Getting Bizet

There are five little words that Nic Cage uses to summon Cher across a certain transcendent threshold in Moonstruck: "Meet me at the Met."

Cher does, indeed, meet Nic by the fountain outside New York's Metropolitan Opera House, after which they move inside to watch the first half of La bohème. "I like parts of it, but I don't really get it," Cher tells Nic during intermission. But then they're back in their seats, and for whatever reason, there are tears in her eyes, and then there are tears coming down her face. She looks over at him, seeming stunned yet serene, then turns back to the stage, and continues to weep, the tears streaming and falling, streaming and falling.

I found myself thinking of Cher's crying spell a few hours ago while I watched the encore presentation of the Met's simulcast of their new staging of Bizet's Carmen (entirely possibly, as insisted upon by a variety of experts, the world's most beloved opera). But best to get back to all that.

Carmen is based on a novella of the same name by the 19th century French writer Prosper Mérimée, and Mérimée opened his story with a pretty wild epigraph: "Every woman is bitter as bile, but each has two good moments: one in bed, and the other in the grave." The quote comes from the 4th century poet Palladas, and Mérimée presented it in the original Greek. But that choice had a certain effect: men in 19th century France were expected to know Greek via their schooling, while women wouldn't have gotten the privilege. Mérimée inserted a dog whistle of gendered violence into his story, and that thread would continue on to its stage adaptation.

Bizet's Carmen was highly controversial at the time of its premiere. The work was commissioned by the Opéra-Comique, rival to the more refined Opéra. The Opéra-Comique was where you went for pleasant, diverting shows–work for the bourgeoisie. Almost a quarter of all Opéra-Comique tickets were sold to young couples out courting with their parents in tow. But Carmen is a sensual, morally murky, ultimately tragically violent work, and that was just not how they rolled at the Opéra-Comique. It's hard to know just what Bizet was thinking during this time–for unclear reasons, his journals and letters, along with those of his family, were heavily redacted after his death–but later accounts recall Opéra-Comique bigwig Adolphe de Leuven begging Bizet to soften the work.

“An underworld of thieves, Gypsies, cigarette girls–at the Opéra-Comique, the theater of families, of wedding parties?" de Leuven apparently gasped. "No, no, impossible!” He went on to beg (“I pray you”) that Carmen not die: “Death–at the Opéra-Comique! This has never been seen, never!” By all accounts, Bizet and his collaborators assured de Leuven that his concerns would be addressed in full, and then proceeded with their vision as they pleased. M. de Leuven would resign from the Opéra-Comique amidst exactly the controversy he predicted, and Bizet would die believing himself a failure–though he was a prolific hack who churned out commercial work to keep afloat, most of his more ambitious works are regarded as mediocrities. If it weren't for Carmen, we would have forgotten Bizet's name a long time ago, and he died having no idea his opus would go on to be as beloved as it is.

And so, with apologies to de Leuven, we stage and restage Carmen, and the Met's new production is a tough, brutal take on a piece that can otherwise be intensely sensual.

Director Carrie Cracknell has chosen a spare look for this staging, which now takes place not in Spain but rather a seemingly Texan border town. Another notable Met production–the 2009 one directed by Richard Eyre, available to stream–employed dream ballet entr'actes featuring ripped, scantily clad dancers writhing upon one another; here, the entr'actes are sedate shadow plays, hazy and haunting. For another alternative: the 2010 Opéra-Comique revival–also available to stream–was bathed in tones of intense red and orange (with some deep blue when absolutely necessary in Act Three). This production is gray to the core.

There's a dense web of cultural sneering in Carmen. It's a French work about Spain, written at a time when France was pretty thoroughly convinced of itself as the cultural capital of the world (I won't comment on whether that's changed), and thus implicitly superior to the parochial town square of the first act. Meanwhile, a major contingent of the characters are Romani, meaning otherness is a strong concern. Despite being set on the border, and featuring imagery of metal fences and semi-automatic firearms, this production is resolutely free of any ethnic dynamics, which feels like a missed opportunity. (There are still class dynamics at play, as referenced by a violently negative New York Times review–there's not a huge difference between Manhattan audiences enjoying a show about the Texas-Mexico border and 19th century Paris audiences enjoying one about Seville.)

Instead, Cracknell's staging is heavily focused on the idea of gendered violence that's baked into the story going back to the novella's epigraph, and this yields some intensely chilling imagery. I was most struck by a moment just before the climactic murder: José is struggling with Carmen–here at a rodeo rather than a bullfight–when a guard walks past, throwing a suspicious glance their way. All José needs to do is slightly adjust his posture and bearing to seem in control of his emotions, allowing the guard to pass by, no matter how much Carmen continues to thrash.

And then it's over. Carmen is dead, with the murder weapon being not the traditional knife but rather a baseball bat. There's ample chilling imagery in this production–the soldiers of the original are replaced with rifle-toting border patrol, iconography evoking American fascism. In Act Two, as well, there's some of the most dynamic and exciting staging I've ever seen in an opera, as the action is set on a variety of (artificially) speeding vehicles, the lights behind the trucks simulating streaming houses and streetlamps. This sort of staging is what brings me back to the theater, an effect movies just can't touch. With the exception of Shakespearean adaptations, and the extremely rare case like Gus Van Sant's Psycho, movies don't take an old script and throw a new spin on it, and we're all worse off for it. (Imagine a world where we regularly "restaged" Citizen Kane and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Imagine it!) We're also worse off for the increasingly airless approach to the restaging of 20th century theater, which is now consumed by a fidelity to the writer's vision that deprives directors of the ability to get really creative (see the sad case of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, prevented from race-bending by the Albee estate). But I won't spend too long on that particular soapbox.

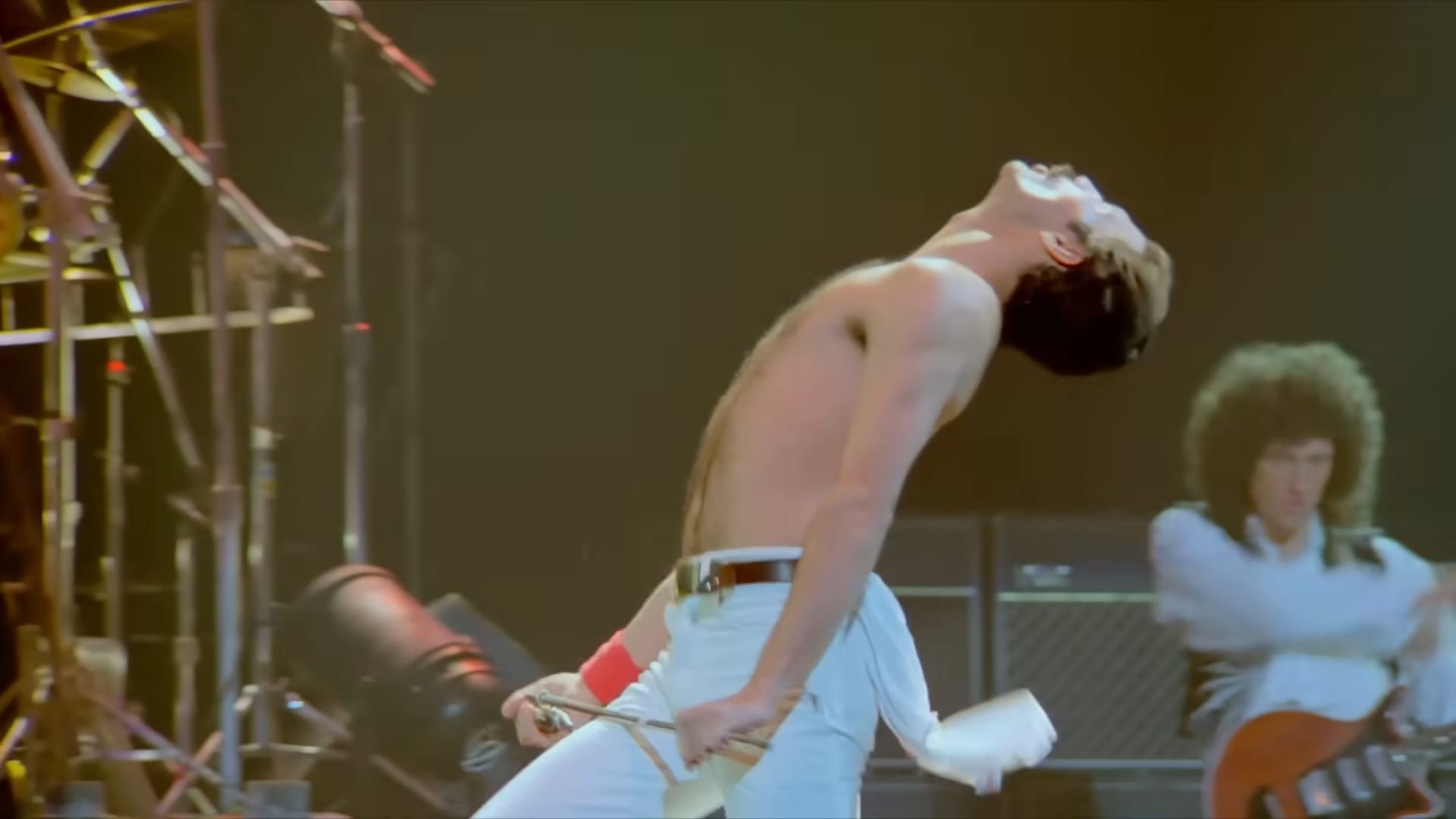

In the past few months, I've found myself increasingly wanting to go to the movies and see things that aren't movies. Maybe it's the pre-Oscars doldrums we're now in; I watched all the good stuff before awards voting last month, so now there's not much to see. And so last weekend, when I really wanted to go to the movies, I found myself perusing the non-movie options. I saw that Carmen was playing, but I missed it by a couple of hours. So, instead, I went to see Queen Rock Montreal on IMAX.

Queen Rock Montreal is a pretty remarkable filmed concert, and seeing it on a very big screen was one of the most pleasurably overwhelming experiences I've had in a long time. During Under Pressure, I was flooded by some pretty intense associations I happen to have with that song, and seeing Freddie put his whole self into the performance only heightened the effect.

But it's nothing compared to what happened to me today towards the end of the first act of Carmen.

A little setup: José has just had his world turned upside down by his first encounter with Carmen. Micaëla, a visitor from home, appears with a letter from José's mother, and when he reads it, he's thrown into a fit of tortured nostalgia. Micaëla coaches him through it, but soon enough, Carmen will reappear, and his fate will be sealed.

This passage–"Parle-moi de ma mère!" as the track is titled–is a little repetitive; José states and restates that he is experiencing intense memories. You get the drift pretty quickly. But isn't that the nice thing about opera? You can just let the emotions of the thing surge over you in waves, the simple feeling amplifying with the repetition and variation of theme.

That said: in this sort of passage, you can also let your mind drift a bit. And my mind did drift. And suddenly, I found myself consumed by my own sort of nostalgic fit. I was caught by memories. And then something kind of remarkable happened: I was suddenly crying pretty hard. The effect continued throughout the remainder of "Parle-moi de ma mère!" I was sniffling relatively loudly in a relatively crowded theater (at least by the standards of a 1:00 Wednesday opera encore). It was relatively embarrassing.

Yet the effect seemed specific to this passage. I found myself testing the effect later–I tried to activate the same memories, but I wasn't moved. On the drive home, I listened to the track a couple of times–I found it lovely, but not impactful. So why be this consumed by emotion during José and Micaëla's interlude?

After all, in her Cambridge University Press book on Carmen, Susan McClary points out that, unlike the idiosyncratic and iconoclastic remainder of the opera, this scene is weighted with "signs of bourgeois sentiment" of exactly the sort with which the Opéra-Comique was previously associated. But there's also a lot going on in this passage! Here, as McClary goes on to write, "harmonic certainty is thrown temporarily in question." José is destabilized musically ("his leading tone f# is harmonized with a B minor triad"–whatever that means) and emotionally. Yet "as they approach the next cadence, they transcend together."

That word "transcend" appears in the paper "Emotions induced by operatic music: Psychophysiological effects of music, plot, and acting: A scientist’s tribute to Maria Callas." In this study, the researchers had a third of their subjects listen to opera, a third of them listen to opera while reading the synopsis, and a third of them watch the opera. The people who just listened to the music experienced pleasure. The ones who listened and read became attuned to the tragic story, and so experienced sadness. But then there's the third group, who experienced neither pleasure nor sadness but a secret third thing: what the researchers termed the transcendent. By experiencing the full effect of an opera–whether in person or via broadcast–you can touch, physiologically, something some people might call divine.

There's another paper, "Emotions During Live Music Performance: Links With Individual Differences in Empathy, Visual Imagery and Mood," which brings in the term "sublimity": this is an inventory of possible opera-viewing experiences that includes "wonder, transcendence, tenderness, nostalgia, and peacefulness." These are all things that happen basically involuntarily, and they're attached to physiological responses like quickened heart rate and slowed breathing–apparently an extremely emotionally heightened state to find yourself in.

Opera is "the best thing there is," Nic insists in Moonstruck. Cher isn't sure she can agree. "It was so awful!" she moans, but then she clarifies. "Beautiful! Sad!" She can't seem to quite process what's happened to her, and I'm struggling to process it, too. Maybe it'll take a little more time and thought. Or maybe it just can't be put into words. The transcendently sublime is pretty famously not explicable. I'll always have the memory of whatever happened to me towards the end of Act One of Carmen today. It wrung me right out. But it's the best thing there is.