history (as though any time in history is not). He was writing between the late 30s and early 60s. And so he is existing against the backdrop of the Cold War, and his books seem to reflect this vision of the world that exists in opposition to that in a subtle way. It’s for kids, it never calls attention to itself as anything like what I'm describing. But then you look at it, and you say, the Cold War is going on, and he created this book that is about the beauty and permanence of nature and our relationship to it. I'm speaking of Time of Wonder, which is my favorite. It is a vision of the world, and it is a vision of existence to an extent, which is this hugely overblown way of saying it.

They are three small stories about his own daughters, and life in Maine, and they are about the smallest things there could be. But they also encompass these visions of the world. Blueberries for Sal is a vision of the world as a fairy tale for a little kid, where you can have a little adventure with a bear and go home safe at the end. One Morning in Maine is a book that is unbearably poignant to me because it's so, so in tune with the headspace of a six year old, which is the age my daughter is. I feel like that book encourages me to be a better parent because it’s so in tune with the interiority of a little kid. And then Time of Wonder is this extraordinary, rhapsodic work that is borderline transcendentalist in its awareness of our relationship to time and nature. And so the books grow in their impact, and each one is so distinct, and we were able to bring that to it.

I think it's the way it grows over the trilogy that really impacted me so much. The way he seems to be writing each book for the kids. Sal is little, so here's a fairy tale about her. Sal is six, here's a story about how God damn serious it is to be a six year old. You're a preteen now, you're receding a little bit from me—he paints them as hazy and fuzzy at that point. And it takes the world more seriously in a deeper way as the kids come into themselves.

It defies words to me a bit, and that is why I felt the need to go to music. Because I want to explain to people what this means to me, and I am trying right now, and it's not quite getting there because words are paltry, and music is deeper. And I just thought if I could connect with you and get these things into your system—I suspected I could probably impress these on you—that you would be able to pull out of my head, through your own head, filter these things through our perspectives, and now through Odin’s—that something extraordinary could come out of it. And sure do I do think it has.

I think that relates to so many things we've talked about. What Vermont means to me, and how that was our vacation home, and where we’d go to as kids, and that safety, and that place that I can go to and hide and feel good about the world and about nature. That's what Maine is in these books. And if the Cold War was going on, it's surely not going on in this place of safety and this little community that they've created for themselves in the woods. And for me as a producer, part of my job is to get inside the artist’s head and understand what they're trying to communicate and what they love about the material. Even though it's performing and writing a lot of it, I wanted to serve you as an artist in a similar way to the way that I serve a songwriter that comes into the studio. I think I said at one point, I don't care who likes it as long as you do. It's not just to impress who you're working with, although I'm sure that has something to do with it. If I can get that feeling, then I've done my job as a producer. And striving to get there, especially through music, as you said, which is this nebulous communication—it's a really fascinating journey to try to get there. And to be like, I think we got that feeling, And you can't prove it, but if you're the producer, and you're working with an artist, and we both feel it, I think we're on the right track.

You say that the spoken word is limited compared to music, but McCloskey is a great example of all these things that on the surface level, and the words, maybe it's a story about a girl and a bear. But for you, these words and these pictures create something so much bigger than that. I get there with movies and music a lot, and now with musicals for Sondheim. But to watch you dive in to this writer and these stories, and see your passion for it—as an artist, I can recognize that in someone. And I wanted to honor that, and dive in there with you. Similar to Grace being like, I'd like for you to watch this Sondheim, you matter to me, and it wasn't clear on the surface at first what it was. But after conversations with you, it was so clear how much this related to you as a parent, and as a person, and how you see the world. And it's almost like we're participating in that tradition and that philosophy, to keep the torch lit.

The lyrics to “Bleomycin” are nitium, sapientiae timor domini, which translates as, the fear of the lord is the beginning of wisdom. The lyrics to “Saturn Return” are ecce ego ipse reproofs efficiar, which translates as, I myself, should become a castaway. ↩