"Marcel the Shell With Shoes On" Reviewed

I initially planned to review the new World War II thriller Burial for this newsletter, but in the end that movie generated absolutely no thoughts or feelings for me. So with my review being basically “No comment” (not exactly a sterling recommendation), I decided instead to devote this week to one of next Tuesday’s new streaming options:

Review: Marcel the Shell With Shoes On

At least for this critic, it can be hard to remember a world without Marcel the Shell. This isn’t to say that the original 2011 viral video, a hybrid live-action/stop-motion short which depicted an anthropomorphic shell taking an unseen cameraman through his home and routine, lies unfathomably in the past. Rather, that shell quickly came to seem like a pop culture fact of life, spawning follow-up videos and multiple picture books. So what was it that felt so striking when Marcel first walked into our lives on his titular shoes?

This is the operative question for writers Dean Fleischer-Camp (who also directed), Jenny Slate (who also provided Marcel’s voice), Elisabeth Holm, and Nick Paley, all of whom had to put their heads together in order to bring Marcel from YouTube to the big screen. How to introduce this character to the non-online masses while re-introducing him to those (like me) who vaguely remembered the original shorts, all while expanding his winsome charms to fill the vast bounds of a feature runtime.

To answer the last question first: Marcel the Shell With Shoes On makes the canny choice not to expand the story’s world by much at all. This is a feature film set almost entirely within one house, with the homebound narrative interrupted only by the epic adventure of a local drive. Yet by virtue of the deft cinematography, which places us well within Marcel’s diminutive view of the world, his home comes to feel like a vast landscape of intrigue and peril, be it in the form of an invading squirrel or the ever-present threat of a traumatic spin through the dryer.

The story, such as it is, concerns Marcel’s desire to find his “community,” the lack of which this film posits as among the greatest threats to one’s soul. We meet Marcel through the camera of Dean, with Fleischer-Camp playing a largely-unseen version of himself as a DIY documentarian, and the shell initially lives a life of contented routine with his grandmother (voiced by Isabella Rossellini). He cruises the house, formerly inhabited by a bickering couple but now being rented as an AirBnB (an arrangement that brings Dean into his life) in his rover, a tennis ball fitted with a hole to allow access; he uses a stand mixer and clothesline to harvest oranges from the tree in the yard. But Marcel is haunted by the hazily-remembered loss of his family, and everyone he knew, during the acrimonious split of his home’s former tenants. It’s this loss that motivates Dean to help reunite Marcel with his community of shod shells (and additional anthropomorphic odds and ends), letting some of his own human shell slip in the process to allow in the love of a blissfully naïve mollusk.

It’s this blissful naïveté that accounts for the majority of Marcel’s appeal–Slate plays (and, seemingly, largely improvises) him as a perpetual optimist prone to out-of-the-blue commentary like, “Guess why I smile a lot? Because it’s worth it.” Rather than the saccharine tweeness this quote suggests, though, Fleischer-Camp and his collaborators enliven Marcel with a bracing twist of acid, yielding a character capable of callousness and frustration (“What a sad type of idiot,” Marcel sighs in response to an incessantly barking dog). It’s this awareness of the boundary between cute and too cute that rescues the film from the tweeness trap.

Much like this wrinkle in characterization, it’s the idiosyncrasies of Marcel the Shell With Shoes On that conjure its most affecting effects. While the stop-motion animation is not as rudimentary as that found in the early shorts, the animators maintained the handmade look that lends Marcel a tactile appeal. Without ever calling attention to itself, the camerawork proves quietly miraculous in its ability to capture an elegiac, sun-dappled mood on a pint-sized scale all while supporting the audience’s belief in an inanimate central character. The camera pushes and swoops throughout the environment, but never was I aware of what a difficult trick the filmmakers were pulling off; I was simply immersed in the trick.

What I was less than fully immersed in was the plot. There’s a fine line between simple storytelling and a thin story, and this film walks that line precariously in its tiny shoes. The instinct to keep Marcel’s adventure largely confined was a smart one, but there’s only so much material to be drawn from life with his dotty grandmother, and once the novelty of the conceit wears off, there can be often dispiriting lulls between bursts of narrative momentum. At times, Marcel the Shell With Shoes On feints towards genuine engagement with themes of grief and loss, but for want of a living, breathing protagonist, the effects can struggle to land. If Marcel’s appeal lies in his unstudied innocence–much of the charm of the shorts came in the feeling that Slate was surprising herself with Marcel’s dialogue, and always on the verge of breaking–then the effect can be hard to manufacture, and scripted monologues ruminating on the philosophy of being a shell can ring somewhat hollow.

There’s a pleasing narrative harmony to the realization that all of Marcel’s household innovations are actually workarounds to compensate for his lack of community. It might be a pat lesson, but in a movie that seems designed to appeal to both children and adults, it’s worth imparting. We can get by on our own, but it’s hard to thrive, as much for a human as a one-eyed shell.

Marcel the Shell With Shoes On will be available digitally this Tuesday, September 6th.

Sundry Ephemera

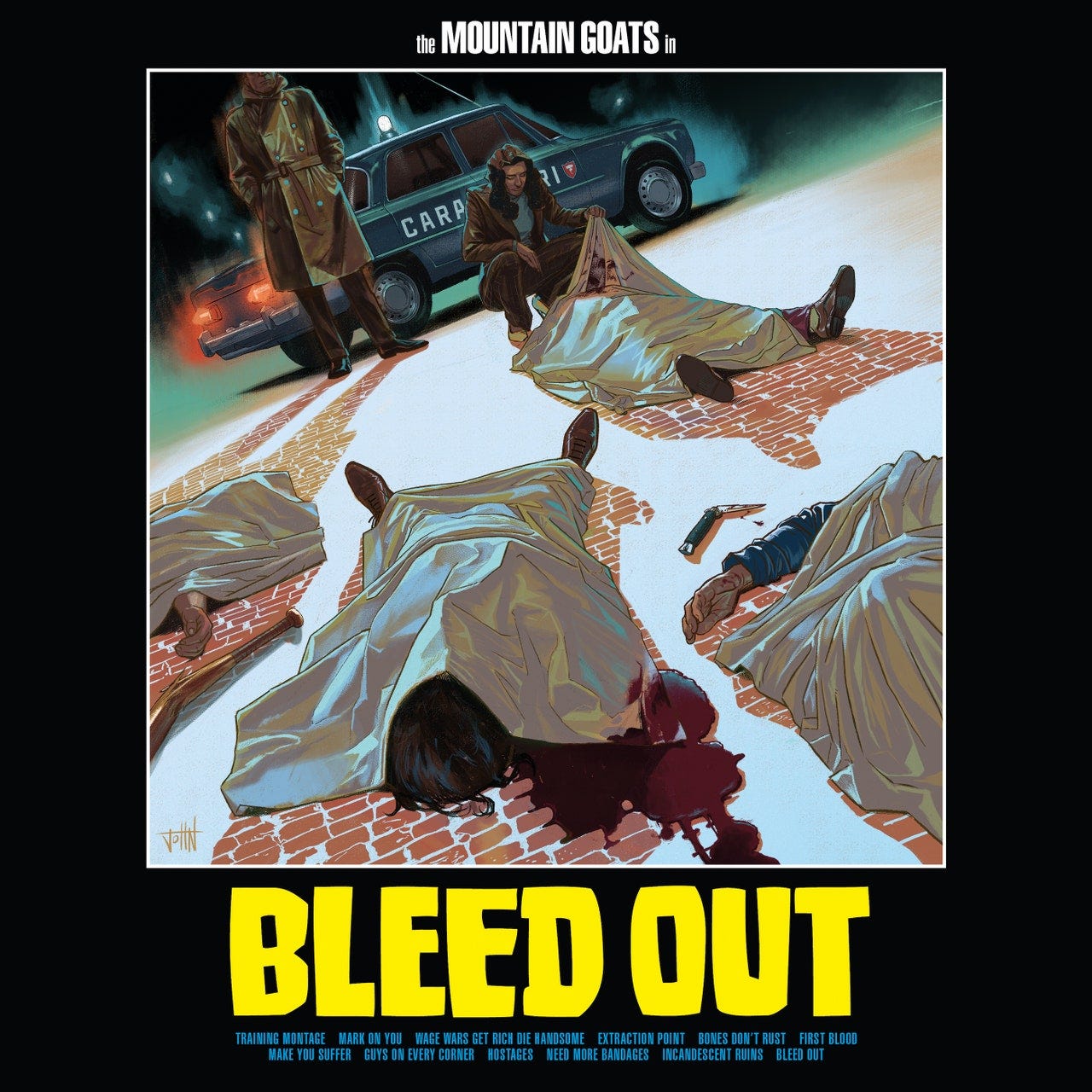

I’ve been spending a lot of time recently with the Mountain Goats’ new album Bleed Out, which band mastermind John Darnielle has been describing as a collection of mini-action movies. The continuous high-concepts of the Mountain Goats are a large part of what drew me to the band–I got on board with The Sunset Tree, Darnielle’s 2005 musical memoir, and I’ve followed him ever since for albums “about” everything from pro wrestling to tabletop role playing games and beyond. The great thing about the Mountain Goats is that if an album doesn’t totally land for you, you won’t have long to wait for the next one (this is the band’s sixth album in five years), but I’m pleased to report this one has struck me like none of their albums have struck me in about a decade.

Darnielle’s lyrics tend to be dense with ideas and imagery, but the music is hardly esoteric–this is a band that knows how to rock, and that’s the primary imperative of Bleed Out. This is an album that rocks consistently, from the adrenalized ecstasy of the opening track, “Training Montage” (a song I’m halfway convinced should be at least on a long list of best Mountain Goats songs) to the grungy hysteria suggested by the title of the third track, “Wage Wars Get Rich Die Handsome.” As for the lyrics, at this point I’ve only processed them enough to get the rough shapes of the album’s motifs–sweat-soaked cityscapes dense with screeching tires and gunfire, primarily–so I appreciated the thoughtful consideration my friend Sarah Welch-Larson has lent those lyrics, which she found to be notably lacking in “the complicating examination” of which Darnielle is capable at his best. Sarah’s point is a sharp one, and maybe one I’ll come around to sharing more as the album settles and my initial thrill wears off. For now, I’ll just keep spinning “Training Montage” until the play count becomes worrying, and then probably keep playing it even longer.

About a month ago, I wrote about finishing the first season of the Apple TV+ series For All Mankind. In the weeks since, my wife and I plowed through seasons two and three, and now we’re facing down a world free of speculative NASA history. It’s a weird, stranded feeling, reaching the end of the road with a TV show, but fortunately this series packs enough narrative density to leave me with plenty to pick over while I wait for a fourth season.

It’s been interesting to see the show continuously walk away from its own formula. Each season so far has picked up about a decade after the last, a pattern they’ve already promised to keep up with season four, and this means the deck is entirely reshuffled not just in terms of the characters’ status quo but the tone of the season’s events. I’ll admit to finding season two almost oppressive at times in its commitment to exploring the psychological fallout of the first season’s events–I admired the swing while not particularly enjoying watching it play out. This is a show that isn’t afraid to punish its characters, and the effects are frequently well-modulated (though one howlingly misjudged story choice involving one catastrophically mismatched sexual pairing should have been put out of its misery between seasons two and three), but I can wonder at times whether that punishment extends to the audience in a way that feels out of step with the diegesis. While season three is likely the most fun to date thanks to the narrative engine of a three-way race to Mars, it ended in shockingly brutal fashion. Only season four will reveal whether that brutality serves the story or exists mainly to gut-punch the viewer. There’s no chance of me abandoning one of my new favorite shows, I just can’t help missing season one and the more generous balance of twisted guts and soaring hearts.

Oh yeah, also…

Now that I’m caught up on For All Mankind, I could finally read Roxana Hadadi and Kathryn VanArendonk tackle the question of where the series goes from here. Their answers make a lot of sense, even when I wish they didn’t.

On the new episode of What a Year!, Ryan and I talked through Animal Collective’s Strawberry Jam and Julie Taymor’s Across the Universe, and then I talked to Hannah Bonner about Maggie Nelson’s poetry collection Something Bright, Then Holes.

Reupping the pre-orders for my book on Paul Thomas Anderson, out next April. You can pre-order basically anywhere, but consider doing the publisher a solid and getting it directly from them.