"Not Okay" Reviewed

Review: Not Okay

To begin with, it’s worth acknowledging Caroline Calloway’s centrality to Not Okay.

If you’re not aware, Calloway earned that vaguest of titles, influencer, based on a popular (if, allegedly, ghostwritten and astroturfed) Instagram account detailing her life as a millennial in the city. She gained even more attention in 2018 when a planned creativity seminar that Calloway sold for $165 was branded a scam by Kayleigh Donaldson, who tracked and analyzed the lead-up to an event she described as “categorical bullshit.” Calloway, for her part, canceled the seminar and embraced her new title, planning a workshop entitled “The Scam.”

Calloway makes multiple appearances in Not Okay, the second feature written and directed by prolific actress Quinn Shephard. She’s first seen on the phone of protagonist Danni Sanders (Zoey Deutch), who gazes longingly upon a video of this widely reviled pseudo-celebrity; later Calloway will pop up in person as a member of a support group for those who’ve been widely reviled online. In neither case is her name mentioned or her story more than vaguely alluded to. Calloway’s presence is a dog whistle to the extremely online, a wink and a nod to the themes and message of this story. If only it were clearer what those themes and/or message might be.

As we learn during an opening flash-forward (among my most loathed narrative tropes—if you can’t trust your story to hook us with its chronological beginning, might it need a better chronological beginning?), Danni will soon be watching videos that deem her worse than Hitler and even threaten her life. Once we flash back, it doesn’t take long to learn the circumstances that will bring Danni to this point: a photo editor and aspiring writer with a lifelong case of FOMO, she fakes a trip to Paris using carefully doctored Instagram posts, a scheme that falls apart after a terrorist attack on Paris forces her to double down on the lie and shift from playing world traveler to trauma survivor.

So now we have a setup and a presaged payoff, leaving the question of what else this story might have to offer. The answer comes in the form of Danni’s relationship with Rowan (Mia Isaac), teenage survivor of a school shooting whom Danni encounters while doing reconnaissance at a trauma support group. To this point, the film has been a slick, familiar satire of influencers and wannabes, a sort of store-brand version of the weirder, gutsier Ingrid Goes West. Isaac, though, brings Not Okay into a realm of emotional and psychological verisimilitude that’s harder to write off. She’s an immensely charismatic performer, and she almost single-handedly saves Not Okay from itself, drawing out Deutch’s own most empathetic work in a way other costars (notably Dylan O’Brien as an Instagram celebrity so stylized that cartoonish would be an understatement) aren’t allowed to.

On a technical level, Not Okay is thoroughly competent, exuding all the filmmaking finesse of a streaming dramedy. Beyond Isaac’s stellar work, the performers acquit themselves as well as possible within the parameters of the script, and at 100 minutes, it doesn’t overstay its welcome. It’s difficult, though, to say what, exactly, the movie is about—what it means to say, and who it means to be speaking to.

The story would seem geared towards young people, presenting a cautionary tale about the dangers of longing for online notoriety. But the way this message is presented feels out of date—Ingrid Goes West was a full half-decade ago, and this portrait of a world where Instagram is the be-all end-all of social media feels odd in the era of TikTok. Still, even if the central social medium was swapped out, the story’s message would still ring facile. By now, the perils of longing for online celebrity are hardly news, let alone a rich vein for satire. Even stepping away from digital concerns, Danni’s lesson concerning not using others to her own ends feels hardly worth building an R-rated movie around. Not Okay would like to be ruthless, but it most often feels toothless instead.

Coincidentally, the day that this newsletter is published coincides with the airing of a BBC Three documentary on Caroline Calloway entitled My Insta Scammer Friend, so there must still be some interest in rubbernecking this archetype. Maybe Not Okay shouldn’t be written off wholesale. But it’s frustrating to see an actress as appealing as Deutch repeatedly squander her abilities on would-be dark comedies like this, Flower, and Buffaloed, when she anchored one of the most refreshing, frothy comedies in recent years with Set It Up. If only we could see another handful of movies in that vein rather than this one.

Not Okay will be available on Hulu starting tomorrow, July 29.

Sundry Ephemera

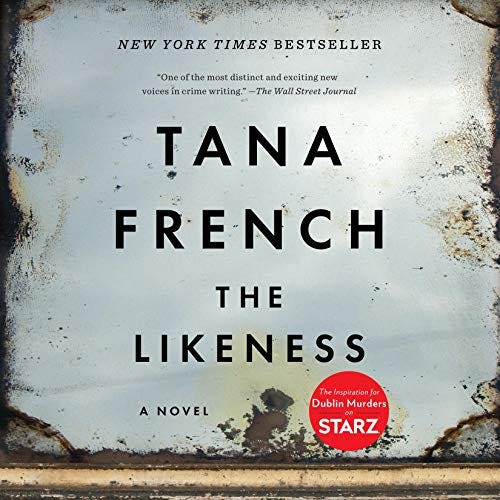

I recently finished Tana French’s The Likeness, the second in her “Dublin Murder Squad” series, which I picked up immediately after finishing the first installment, In the Woods. I tend not to be drawn to crime fiction/murder mysteries/pulp what-have-yous, but French came into my life in 2020 via the excellent The Searcher, and really captured my heart with In the Woods. More than “just” crime fiction, these are lyrical character studies that examine life in modern Ireland with a texture and grace that’s captivating (all the more so given that French is an émigré).

French’s work reminds me a lot of Dennis Lehane, who similarly builds rich worlds peopled with characters worth investing in before introducing a mystery—in the case of most every Lehane book, I’ve forgotten the whodunnit by now while retaining searing memories of character beats. And when I tucked into In the Woods, which tells the story of one case investigated by longtime squad partners Rob and Cassie, I presumed I was getting an Irish version of Lehane’s Kenzie/Gennaro series. I was ready to follow these two through thousands of pages of crime solving. Instead, French introduced a fascinating conceit: it seems that the novels form something of a protagonist daisy-chain–Rob and Cassie anchor the first book, then Cassie anchors the second while introducing new characters, one of whom anchors the third while introducing new characters, one of whom…and so on. It’s a brilliant way to craft a serialized story while ensuring that each book comes to a clear endpoint for the protagonist.

The Likeness has a ridiculously good hook: what if you were called to the scene of a murder only to realize the victim is your doppelgänger? It’s a premise that might seem to invite more of a how-dunnit than a who-, but this isn’t a story of long-lost family, let alone cloning. Instead, the hook serves as a pretense for Cassie to go deeper undercover than would ordinarily seem possible, seamlessly stepping into the life of a murder victim and investigating from inside the eye of the storm. The setting for the majority of the story’s action is a once-lavish manor now inhabited by a clutch of too-close grad students, all of whom guard secrets, and you just know those secrets will come tumbling out in increasingly explosive fashion as the story unfurls.

I won’t say much more except for the fact that, like In the Woods, the denouement isn’t particularly shocking—these are stories with reveals, not twists—all of which underscores the fact that French is primarily concerned with her characters rather than her plotting. She puts her detectives through a special kind of hell of their own making, so that the mystery becomes less, Will they find the killer? and more, How will they make it through this experience intact? I know the second question is a lot more intriguing to me than the first, and I have a feeling I’ll be moving on to the next book in the series before too long, much though it will pain me to bid goodbye to another beloved central character.

Speaking of big twists, I’ve been really enjoying Tim Heidecker’s new album High School, a sweet and sunny bit of soft-rock recently released by one of the most effectively abrasive and bit-committed comic minds we’ve got. Any fan of Heidecker’s—a camp I’ve counted myself among since Tom Goes to the Mayor premiered on Adult Swim in 2004—knows that he specializes in toeing the line between reality and a kind of psychoticomic hyperreality. In recent projects like On Cinema at the Cinema (the long-running and intensely serialized pseudo-review show he hosts alongside Gregg Turkington) and the standup special An Evening With Tim Heidecker (a shockingly committed work of anti-comedy in which he performs as a nightmarish “boundary-pushing” version of himself) Heidecker sees how far he can take his own persona before it breaks, and the answer is “Way further than most people would ever feel like trying” (witness the escalating physical and psychological breakdowns “Tim” has experienced in On Cinema at the Cinema, all without ever acknowledging there’s a distinction between performer and performance).

All of which is to say: it’s kind of startling how gentle and sincere Heidecker’s new album is. High School is something of a concept album, featuring anecdotes seemingly drawn from the singer’s own adolescence—topics include fooling around with girls, mowing lawns, and marveling at the exploits of a burnout acquaintance. There is absolutely nothing cool about this record, from its peerlessly blunt lyrics (“I was living at home with my folks/as you do when you’re fifteen/It was Saturday, I was staying up late…”) to its ‘70s-SoCal production reminiscent of a soft-edged Allman Brothers Band or CSNY. But by abandoning any pretense of edginess, Heidecker expands his eternally-fluctuating persona into a space I never imagined I’d see him reach. There’s a gentle nostalgia at play here that never tips into maudlin yearning, and it all coheres around one perspective in a way that reminded me of a less traumatic version of the Mountain Goats’ The Sunset Tree. I had never been overly tempted to check out Heidecker’s music—there are only so many hours in one life to consume media—but I know I’ll be changing my tune soon enough.

Oh yeah, also…

I really enjoyed Lindsay Zoladz's New York Times profile of Amanda Shires, a country musician I’d never heard of but who immediately captivated me through Zoladz’s rendering.

I also got a real kick out of Roxana Hadadi and Kathryn VanArendonk debriefing the final moments of the pilot for Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal at Vulture, a fine-grain look at a seemingly minor moment that spirals out to become a microcosm for Fielder’s unique relationship to reality.

Bright Wall/Dark Room’s Voyeur issue continued with Catherine Horowitz’s fascinating look at one ignominious moment in Bachelor history that doubles as a fantastic primer on the whole phenomenon surrounding that show.

Closing out the Voyeur issue, Travis Woods went full Travis on David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. It’s a detailed, visceral, and surprisingly whimsical piece of criticism.