My Summer of Elvis: Part Two

I’m still on vacation this week, so you won’t find a review of a new release here. Instead, I’m devoting another week to my obsession of the summer: Elvis Presley. Last week, I tackled Baz Luhrmann’s biopic, which I’ve seen six times in the past two months. This week, I’m shifting over to Elvis the man–or, more appropriately, Elvis the media figure. At this point I’m still solidly in the beginning of the second book of Peter Guralnick’s two-volume biography (it’s the thick of the ‘60s, a decade Luhrmann almost entirely elides), so I won’t call myself an expert on every nuance of the guy’s life. What I can say is that I’ve watched as much footage of Elvis performing as I can get my eyes on, much of it multiple times, and I have more thoughts on that footage than anyone probably needs. But for your reading pleasure, I’ve condensed those thoughts into the following essay on what we look at when we look at the king of rock and roll, and why Elvis has never really left the building.

On September 16, 1956, a headline in the New York Times screamed, Lack of Responsibility is Shown by TV. The subject of the article was Elvis Presley’s appearance a week earlier on The Ed Sullivan Show. “Television is in a unique position,” wrote critic Jack Gould. “It has access directly to the home and its wares are free.” Thus, Gould felt discouraged by the “selfish exploitation and commercialized overstimulation of youth’s physical impulses” that TV executives exhibited by putting Elvis onscreen, an act he saw as “a gross national disservice.”

As Gould correctly pointed out, TV was in a remarkable position in the mid-’50s, offering the widespread dissemination of imagemaking in a way never before fathomable. Elvis rode the wave of mass media not just in his recording work but in his onscreen appearances, becoming the first televisual star of his kind, and then traversing both the big and small screen for the ensuing two decades, where the rise and fall of one remarkable act was tracked with at times ruthless precision.

By now, Presley’s variety show appearances are legendary for the hysteria caused by his theatrical gyrations. On the Ed Sullivan Show episode that drew Gould’s ire, Presley’s first appearance on the show, he was largely shot from the waist up, in keeping with a still-mysterious agreement (there are so many contradictory accounts of these negotiations that in her book Understanding Elvis, Susan M. Doll describes the entire affair as “folklore”) meant to suppress the hysteria Presley had caused when appearing in full on The Milton Berle show in April and June of that year.

Presley is cropped at the torso for his Ed Sullivan performances of “Don’t Be Cruel,” “Love Me Tender,” and “Hound Dog,” but when he performs “Ready Teddy,” the camera cuts during the chorus that leads into the instrumental bridge. At last we see, from slightly above, Elvis Presley’s entire body. He sings, “I’m ready, ready, ready to rock and roll,” and then he shifts onto his toes, sliding to the left as though on roller skates. During Scotty Moore’s guitar solo, Elvis ducks his head, bunches his brows, and drops his jaw–we cut back to a waist-up shot just in time to avoid seeing what’s clearly a maniacal shaking of the hips, but the disembodied screams tell us all we need to know. Elvis the Pelvis is at it again.

This is not the only moment that elicits howls of ecstasy. Just as incendiary are Elvis’ other physical and vocal gestures, the ones taking place above the hips. Performing “Don’t Be Cruel,” he injects the space between verse and chorus with an odd, almost bovine Mmmmmm! and pops his brows, causing a brief burst of shrieks. Elvis tries to suppress a grin, shrugs as though acknowledging that this is no big deal and we can move on, but then tosses in another hiccuping vocal tic. The girls fall into hysterics all over again.

It’s easy by now to lean on certain stock concepts when discussing Elvis’ 10 variety show appearances between his TV debut on the Dorsey brothers’ Stage Show in January 1956 and his farewell visit to The Ed Sullivan Show 12 months later. As we all know by now, his purportedly hypersexual behavior single-handedly shattered the glass ceiling for adolescent desire, initiating a generation into a brave new world of hormones and transforming him into a beacon they would follow across the decades, screaming all the way. No matter the fact that his behavior seems downright tame by 21st century standards. You just have to understand, we’re told repeatedly, there had never been anything like it.

I’ve heard this refrain any number of times over the years, and it always bounced right off me. I could intellectually appreciate that the Elvis-on-TV controversy represented a Rubicon for American culture. But it meant nothing to me emotionally, and so the brief glimpses I would catch over the years of a young singer wiggling in black and white failed to elicit any response at all. When I finally sat down this summer to watch these appearances in full, though, I felt something surprising: an honest to goodness emotional response that had little if anything to do with the wiggle.

Instead, it’s Elvis’ playfulness that caught me by the heart—the shuddering, swaggering, spasmodic way he pitches his body around the stage enchanted me. I’m given to understand that young people of 1956 saw raw animal magnetism in these gestures, but I simply see spontaneity, a natural born performer demonstrating the joy he takes in his work, and the consummate ease with which he controls his instrument–not just his voice, and certainly not just his hips, but his entire self. On his final Ed Sullivan Show appearance, he described “Don’t Be Cruel” as “my very biggest record last year,” and then held up his hands in a circle and clarified, “I mean, it was no bigger than the rest of ‘em.” The line was presumably planned, but it nevertheless generates the static electricity of an off-the-cuff crack, and Presley’s effort to suppress a smile at the audience’s laughter indicates a similarly unstudied stage presence.

“Everyone who met [Elvis],” Peter Guralnick writes in Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley, “even for an instant, felt that they were a favored one…It was a rare gift.” I’ve only met Elvis through the veil of a screen, but his gift is transmitted just as effectively that way. I feel favored by this man even across the decades, and that spark is the uniting factor in all his most captivating performances. Yes, sure, Elvis was sexy. But more importantly, Elvis was silly, and that’s what’s kept me coming back this summer, eager for more jolts of spontaneity.

Presley’s variety show era coincided with the beginning of his Hollywood career, a sphere of his output that’s certainly less iconic, but one that’s often in direct conversation with his TV work. In the 31 features he starred in between 1956 and 1969 (churning them out at a rate of three per year between 1964 and 1969), directors attempted repeatedly to capture the Elvis Presley appeal. While the party line on the Elvis feature canon is that they’re a waste of film (“There is no such thing as a good Elvis movie,” Mark Feeney wrote in his 2001 essay ‘Elvis Movies,’ “but there are differing degrees of badness”), the way he was used and misused constitutes a worthy line of inquiry, at least to anyone with enough spare time to devote to movies with such imaginative titles as Girl Happy, The Trouble with Girls, and Girls! Girls! Girls!

If any period of Presley’s film career is looked upon kindly, it would have to be the four features he made between 1956 and 1958, an era that ended when he was drafted into the army. Roughly coinciding with the height of his status as a controversial public figure, these movies attempt to capitalize on his notoriety by most often casting him as a bad boy (the exception being his debut, Love Me Tender; as producers were still unsure of how to use him, he was slotted into the role of petulant younger brother to the true lead, Richard Egan). Elvis’ own idol was James Dean, and this is the template into which he was fitted in these years, even starring in one film, King Creole, originally intended as a Dean vehicle. Elvis acquits himself well as a rebel either with or without a cause, but it’s an odd way of attempting to replicate his appeal. Certainly, he was seen as dangerous in these years, but it wasn’t a scowl or a mean right hook that triggered the riots that followed him. For a theoretically menacing public figure, Elvis was pretty damn wholesome, and building a body of films around some vision of him as a delinquent rather than the ball of joy who captured the nation’s heart seems something of a miscalculation.

There are sparks of the variety show Elvis in Love Me Tender (1956) and Loving You (1957). The former is a post-Civil War drama in which Elvis plays a farmer, but no matter; the producers managed to shoehorn in a few anachronistic musical numbers anyway. Performing at a local fair, and even on his family’s farmhouse porch, he wiggles his shoulders and hips as though beamed in from the present day, one of the only remarkable elements of this otherwise bog-standard drama. The wiggling and swiveling Elvis is present again in Loving You, in which he glides across a restaurant floor to the cheers of a young crowd before cutting loose even more dramatically in a climactic coast-to-coast TV broadcast. Loving You is a clear effort to bottle the Elvis Presley appeal for mass-production, functioning almost as an ersatz biopic–though he plays an orphan who rises to fame basically against his will, the hysteria with which his character, Deke Rivers, is met could not be more clearly drawn from reality–when we see Deke’s beloved car defaced by names and numbers of female admirers, the wink and nudge is clear: Just like in real life. Remember?

His third film, Jailhouse Rock (1957), includes another broadcast, but by now the patented appeal of an Elvis TV appearance is suppressed by the confines of the lavish production number that lent the film its title. The sequence is iconic for a reason, but it does little to comment on the appeal of the televisual Elvis. It’s only half a degree removed from the circumstances that made him an icon (he continues to thrust and wiggle, even as the gestures become more theatrical and less spontaneous) but the incremental shift away from the no-frills performance that made his name would become a pattern. In his last film prior to enlisting, King Creole (1958), generally cited as the peak of his Hollywood career, he plays (what else) a singer, but by now there’s barely any wiggling at all. The musical numbers are a joy to witness, but they fall short in the spontaneity that made Elvis’ name. “Acting skill will probably ruin him,” said David Weisbart, director of Love Me Tender, “because his greatest asset is his natural ability.” Three films later, Weisbart’s words were already proving true.

Returning from the army in 1960, Elvis made one more variety show appearance, this time on a special entitled The Frank Sinatra Timex Show: Welcome Home Elvis. The charming Elvis of four years earlier showed up, though this was very much not Elvis the Pelvis. Dressed now in a suit rather than the loud tweed or plaid jackets he’d worn in the ‘50s, his spontaneity comes through entirely above the waist: singing alongside Sinatra, he drops his head and rolls his neck with abandon, a moment so charming that Luhrmann granted it a slot in the closing montage of Elvis that acts as a summation of his appeal. On the big screen, though, the derogatory definition of “the Elvis movie” was quickly established by G.I. Blues (1960), the first of the frothy comedies that would be his bread and butter for the remainder of the decade.

Though he made two attempts at dramatic acting with Flaming Star (1960) and Wild in the Country (1961), they landed with a thud, and so a template was consecrated with the beachy, bouncy Blue Hawaii (1961): an Elvis movie will be a carefree romp; there will usually be a pretty girl who snubs him only to be won over by his charms; odds are there will be a cartoonish fistfight or two; and the runtime will be threaded with pop numbers that bear little resemblance to the rock on which he earned his fame. This is a string of films described succinctly in a 1970 Memphis Commercial Appeal article as “idiotic movies wherein he has some idiotic role that is only idiotic.”

And yet I find something immensely charming about these supposedly worthless films. Silliness is at the core of the Elvis appeal, and though the lighthearted touch in these movies may be external rather than internal (in no film that I’ve seen is Elvis allowed to relax into a spontaneous moment) they get at the heart of his sweetness in a way the bruised and bruising King Creole doesn’t attempt. Elvis may have been dangerous in the 50s, but from a 21st century vantage, he made family entertainment from the jump. Jack Gould is presumably rolling in his grave at the suggestion I might share Elvis’ titillating variety show performances with my very young children, but casting him in all-ages movies feels appropriate to me. I won’t push back against Mark Feeney’s allegation that Elvis never made a good movie (though King Creole does come close, being directed by Casablanca helmer Michael Curtiz), but he made plenty that are quite a lot of fun. You have the straightforward baubles like It Happened at the World’s Fair (1963), and Viva Las Vegas (1964), deviating little from the formula I outlined above. But then there are the stranger affairs like Follow That Dream (1962), in which his family stakes a claim on a patch of beach off the Florida highway, and in which he plays the most incredulous simpleton this side of his erstwhile acquaintance Forrest Gump, and the gonzo Live a Little, Love a Little (1968), a borderline surreal and surprisingly ribald farce in which he plays a photographer tormented by a supernaturally manipulative flibbertigibbet with whom he falls somewhat inexplicably in love. By now, even the worst of his movies has the inherent production value of being made in the swinging, Technicolor 60s, and so if nothing else, they offer a pleasant escape into a cotton candy land with stakes no higher than whether or not Elvis might get a smooch.

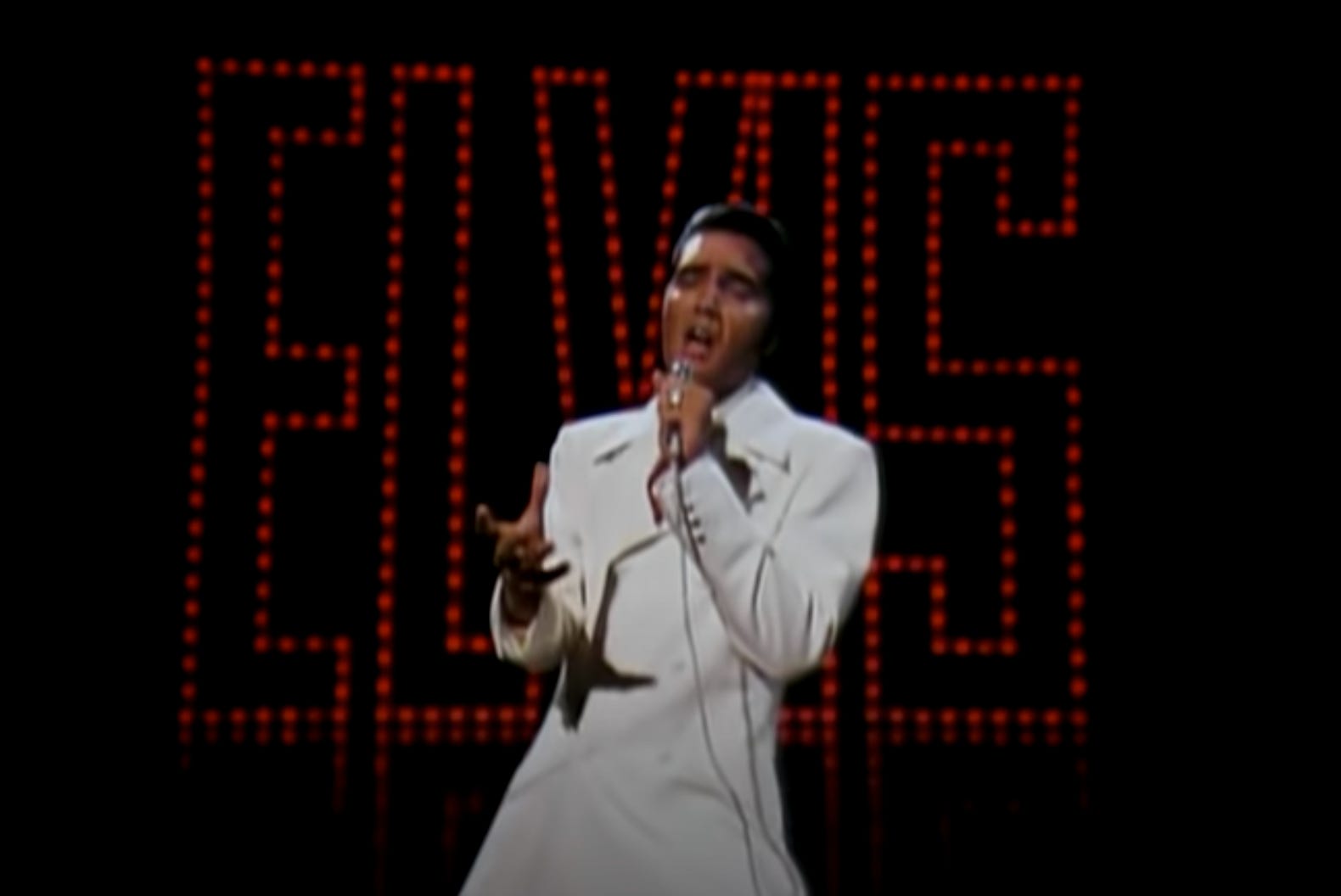

Live a Little, Love a Little–described by Variety as one of his “dimmest vehicles” in which “mediocrity prevails”–was released just over a month before Elvis’ triumphant return to TV in an hourlong 1968 special officially titled Singer Presents…Elvis but known colloquially as “the comeback special.” We couldn’t be further from The Ed Sullivan Show–there are multiple choreographed production numbers, while Elvis performs the balance of the show in the round, a brilliant touch that allows us to observe his connection with the audience rather than simply inferring a relationship via disembodied screams. But a few factors stand out in particular, one hearkening back to the past and one pointing towards the future.

In those segments in the round, we at last see a familiar but long-dormant spontaneous goofiness. For one thing, we see the return of a trademark Elvis gag: the facetious slip of the tongue. Where in 1956 he described “Love Me Tender” as, “My newest RCA Victor escape - release,” now he sings the same song with another calculated error: “You have made my life a wreck - complete!” There’s no particular hip wiggling to be found, perhaps chalked up to the skintight leather suit in which he’s cased, but his physicality in numbers like “Jailhouse Rock” is beautifully unstudied. When repeating the title refrain, he throws his torso around, arm jerking in time, hair flopping madly, a smile never far from his lips. It’s clear that the production team’s primary direction was for Elvis to cut loose at his own discretion, and thank goodness. There’s a reason this hour of television is so central to so many tellings of his story (the HBO documentary Elvis Presley: The Searcher uses it as a framing device, returning to the TV studio between each chapter of his biography). As Greil Marcus wrote of the special, “he put a searing, desperate kind of life into [his] songs…if ever there was music that bleeds, this was it.”

Where the comeback special points the way forward is in the introduction of something new to the Elvis persona: majesty. Finishing “Love Me Tender,” he drops his head and throws his arms into the air. Gone is the goofy kid cutting it up for Milton Berle and Ed Sullivan. In his place is a man making a statement: I am a massive spirit, and I cannot be contained. This is the king of rock and roll ascendant.

Three more ignominious “Elvis movies” followed the comeback special, but his big screen career entered a new, if brief, era in 1970. As Presley prepared for the second year of his residency at the Las Vegas International hotel, a film crew was dispatched to record the proceedings, both rehearsal and performance. The concert footage is incendiary, largely thanks to cinematographer Lucien Ballard, who’d previously worked with Kubrick and Peckinpah, and who shoots Elvis with a lush palette of rich darks and gleaming warmth. But perhaps more notable is the rehearsal footage, which comprises more than a third of the film’s runtime. The focus here is very much on Elvis the cut-up. He clowns for his backing band, and even expresses delight when his microphone stand falls apart on him, never missing a beat in his performance but taking absolute joy in any unplanned incident.

If the comeback special split the difference between spontaneity and majesty, That’s the Way It Is throws the two into the Large Hadron Collider, and the results are spellbinding, even borderline eerie. Elvis is by now decked out in the white bejeweled bodysuit that would become part and parcel with his icon during the last decade of his life, and there’s a distinct parallel between this outfit and the subtly outrageous fashion that was a loud plaid jacket in 1956. So, too, is there a similarity between his clowning on the International stage and his antics for Milton Berle and Ed Sullivan, but seen on a grand scale, his silliness becomes transgressive on a whole new level. This performance looks like nothing so much as a Broadway show, and to see Elvis jam his microphone down his throat, gag, and clutch his neck, or to see him lunge at a member of backing group the Sweet Inspirations, assure her he won’t do it again, and then do it again to her clear dismay, it’s hard not to feel he’s tipped the scale towards the realm of camp. But he infuses his goofball energy with majesty, or else undercuts his majesty with a goofball streak. Perhaps it’s best to say he holds them in a precise suspension–singing “Suspicious Minds,” he injects a quick “Shove it up your nose” in the space between “So if an old friend I know” and “stops by to say hello.” He doesn’t stumble, and throughout the show, he never does.

Greil Marcus found something unseemly about Elvis in this period, describing the message of these shows as: “There is no need to take [it] seriously, no need to take anything seriously.” In Las Vegas and, soon, on the road, Elvis projected a vision of “a throwaway America where nothing [was] at stake.” Yet so, too, did Marcus describe this Elvis as “transcendental,” and seeing the pure physicality on display–his elastic ability to drop to one hip, the other leg jutting straight out–I see a man reaching some sort of peak, even beyond what he attained in the comeback special.

For my money, Elvis’ last theatrical feature, 1972’s Elvis on Tour, represents a distinct valley. Here we watch Elvis travel to fifteen cities in fifteen days, and the king we see is pale and palpably exhausted. This is a man who appears deeply unwell physically and spiritually, and looking at these performances against That’s the Way It Is functions as a study in contrasts. The earlier film reaches a searing high point with “Polk Salad Annie,” which Elvis yowls with all the “mean, vicious” spirit he sings of, punctuating the drumbeats with fiery shadowboxing. Performing the same number on tour, he slurs words he used to spit, his eyes squeezed shut in what appears for all the world to be agony. Rather than singing of a “straight razor totin’ woman,” he sings of a “stray-rare-tone” one. Critical responses to the film generally circled the same idea: “If you want to see lots of Presley onstage,” the Green Bay Press Gazette reported, “it’s good.” The film is something of a landmark for presenting the Elvis who launched a million impersonators, sporting sunglasses as big as his sideburns and a rotation of gleaming capes. But unless the viewer has a serious thing for split-screen photography, Elvis’ theatrical swan song has little to recommend it—the San Francisco Examiner even found it “a rather sad view of the stereotyping of America,” by the end of which “a viewer is depressed with the sameness of it all.”

Elvis Presley’s screen career ended where it began: on television. The last Elvis material to be officially released on home media is Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite, the blockbuster event that provided exactly what it promised: a concert broadcast via satellite to global audiences in January 1973 (viewers in Asia watched live; those in Europe saw it on a delay, while Americans had to wait almost three months thanks to a variety of factors including the conflicting blockbuster event that was the Super Bowl). Given the letdown of Elvis on Tour, I approached Aloha From Hawaii with some trepidation, but I was pleasantly surprised to find a man with his head in the game, one who seemed to appreciate the stakes of this landmark media moment. Where before he was pale, now he sports a glowing tan. He’s certainly trimmer, having dropped 25 pounds prior to the broadcast, though that factor only serves to highlight how free writers were already feeling to fat-shame the man–”his jowls [are] as plump as pork chops,” read the San Francisco Examiner’s review, “[and he] performed more like a fat drayhorse.” But while this is very much not the lithe and strange Elvis of That’s the Way It Is, neither is it the exhausted one of a year before, and when he bellows the closing notes of “What Now, My Love,” the results are nothing if not regal.

If I approached Aloha From Hawaii with a twinge of dread, I felt a knot in my stomach turning to the last filmed Elvis Presley material: the 1977 CBS special Elvis in Concert. Filmed two months prior to Elvis’ death and broadcast two months after it, the special has been suppressed by his estate, apparently due to the risk it posed to image maintenance (at least this is the going theory; Elvis Presley Enterprises has naturally not confirmed any such suspicions). Thus, cueing up a bootleg available on YouTube, I felt uncomfortably like I was preparing to watch a snuff film. What addled and debilitated Elvis was I about to see?

The answer surprised me. In some respects, I did see what I imagined–there is no mistaking the fact that this man’s body is failing him. But what I didn’t plan for is the impish spirit present on his face–not still present, but present once more in a way that hearkens back less to That’s the Way It Is than to the variety shows. As though to underline the comparison, he accompanies his opening number, “See See Rider,” with an attempt at the hip wiggle of old. It doesn’t come off; his days as an agile livewire are long past. But it’s heartening to see him try. “He is almost a grotesque parody of his former self,” read the review in the Lincoln Star of Lincoln, NE, and his “famous Elvis wriggle has been reduced to occasional self-conscious knee spasms.” Well, put me down as disagreeing with the wisdom of the Lincoln Star. At his best, Elvis Presley clearly viewed himself not as a king but as a little stinker, and for reasons I cannot personally account for, that is the spirit that shows its face in Elvis in Concert. It offers a thrill that the theoretically finer Aloha from Hawaii can’t—he never lost it. All my life I’d heard he lost it, and he certainly lost something, but Elvis the rascal was alive until the end. It may be that his personal life, as Greil Marcus put it, “[epitomized] the worst of our culture,” but as a screen icon, Elvis Presley remained a commanding presence, and the results warm my heart in the same way he did performing twenty years earlier.

In her 1984 essay “Sexing Elvis,” feminist writer Sue Wise argued against the notion of cishet men writing the history of Elvis’ appeal, particularly with regards to the significance of his variety show appearances, the era when “he represented their sexual fantasies.” Instead, Wise reflected on her own lifelong relationship with Elvis, a passionate bond that was entirely asexual. “The overwhelming feelings and memories” associated with Elvis in her mind “were of warmth and affection for a very dear friend…Some people who feel alone in an alien world turn to religion or to drink or to football teams to give their lives purpose. I turned to Elvis; and he was always there and he never let me down.”

I am a cishet man, so perhaps I should tread lightly, but Wise’s words resonated for me. This summer, Elvis has provided a safe haven in a world that feels increasingly alien. It’s been odd to discover someone who’s been there the entire time, to remember that this filmed material, which feels so fresh and vital to me, has existed since long before I was born. I wonder if it’s Elvis’ refusal to be timely that makes him feel so urgently current to me. As the dogma goes, there had never been anything like him in the ‘50s, and so he fell into that rarefied realm of people ahead of their time. In the ‘60s, he fell behind the times by virtue of his studious avoidance of cool, making Hollywood fluff while cinematic new waves were rocking the globe. By the ‘70s, he so thoroughly rejected fashionable standards of cool that he brought uncoolness around the bend and established an entirely new category of glory. “He didn’t move through time,” as Eric Wolfson puts it in his 33 ⅓ volume on From Elvis in Memphis, “he existed outside of it.”

If the comeback special represents a gravitational pull in multiple tellings of Elvis’ life story, then the closing number, “If I Can Dream,” represents the gravitational pull within the gravitational pull. Elvis Presley: The Searcher closes by returning to the special and simply playing the song in full, and it’s not hard to see why. There’s a noble ferocity to the number that may not be entirely in keeping with the other high points in his onscreen imagemaking, but that nevertheless epitomizes the purity of spirit he brought to his best performances. Here is a spontaneous Elvis, his arm flailing wildly in a way that indicates he’s entirely lost in the moment, but here is a majestic Elvis, as well, throwing his arms aloft as the camera drifts below him, royalty resplendent.

As I finished outlining this essay, I turned to YouTube, hoping to take another inspirational look at “If I Can Dream,” but instead, I stumbled into an odd subgenre: “If I Can Dream” reaction videos. If you happen to be unaware, a “reaction video” is just what it sounds like–a YouTube personality reacts in real time to something, usually another YouTube video. As the formula goes, the host makes some prediction as to what they’re about to see, we watch them watch it, and then they offer their review and summation. I watched about five “If I Can Dream” reaction videos, though I stopped counting after 20 search results, and I particularly gravitated to those with titles including words like “sorry for getting emotional” and “sorry I cried.” The common factor I discovered was that every host had their expectations upended. Each of them presumed they knew what Elvis was all about: “[From] the little videos I’ve seen about Elvis, I’m expecting [him] to be smiling,” YouTuber _RomeLife said, “having a good time, throwin’ a few dance moves in there.” And then you can watch _RomeLife’s jaw drop progressively as he moves through the video. “I didn’t expect this,” he mutters towards the end, and then he doubles back and watches the last verse again, the one with that soaring key change spurred by the backing choir singing, He can fly. “I’m shocked,” _RomeLife keeps repeating.

I said at the beginning of last week’s newsletter that I couldn’t remember what I knew about Elvis prior to seeing Baz Luhrmann’s biopic, but I know that it largely had to do with a face, a visage frozen in amber. It’s a potent image, but no mere image can distill the appeal of Elvis Presley. Oddly enough given his status as the best-selling recording artist of all time, I don’t think his voice can quite capture it either. To see what made Elvis a myth, a legend, the king, you need to see him in motion. You need to see him smile as he sings, throw in a fake slip-up or two, jam a microphone down his gullet. Elvis Presley was not just a singer; he was an entertainer in the grand tradition, a consummate showman in a way that’s had no equivalent before or since. It took me too long to look up and notice it, but after this summer, I know one thing: for just over two decades, he gave us what may well have been the greatest show on earth.

This newsletter will be back to its regular format next week, I’ll have a review and some sundry ephemera for you. In the meantime, thanks for indulging this little stroll down Elvis Presley Boulevard. He was an indulgent man, and so some indulgent writing seemed appropriate.