"Funny Pages" Reviewed

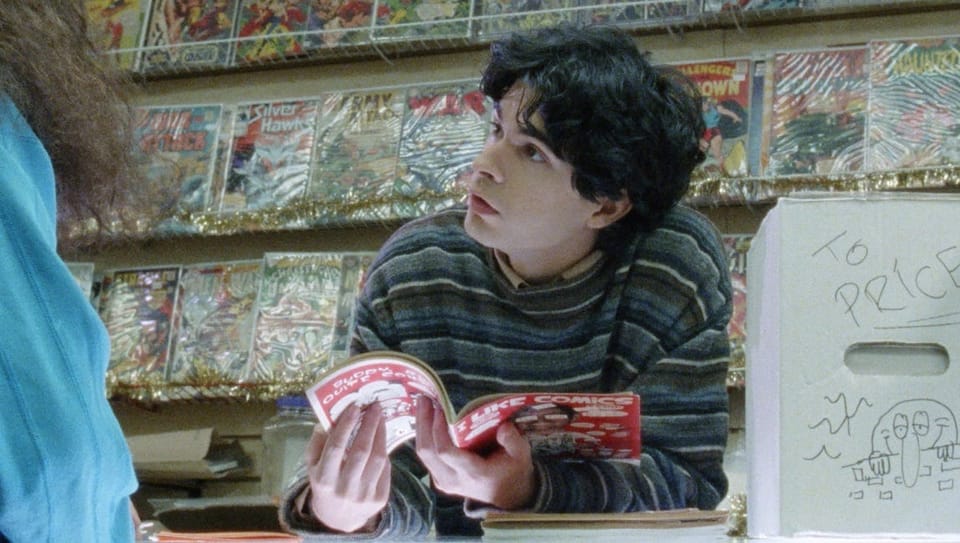

Review: Funny Pages

“Is form more important than soul?” one minor character badgers another towards the end of Owen Klines’s Funny Pages. “Is form more important than soul? Is form more important than soul?” The moment is played for laughs, but it’s a question that would seem relevant to Kline’s debut feature, a film that’s as deliberately loose and baggy as it is filthily soulful.

Though Kline might be best known as a child actor in The Squid and the Whale (as well as the son of Kevin Kline and Phoebe Cates), it’s his interest in what his protagonist calls “old humor comics and undergrounds” that informed this film, which seems to deliberately evoke the grungy (sur)realism of cartoonists like Robert Crumb and Harvey Pekar.

That protagonist is Robert (Daniel Zolghadri), an 18 year old who fancies himself a cartooning prodigy. At the story’s outset, Robert loses his high school art teacher/mentor in truly shocking fashion, and this triggers a chain of shaggy-dog cause and effect that propels him out of his parents’ lavish home in Princeton, NJ and over to the other side of the tracks in Trenton for a Christmastime odyssey including sojourns as tenant of a subterranean apartment that evokes Mad God, typist at the fluorescent purgatory of the local courthouse, and prospective mentee of Wallace (Matthew Maher), an openly unstable alumnus of iconic ‘90s publisher Image Comics. This last thread forms the closest thing the film has to a narrative spine, and there’s an eerie unpredictability to the storyline’s trajectory–Maher is an actor of immense empathy (a quality harnessed effectively in recent years by playwright Annie Baker), leaving even his most startling moments of physical and emotional violence rooted in pathos. It’s tough to envision a happy ending for this prickly pair, but I couldn’t help rooting for them to figure it out.

Watching Funny Pages, it was hard for me to shake comparisons to The Catcher in the Rye, another story of a traumatized young man’s chaotic and selfish efforts to individuate during a dingy eastern seaboard winter. Kline’s film fares remarkably well in comparison to that (eternally controversial) classic; without the benefit of Holden Caulfield’s inner monologue, Zolghadri manages to convey deep wells of wounded narcissism and bitter idealism, leaving room for empathy even while making a string of calamitous choices with easily avoidable consequences. Though the story never descends to quite the depths it might–at no point does Robert seem in much genuine danger, despite the outré situations he entangles himself in–there’s a bracing acidity to its worldview. That worldview is rendered with an appealing lo-fi grunginess that evokes turn-of-the-millennium indies to a grainy T. There’s a perfect sort of imperfection to the precise looseness of form that Kline employs, creating a relaxed yet heightened reality that’s a perfect match for the caricatures Robert has a habit of drawing—”make it really mean,” one character instructs him when commissioning a portrait of a coworker, and Kline seems to turn the same eye on the world: brutally ugly, but all in good fun.

Funny Pages opens tomorrow, August 26, in select theaters and on VOD.

Sundry Ephemera

Last week I finished The Candy House, the latest novel by Jennifer Egan. This one is described as “a sibling novel” to her earlier work A Visit From the Goon Squad, one of my favorite books of the past decade, and so I was eager to get to it, despite these fact that I remember very little of what happens in Goon Squad, having gulped that whole book down in one deliriously happy 2010 day.

The Candy House is not a sequel to Goon Squad; rather, it features many of the same characters and events while shifting perspective to render these happenings from another angle, casting a sidelong view at that story while looking at that story’s sidelong view head-on. It’s a fascinating trick that has me wanting to get back to Goon Squad sooner rather than later, but taken on its own, The Candy House forms a speculative masterpiece (at least for my money) concerning social media and the ways future developments in consciousness-sharing could shape the way we interact with one another and ourselves.

Like A Visit from the Goon Squad, The Candy House traces a daisy chain of protagonists; in some cases, secondary characters in one chapter take center stage in the next, while in other cases we loop back to encompass characters from even earlier while planting the seeds for future strands. On top of that, each chapter is written in a distinct style, from basically standard prose to email epistolary to a sort of lyrical second-person instruction manual. There’s a compulsive pleasure in turning to each new chapter and waiting to see what might be in store, but this is no string of novelties. Rather, the book generates a powerful feeling of interconnectedness, triggering an awareness of the ways minor incidents and actions can ripple out in unimaginable ways, all without becoming some insistent “butterfly effect” narrative. It’s as imaginative and inventive as a book can get, all while leading up to the most plainspoken body-blow of a coda I’ve read in a long time.

Like seemingly all of Twitter, I finished Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal last weekend, and like a good chunk of that viewing audience, I’m still sorting out my feelings on the show. The pilot offered exactly what I would have expected—basically the same tone and tempo as Nathan for You, but exploring this wholly original, cracked notion of creating dress rehearsals for life. I was ready for a season of this, but then Nathan took a hard left turn.

I initially turned off episode 2, which opened with babies being shuttled in and out of the window of a comfortable home in the Pacific Northwest. What is this doing to those kids? I wondered and turned on an Elvis movie instead. By the time I reached the finale, featuring the heartbreaking story of Remy, who wants Nathan to be daddy, it would seem my initial instinct was correct—for all the formal tomfoolery Nathan engages in throughout the series, it resonates for me most as a parent. And it’s not just the idea of children in psychologically stressful situations that made me react powerfully to this show—the notion of time dilation, which saw Nathan go on a business trip and miss ten years of his son’s life, was a genuine gut punch no matter how false the setup. Yeah, I thought, it can kind of feel that way I guess.

In the end, the real happy ending of the show came in episode 3, in which Nathan coached a reticent man through asking for his share of his grandfather’s will despite his brother’s conviction that he’s dating a gold-digger. After a few rounds of rehearsals defending his girlfriend against an implacable loved one, the man abandoned the experiment and took his girlfriend to a carnival, disappearing into the neon dark, hopefully somehow better off for the experience. In the casually nightmarish world of The Rehearsal, that may be about the best you can hope for.

Oh yeah, also…

I love The Rehearsal, but I also love reading the perspectives of people who don’t love it, so I was fascinated by Alan Sepinwall’s extreme distaste for an episode that absolutely worked for me.

I enjoyed my friend Lucy Huber’s clear-headed and probably controversial discussion of the fact that you can be a good parent while not enjoying every single moment.

For the 1987 issue of Bright Wall/Dark Room, I wrote about the Coens’ sophomore masterpiece, Raising Arizona.

For CrimeReads, I wrote about Moonrise Kingdom and its relationship to Badlands, James Dean, and Charles Starkweather.

My new podcast with Ryan Pollie, What a Year!, has dropped five episodes on the art and culture of 2007 so far, and there are five more on the way!

And, finally, my book The Cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson: American Apocrypha now has a release date of April 25, 2023, and preorder links at the Wallflower Press website!