Pop!

What follows is an effort by the author to think on the page. It’s being presented here because this is the sort of thing the author has heard at least some readers are interested in. That said, it should not be mistaken for anything like an essay. These are ruminations attempting to move towards a book, and should be read as such.

I have pop stardom on my mind this week. I should have pop stardom on my mind all the time right now—I’m writing a book on Bob Dylan, one of the 20th century’s great pop idols. Dylan was one quarter of that famed Esquire cover that depicted the four major cultural forces of the day: Malcolm X, JFK, Castro, and Bob. He was filmed by Andy Warhol. As a defining pop image of the middle of the 20th century, Bob behind the shades is maybe one step removed from Marilyn in the white dress and Dean in the red coat, but it’s a small step. Yet I forget to think of him as a pop idol, and that’s to my detriment.

Because what is pop? It’s as amorphous a term as “folk,” another word I’m spending time wrestling with by virtue of Bob. Pop has a scholarly definition, I’m sure, and I suppose I should look it and cite it in the book. Yes, I’m sitting here in my office surrounded by books on the topic of pop stardom (Richard Dyer’s classic Star is at arm’s reach, as is my beloved Columbia University Press’s The Star As Icon: Celebrity in the Age of Mass Consumption by Daniel Herwitz; David Gritten’s Fame: Stripping Celebrity Bare is right over there, and Landon Palmer’s Rock Star/Movie Star is right behind me–four books by dudes! Should probably do something about that), but still I wrestle with the idea. Pop is such an expansive, inclusive term—popular art. The art that catches the imagination of the populace. It conjures thoughts of bubblegum, its ephemerality, its proneness to pop. But there’s something so noble about pop, isn’t there? What could be more difficult than achieving the mass acceptance of the populace? Our pop idols—the real ones, the Mount Rushmore of a given generation—exist as something superhuman, and contemplating them as people generates cognitive dissonance that behind-the-scenes documentaries (from Bob’s Dont Look Back to Taylor Swift’s Miss Americana, as I just spent the morning writing about) largely exist to both combat and inflame. Stars as human beings. What could make less sense?

If there’s a Mount Rushmore of 2023, Beyoncé and Taylor are unquestionably on it (and who else is even close?), so I’ve felt compelled this past week to immerse myself a bit in both artists. A chill ran up my spine the other day as I realized I had neglected, as of yet, to put Dylan’s film work of the ‘60s and ‘70s in conversation with the pop star projects of today. Again—I forget Dylan is pop, which allows me to sequester him in the ‘60s, when “folk” and “rock” were things that existed in a distinct form, and sort of no longer do. So I write about the ‘60s and ‘70s, and then move on to another chapter concerning the ‘60s and ‘70s, ignoring Bob’s association to the lineage of pop, a term that’s meant essentially the same thing for the better part of a century.

As I write these words, I’m indulging in a second-screen experience; I’m writing while I watch Beyoncé’s Homecoming (or HΘMΣCΘMING) for the second time this week. I’m doing a little self-directed study as I try and make sense of what’s comparable and what’s unique to every artist, and so this week I’ve consumed Lemonade, Homecoming, Miss Americana, The 1989 World Tour, and Homecoming (again). I’ll likely keep going with Black is King and the remainder of Taylor’s filmography. Earlier this year, I watched about 66% of The Eras Tour; I seemingly missed whatever brief window would have allowed me to see Renaissance. But between those latter two projects, there’s little question that trend-watchers could call this the fall of pop stardom onscreen (only slightly beside the point: even Stop Making Sense and The Last Waltz came back to theaters), and it provides a valuable moment to take stock of how it all intersects with my chosen field of study.

I went to my fourth Bob Dylan concert this fall, cramming myself into a seat at Boston’s Orpheum theater that was seemingly designed for a preteen’s body. I haven’t written about that show here the way I did about the Bruce Springsteen concert I attended in August. Sadly, it wasn’t a hugely inspiring night. There is a vocal contingent of Bob fans who would find this comment to be heresy of the highest order—there were those near me claiming that he sounds as good as he ever did. God bless those people. I don’t go to a Bob Dylan show to hear Bob Dylan’s music or enjoy whatever negligible stagecraft there might be. I just go to be in the same room as a legend—a pop star—while I still have time. I achieved something like a high when I heard him sing “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” though that’s largely because the song lent its name to my book, and I got to ride the surreal bliss of knowing I’m adding my voice to the crowded field of Dylanology. A self-satisfied high, not one really conjured by the music.

I can’t imagine I’ll be going to see a Beyoncé show anytime soon, but Homecoming has captivated me. I’m prone to fascination with concert films, I suppose—about a year ago, I watched The Last Waltz four times in a week. If I did go see her, I’d be going for the music and the stagecraft, so I guess that’s what compels me about Homecoming. That’s the easiest excuse, at least, for why I’m rewatching this movie. But I also know enough to say: there’s something here that isn’t there in The 1989 World Tour (apologies to the directing skills of Jonas Åkerlund). Not all concert films are created equal, and there’s a genuine craft and care to Homecoming that stands far apart from 1989’s quick cutting between a variety of shots within whatever Sydney arena played home to that stop on the tour.

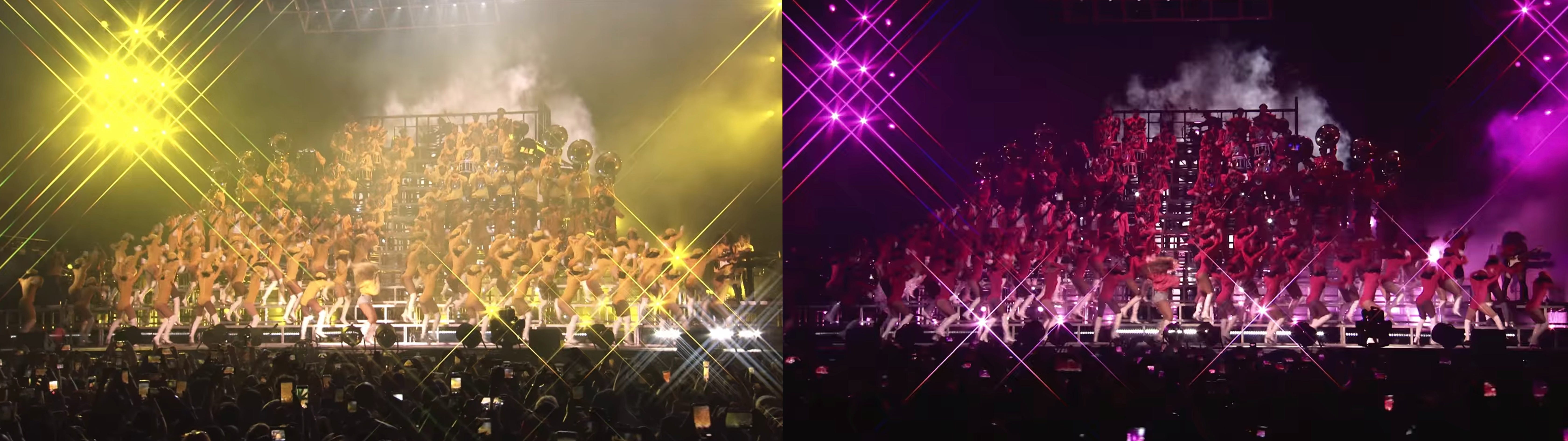

If I were to list movie moments that truly shook me this year, I’d have to point to a match cut in Homecoming. Beyoncé opens the show in a yellow jumper, with her massive backing ensemble similarly decked out in yellow. Then, in the space of a cut, everyone is dressed in identical outfits, but this time pink. The effect is movie magic at its purest, hearkening back to the illusions of Méliès—all that’s happened is a cut from one night to another, but the crowd onstage seems to have supernaturally changed outfits. On today’s watch, I skipped back three or four times just to study the cut and make sure this was editing and not some sort of stage-/witchcraft.

The toggling between the yellow and pink outfits is quietly one of the most intriguing elements of Homecoming, in that we’re having our attention called to the fact that the film was shot across (at least) two nights. I found myself thinking about Eat the Document, Dylan’s experimental pseudo-documentary, which features quite a few onstage performance sequences shot by D.A. Pennebaker that capture Bob and his electric band during their famously tumultuous 1966 world tour. There’s ample cutting between different angles and camera positions in that movie, meaning each sequence must have been shot across more than one night, and likely more than two. But that fact is made invisible to the viewer, a convention of filmmaking—we’re meant to believe something shot across a day or more is happening in real time. Beyoncé allows for the stripping of that illusion, and the highlighting of what’s being crafted. If a movie this cohesive was captured across multiple nights, then what we’re seeing must have been performed with ruthless precision, a breathtaking fact given the number of bodies onstage moving in tandem.

Beyoncé is a much, much better filmmaker than Bob Dylan. His four-hour abstract epic Renaldo and Clara also features a lot of onstage performance, but it’s largely shot from the lip of the platform—occasionally, the camera will stray onto the stage, which becomes very exciting, but it’s a rarity. To see a concert film crafted as a film is an entirely different thing, and for as much as I enjoyed The 1989 World Tour, it just doesn’t feel like a movie on the order of Stop Making Sense or Homecoming, with the latter featuring camerawork that feels considered and deliberate, rather than a flurry-cut, catch-as-catch-can assemblage (am I being rude to Jonas Åkerlund? I definitely am). That said, music video directors aren’t paramount to my interest right now—musicians as auteurs are more so. Taylor has at least become her own director on the small screen (as Patrick Willems said in his hourlong video essay on the topic, she “could potentially be our next major director,” and he wasn’t really kidding), but music videos…well, that’s a whole other topic.

Because I do bump up against a certain problem here: I’m entirely ignorant as to the cultural context surrounding Beyoncé and Taylor Swift. I’m intrigued, but I’m a bit intimidated. That said, I know what it feels like to be captivated by art, and there’s something that feels counterintuitively nourishing about really good pop. The word may conjure images of the disposable, but a lot of my favorite moments this year came from what I’d call pop culture—I think of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem, which looked like nothing I’ve ever seen. Hell, I think of Abbott Elementary’s bog-standard will-they-or-won’t-they story elevated by exceptional writing and performance (“I want to know why you like stuff”). I think of cultural snobs who’d rather not engage with this stuff, ignoring the fact that (God willing civilization lasts that long) we’ll be studying today’s pop culture in half a century. In Murray Lerner’s 1967 Newport documentary Festival, there’s a testimonial from a very, very old lady, who says, “What we call folk now, two or three hundred years ago, possibly, was pop. You see? We change!” And then she smiles so wide. That’s the deal–we’re all living through the stream of pop culture history every day, and it’s better to get with the program before it’s too late to say you were there.