Comin' In From the Mystic Far

“We are here tonight to bring the power and the glory and the LIGHT to your soul.

Hell, that’s why I’m here.

I need it where I can get it.”

- Bruce Springsteen, August 26th, 2023

I was 16 in 2002, the year that Bruce Springsteen released The Rising. I had been an all-consuming fan of the Boss for about three years by then—isn’t 16 just about the peak age for feeling passionate about your favorite artists?—so having any new material from Bruce was a huge event, but this one unusually so: it was his first new record in seven years, since 1995’s mediocre The Ghost of Tom Joad, an album that had come on the heels of the one-two punch of soft disappointments that was 1992’s Human Touch and Lucky Town. Before that had come 1987’s odd, synth-heavy divorce album Tunnel of Love—so, in fact, most significant about The Rising was the fact that it was Bruce’s first album with his legendary E Street Band in almost twenty years, since 1984’s Born in the USA. That latter album was released two years before I was born, and so the gap between full-band albums was something that felt heavy and permanent to me—I had only ever lived in a world devoid of new E Street Band material.

And now we had The Rising, and there was an additional layer of significance: this was being heralded as the first work of popular art responding to the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. Bruce appeared on the cover of Time, with the story promising to tell of “How Bruce Springsteen reached out to 9/11 survivors and turned America’s anguish into art.” Something felt weighty about this moment in cultural history in that way it could only feel at 16—my favorite artist was doing something deep and significant, and I got to watch.

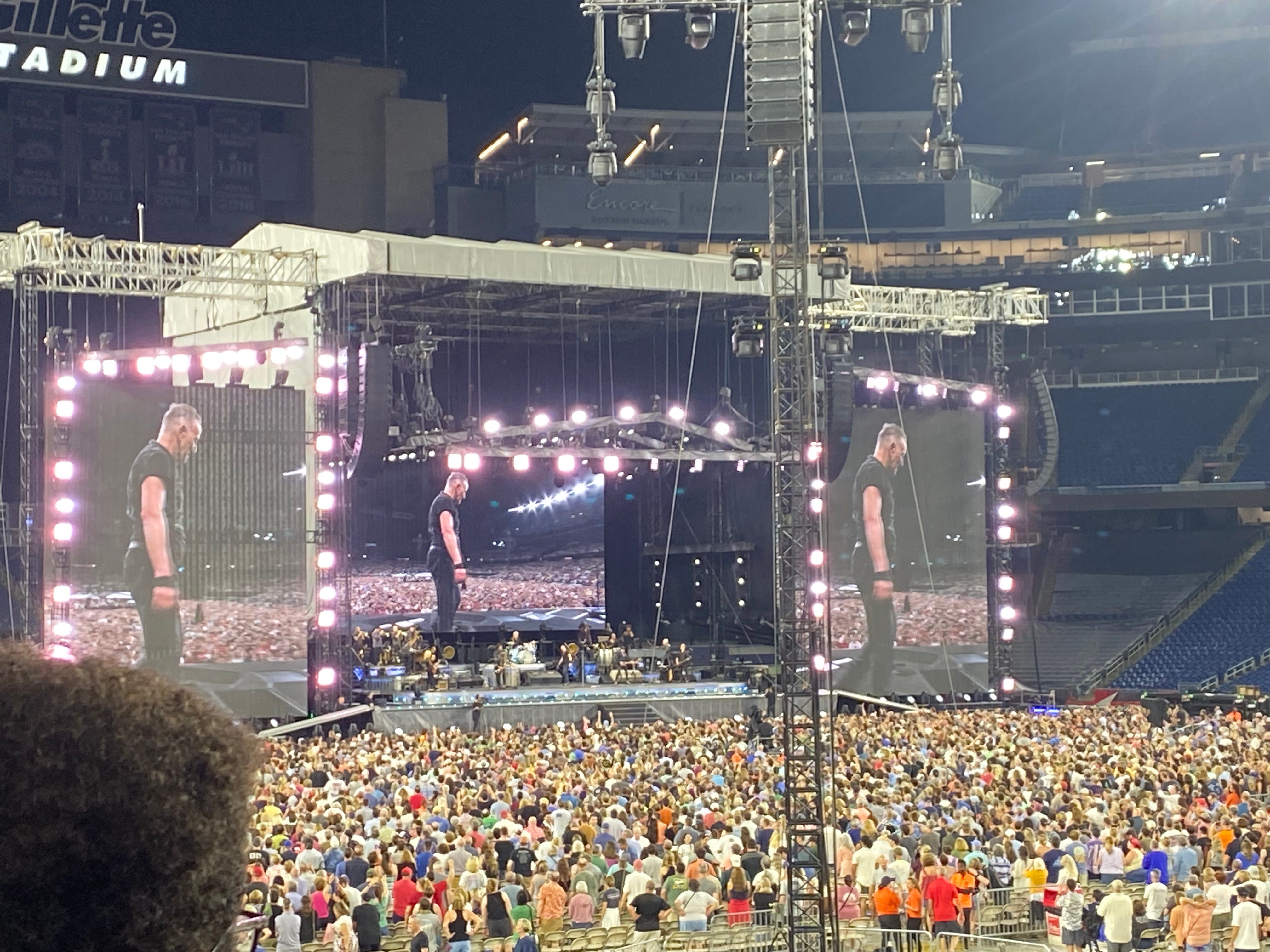

Last night at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, MA, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band opened their set with “Lonesome Day,” the lead track off The Rising. It was an unexpected choice; I’d studied the previous few nights’ set lists prior to making the hour’s drive out to Gillette, and it looked like a pretty standard set—he opens with “No Surrender,” a solid choice. But, for the first time since 2017, he played what must be one of my top five favorite songs of his, and I felt a surge from my heart that spread to encompass my being.

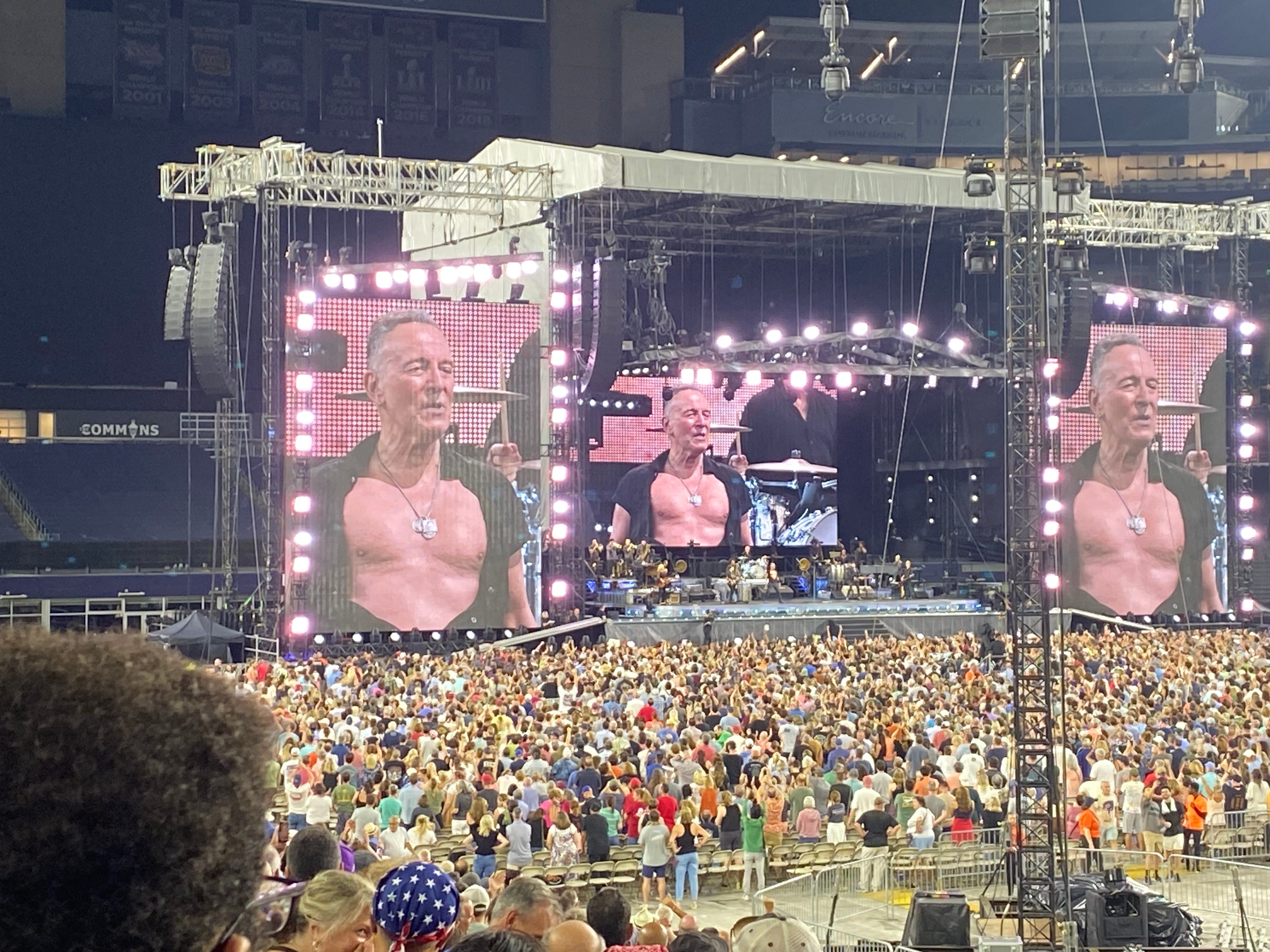

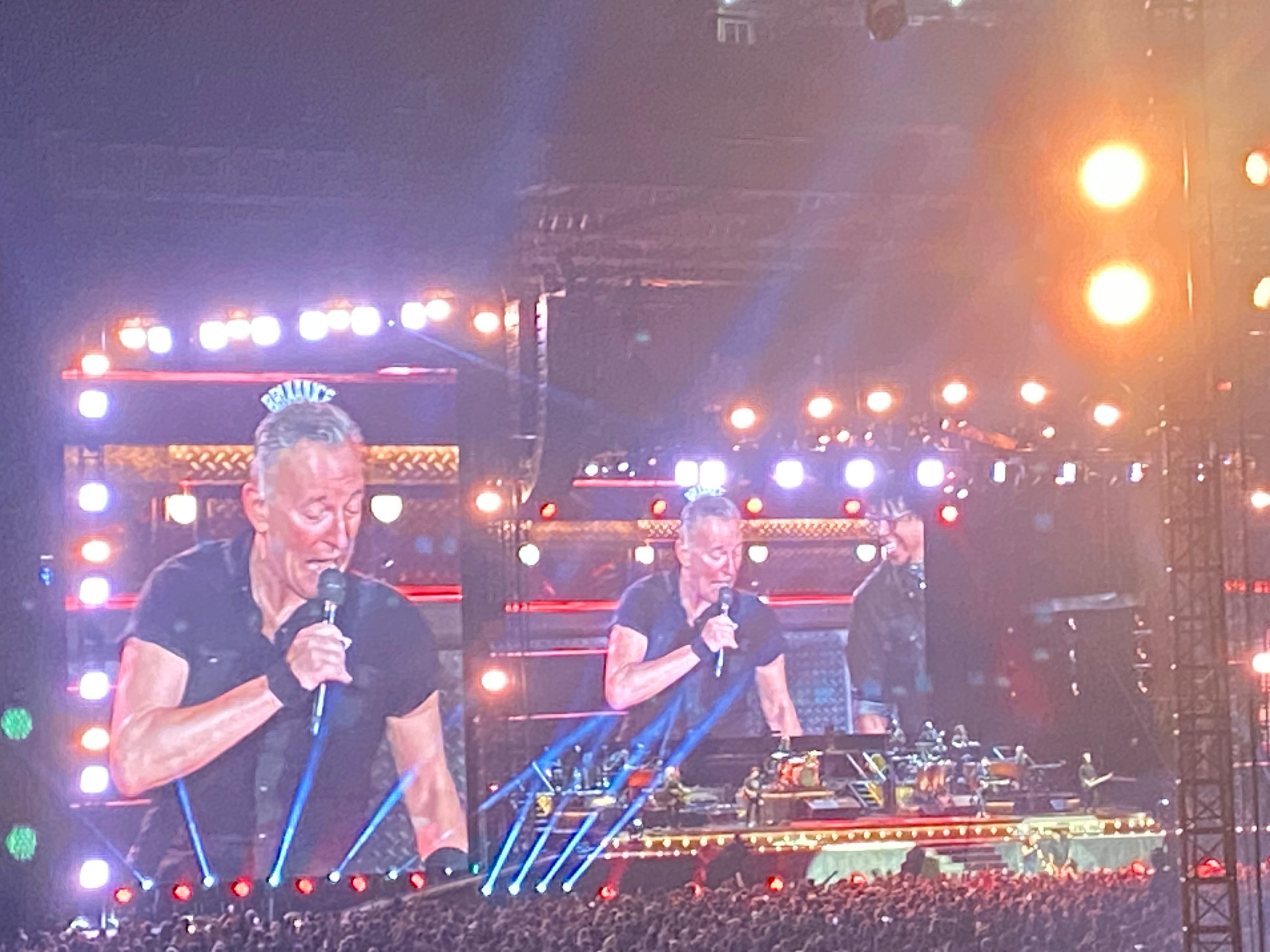

There had been a certain apprehension back in 2002 the first time I slid that CD into the player—what if they’d lost their fastball? But within a few bars, it was clear that we were in good hands. Last night, as it became clear what we were hearing, the feeling was the same. Bruce Springsteen is 73 years old, but he showed up in full force. Whatever he’s doing to keep himself this lean, lithe, and energetic at nearly three-quarters of a century old, the effect is close to miraculous. It’s a little uncanny, to be frank—at the climax of the show, he ripped open his shirt to reveal an enviable physique for a man of any age—but I won’t think too hard about it. For at least one more night, we were blessed to share the world with a Springsteen still at his prime, playing songs he’s played thousands of times and making them feel new and urgent all over again.

I was initiated into the cult of Bruce early in the summer before ninth grade. I was on a cross-country flight, and decided to check out the airline’s prefab playlist of 100 classic rock hits. I was familiar with virtually nothing I heard, and it all struck me as intriguing enough, introducing me to sounds and ideas I’d never experienced. But then along came “Born to Run,” and Bruce Springsteen kicked open the doors of perception. I was hit by that famous wall of sound at full force, and I could feel my mind expanding in real time, the sudden realization that this was possible, and I could probably find more. I spent the flight dutifully listening to 99 other songs, counting down to when “Born to Run” would come back and I could let the wave hit me all over again. That summer was a difficult one for my family, and I took refuge in Bruce, spinning Born to Run and Born in the USA on a loop, studying the foldout lyrics sheets that sat beside me while I painted model cars in the shed. I was a sheltered and shy child, but these songs felt so relevant to me—No retreat, baby. No surrender. It was an anthem not for my daily life but for my generalized adolescent impulse towards a world that felt stacked against one unpopular eighth grader. In these songs, I heard something ecstatic, a truth bigger and deeper than the facts of my day to day.

The themes of Bruce’s songs have shifted with time. Last night’s show leaned heavily on Letter to You, the band’s recent LP focused on aging and death, and an elegiac tone pervaded the evening, with videos of departed bandmates running on the massive screens during the encore. But even a few decades behind Bruce, I feel pulled towards the anthemic arrangements on the album, howling along to his “I’m alive!” on the chorus of “Ghosts.” The song may be concerned with the existential urgency and gratitude of man substantially older than I am, but I still find myself in Bruce’s songs of triumph and defiance.

But I guess we’ll get to that.

This was at least my fourth Bruce Springsteen show; I can’t quite be sure. I first saw him in 2003 at Fenway Park during what it was now clear was a second E Street Band renaissance, and I went home and wrote it up in my journal. “Holy god,” I wrote at eighteen years old on the last night of my summer vacation, “I just gotta say that my brain still just can't handle what I saw tonight—what I experienced tonight more like—and much though I try to think about it all I can really come up with is the feeling that there was a thunderstorm raging inside every last inch of my body.” I like to think my expressive power has strengthened somewhat, but the sentiment applies twenty years later.

I saw him with the band again in college, at the Garden in Boston, and it’s fascinating how comparable the shows are—to an extent, we go to these shows not to be surprised but to attend something more like a revival. Bruce delivers the same show night after night, and he does it with precision and ferocity. At the climax of the encore, in which he roars that we have all just witnessed “the heart-stopping, pants-dropping, house-rocking, earth-quaking, booty-shaking, love-making, legendary E Street Band,” the gentleman behind me could shout the patter alongside the Boss syllable for syllable.

Which is not to say that the night was devoid of surprises. In fact, Bruce leaves substantial room for spontaneity—rather than remain onstage, he spent much of the show at the edge of the floor seats, kissing hands, signing copies of his memoir, and, at one point, handing out a harmonica to an overwhelmed and overjoyed boy of maybe 14—and if that doesn’t make you smile, I’d like to know what would.

My third Springsteen show was in college, too—I returned to the TD Garden for the Devils and Dust tour, a solo outing that climaxed with Bruce at the organ for an ethereal and meditative “Dream Baby Dream” that seemed to stretch on into eternity.

Nothing brought me to quite that sort of high last night. The precision and accuracy of the show means that at least musically, there’s little room for genuine moments of discovery, and even the pounding, howling breakdown at the end of “She’s the One” was restrained compared to the fire-breathing version captured in the 1975 Hammersmith Odeon live recording.

I was stunned by the arrangement of the originally spare and eerie “Johnny 99,” which was reconfigured into a protracted jam that seemed to weave between at least three different styles of rock. But by and large, the thrill came in waiting for each song to begin and realizing what I was about to experience.

If any moment did raise the hair on my arms, it must have been the minutes-long introduction Bruce made to the Letter to You track “Last Man Standing.” He told us about his friend George, who invited Bruce to join his first rock band at 15, an outfit that lasted three years (“Not bad for teenagers,” he noted). Fifty years later, Bruce related, he sat by George’s deathbed and realized that he would now be the band’s last surviving member. And he offered the conclusion he came to that day:

“Death gives you pause to think. It’s like you are standing on the tracks with the white-hot light of an oncoming train bearing down upon you. It brings a certain clarity of thought and of purpose. Death’s final and lasting gift to the living is an expanded vision of the possibilities of this life itself.”

This concert seemed to exist in defiance of nature—again, the man is 73 years old—and so it felt on some level like it was occurring in defiance of death. Even “Atlantic City” and its haunting refrain—Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact. But maybe everything that dies some day comes back—felt charged with a new intensity of feeling. “I can feel the blood shiver in my bones,” Bruce bellowed on the chorus of “Ghosts,” and I felt it, too.

And so I suppose now is as good a time as any to talk about “Wrecking Ball.”

I have a perhaps outsized fondness for Bruce’s 2012 LP Wrecking Ball, and its title track. The album dropped about a year after my first, and still worst, manic episode, one it took me a year to even begin recovering from. And that recovery was initiated by Bruce Springsteen’s “Wrecking Ball.”

On some level, the song is thuddingly literal in its concern with the demolition of Bruce’s beloved Giants Stadium. But on the other, the chorus goes like this:

Bring on your wrecking ball/Bring on your wrecking ball/C’mon and take your best shot/Let me see what you got/Bring on your wrecking ball.

And just like when I was 13 and identifying with the ecstasy of “No Surrender,” I now felt something even more intense for this song about the razing of a Meadowlands arena I’d never visited. Once again I felt myself planting my feet and singing along in defiance of the world and fate, but now biochemistry and genetics as well. C’mon and take your best shot. Let me see what you’ve got. Those words gave me strength, and when I sang them in the shower one day, my wife—who was then still my girlfriend—observed with awe that it was the first time she’d heard me sing in a year.

I didn’t cry when Bruce played “Wrecking Ball” last night. I thought I might, but in my experience, anticipating tears tends to prevent them. Instead, I just listened to the song, and sang it, and tried to live in the moment, and feel the music course through me. I tried, as well, to ignore the screens behind Bruce. It’s always tempting to watch the towering version and see the detail available through the camera’s eye, but I wanted to look at the smaller, three-dimensional man, who looked so tangible and mortal, rather than the icon who’ll likely achieve the closest thing to immortality a rock star can achieve. I tried to savor being there with him. It’s entirely likely that this was the last time I’ll share the same space as Bruce Springsteen, for one reason or the other, so I reminded myself to savor that. For twenty years now, he’s given me words for at least some of the unruly feelings that can really only be channeled when connecting with a favorite song. Everything dies, baby. That’s a fact. But maybe some things last forever, and the sounds I heard last night feel like they just might.