The Between Art and Life Awards

Though I had been looking forward to it for a year, two weeks ago, I elected not to vote in the Boston Society of Film Critics’ annual awards. I had been hit by what I described to the group’s president as “psychological force majeure”—an act of God that prevented me from voting in good conscience. I filled out my “proxy ballot” (a list of my top three picks for each category) so that my friend and colleague Cassidy Olsen could vote in my stead. Looking back a few hours after sending it in, though, I noticed minor errors in some categories that attested to the ballot being completed in an addled state. I couldn’t guarantee any revision I made within 24 hours would be something I could stand by later. Thus, I made the painful decision to simply sit this year out.

I do, however, feel pretty strongly about my top pick in each category! So, in lieu of casting those votes in a closed-door meeting, I’m casting them into the ether, or at least my newsletter subscribers’ brains. And thus, today I present:

The Between Art and Life Awards, or: What I Would Have Voted For If I Could Have Voted.

I’ll present these in the order in which they were voted on by the BSFC, beginning with:

I have not seen Hustle! Or, rather, I fell asleep in front of Hustle earlier this year and subsequently decided I’d seen about enough to render judgment on whether it was worth watching in full. My answer: maybe! But there were a lot of movies this year and sometimes you’ve got to make tough calls. Not finishing Hustle was one of them.

That said, this year I discovered an artist named Dan Deacon, who exploded into my life with soul-saving force (I wrote an entire essay on the topic at Bright Wall/Dark Room this spring). So imagine my delight when I cued up Deacon’s newest film score and found myself not only impressed but absolutely blown away. The Hustle soundtrack became a go-to workout album, a go-to writing album, and generally one of my favorite instrumental albums…maybe ever? This is the easiest call of the year for me. Deacon’s genuinely innovative style is bringing him to the top of the heap as a film composer, and while I’m not sure how he’ll beat Hustle, I can’t wait to hear him try.

I’ve seen more than one Elvis skeptic criticize the film for the sheer overwhelming muchness of it–video essayist Patrick Willems described the film on Letterboxd as “the world’s first two and a half hour movie trailer.” And hey, man, fair enough! It sure did work for me, though, and the sustained high wire act of crafting a feature-length montage—whether you enjoyed the effect or not—strikes me as worth recognizing and celebrating.

Elvis rides a rhythm all its own, blasting through Presley’s life story while cutting corners left and right (what happened to the 60s? Oh never mind…) but those elisions feel purposeful and deliberate. For all intents and purposes we skip Elvis’s rise to fame, but I, at least, feel I experienced everything worth experiencing in little flourishes like a roulette wheel coming to encompass Elvis’s face before morphing into a hubcap—or a ferris wheel becoming a record, which then becomes another record. Is it a shortcut, or a breezy abridgment? Is there a difference? Does it matter?

There was a lot of great editing this year. And then there was one movie that was made of editing (I mean, every movie is, but…you know what I mean). Plus, I had to give my beloved Elvis something, and this was all I could do in good conscience. (Apologies to the Col. Tom Parker faithful, but no, Tom Hanks will not be making an appearance once we make it to Supporting Actor.)

I can’t quite explain it, but something about the shooting of The Northman has cemented it in my brain as a remarkable achievement in a way the writing, acting, directing, and any other element couldn’t touch. In particular, it was the early shot—occurring just over a minute into the runtime, in fact—in which the camera cruises across the freezing ocean towards the cliffside keep of Amleth’s father that made me sit up and think, Robert Eggers and I are just absolutely on the same page.

To be honest, The Northman has fallen a bit in my esteem over the course of the year. It’s still one of my favorites of 2022, but it’s no longer one of my favorite movies the way I believed it was during my first watch (and the way Eggers’s previous film, The Lighthouse, remains). The image-making in this movie, though, is beyond reproach, at least for my money. Each shot feels adapted from some ancient illustration found in some collection of Norse myths—which, of course, they essentially were.

Cinematography is about way more than cool images. But sometimes, if a movie is wall-to-wall cool images, you gotta say it’s got good cinematography. So yeah, The Northman has pretty damn good cinematography.

It’s been pretty disappointing to watch Wendell & Wild—the new stop-motion picture from Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline maestro Henry Selick—slip under the radar and then seemingly sink like a stone. Blame Netflix for doing absolutely nothing to raise awareness (presumably too focused on their other, far less interesting, stop-motion movie of the season). But when you have one of the most exciting technicians ever to work in the medium combining his talents with the mind of Jordan Peele, you’ve got an extraordinarily cool movie on your hands. Too bad so few people were seemingly interested in having it on their hands.

Wendell & Wild tells the story of…well, what exactly? A pair of demons (played by erstwhile comedy partners Key and Peele) who use magical hair cream to raise the dead? A traumatized girl trying to come to grips with what she perceived to be her role in her parents’ death? A joy-buzzer satire of the prison industrial complex? All of the above and more, certainly. I was rarely entirely sure what I was looking at when I watched this movie, but I was sure of one thing: I didn’t want to be looking at anything else.

Fire of Love has hung with me since January, when I watched it as part of the Sundance virtual lineup. I cued it back up immediately upon its Disney+ release (part of the mouse house’s deal with National Geographic) and I was immediately enchanted all over again. This is more than just the biography of Katia and Maurice Krafft, among the world’s preeminent, and probably most famous, volcanologists. It’s more than a re-assemblage of some of the most extraordinary footage of the natural world you’ll ever see. It’s more than a true love story. Through the use of innovative animation techniques and dazed-sounding voiceover from Miranda July, the entire project attains a kind of transcendent poetry that finds some intersection of the awe-inspiring power of the elements and the awe-inspiring power of the human heart.

Katia and Maurice are an unconventional pair, but the movie makes a compelling case that they were brought together by fate, and that their marriage had a purpose greater than just their own companionship. But it makes the case, as well, that companionship in a lonely, volatile world is maybe the best any of us can really hope for. Fire of Love got a lot of great buzz out of Sundance, but it doesn’t seem to have landed with much impact now that it’s available at home. It deserves your attention.

If Fire of Love has hung with me since this year’s Sundance, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair has hung with me since last year’s, and it will keep hanging with me for a long time to come. I don’t remember the last time I watched a film and thought, I am watching something genuinely new—I’ve seen the strange and unusual, but to find something that felt like it was inventing its own language, you have to go back maybe two decades.

And then there’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, a movie that feels like it deserves to kick off some kind of new wave for the extremely online generation. If you haven’t seen the film—well, please do, for one thing. But for another, the way Schoenbrun acknowledges the power of the internet to cleave us in two, separating the physical self from the spiritual one by placing the latter in its own non-physical sphere and leaving the three-dimensional vessel feeling somehow hollowed out…what a concept.

And Schoenbrun pulls it all off with a deftness of tone and mood that suggests a master in waiting—or, maybe, one who’s emerged fully formed. I can’t wait to find out via their upcoming projects.

When was the last time a movie felt like Tár? It’s long, but it’s breezy. It’s staid, but it’s bizarre. It’s full of pops of mystery (the screams) and cracked humor (do I even need to mention the last shot?). Rather than balancing tones, Field manages to encompass all tones simultaneously, or at least flips back and forth between them so efficiently and effectively that following the fluctuating mood is as pleasurable as following a melody.

I knew Tár was special immediately, but it wasn’t until the last act that I fully recognized how unusual it is. Once the script starts leapfrogging across time, a fracturing of the story that syncs with the fracturing of Lydia’s psyche, I realized I’d become completely immersed in not just a world but a worldview. And it all comes back to the way Field rewires our expectations. Beginning with lengthy, languid dialogue scenes only to land at a place as disorientingly jagged as Tár does is a hell of a trick, and Field makes it look effortless. I’ve never considered myself a fan of Field in particular, but now I really have no choice. This script is that much of an achievement.

I’ve been a bit surprised by the backlash that’s hit Women Talking this season. Watching the film, I believed I was watching something essentially flawless. Yes, it’s stagey, and the performances befit that—there’s an odd, stilted tone to much of the film in keeping with the fact that this is as much a feature-length conceptual debate as it is a story.

On the other hand: what a story! I can’t count the number of times I was shocked by a reveal, or gutted by some switchback in the proceedings. This is a movie about women talking, and I don’t want to generalize it into something universal. Rather than making me feel I was seeing something I recognized, I felt a glimpse into worlds and perspectives I couldn’t, and I felt brought into that world in a way that was generous but stern, never allowing me to get comfortable enough to say I was “enjoying” anything.

At the end of the day, the challenge of any movie titled [demographic] Talking is to make the ensuing product feel cinematically dynamic. A lot of the effect comes down to the directing, but if Elvis is all editing, this movie is all screenplay. Were the words coming out of the performers’ mouths not startling and arresting enough, there would be no movie. Instead, we have one of the best of the year, and I’m genuinely shocked anyone feels differently.

Some mischievous part of me wanted to give Swinton both Best Actress prizes given that The Eternal Daughter is a two-hander between Swinton and herself—she plays both the lead, and the lead’s mother, and I can only think of two more characters off the top of my head. So say this one represents both performances—and one really can’t exist without the other (which is something of the movie’s theme, which isn’t fully revealed until a last shot that gives Tár a run for its money as the year’s most startling).

The mother role isn’t particularly showy. But it’s essential in its quiet groundedness. It’s not the first time Swinton has performed under immense amounts of makeup (and compared to Suspiria, the makeup here is downright understated) but her embodiment of age is about more than just looks. There’s a palpable history to the way she carries herself, but more than that, she manages to convey a real dynamic between herself and her scene partner…herself. It’s hard to even imagine the task, and yet it feels seamless.

I wasn’t a massive fan of Joanna Hogg’s Souvenir duology, but The Eternal Daughter laid me flat. A one-handed two-hander. How can you not give that some credit?

Michelle Williams has gotten most of the attention for The Fabelmans, but it’s Dano who consistently knocks me out. I’ve seen the movie three times and am probably cruising towards a fourth viewing, and I keep discovering new pockets of depth and nuance. No movie moment this year has gutted me quite like his micro-wince between chastising his son for not taking better care of his trains and doubling back a moment later to suggest they play this weekend. There’s a subtlety to the agony implied by that pause that befits an actor who’s been blowing me away for more than 15 years now (since at least Little Miss Sunshine, the movie I first discovered him through).

I said no movie moment has gutted me like the chastisement-to-regret flip, but no, there’s another: the moment that the son he once chastised throws his arms around his dad, and Dano gets to process his shock and then his immense catharsis. I feel a surge of emotion just writing about it, and the whole unspoken chain of micro-feelings lives and breathes on Dano’s face. It’s an understated performance, but it’s the lodestone of the movie for me. He’s playing a character who can rarely speak his feelings, but the performance says everything the character can’t.

I joked on Twitter that this movie is essential representation for flawed dads who are trying, so maybe that bias accounts for how clear this win is to me. But I’d say it’s more that I have a lens onto the immense inner world Dano and Spielberg created. It’s a painful lens to gaze through, but in Dano’s hands, it feels manageable.

This one was a lock for me back in January and nothing has changed. Like Women Talking, Good Luck to You, Leo Grande is an entirely stagey movie (call it Woman Talking) but that just means it’s a showcase for one of the best performers we have. Thompson has to play someone fairly unlikable for most of the movie, but that frustrating quality only highlights how innately appealing she is, suggesting complexity that needs little elaboration. It’s all there on screen in a way it can’t have been on the page.

It’s hard to talk about this performance without talking about the closing moment, but I won’t. I imagine a lot of people still haven’t seen this movie, and I hope I guide some more viewers towards it. Let’s just say Thompson gets to play vulnerability in about a hundred different ways, and the last moment is a culmination of all of them, but a moment of tremendous unspoken catharsis as well. This movie was a massive tearjerker for me, and as good as Thompson’s co-star, Darryl McCormack, is, she carries the bulk of the emotional weight. She’s the tearjerker. She’s just as good as ever here, and maybe even better.

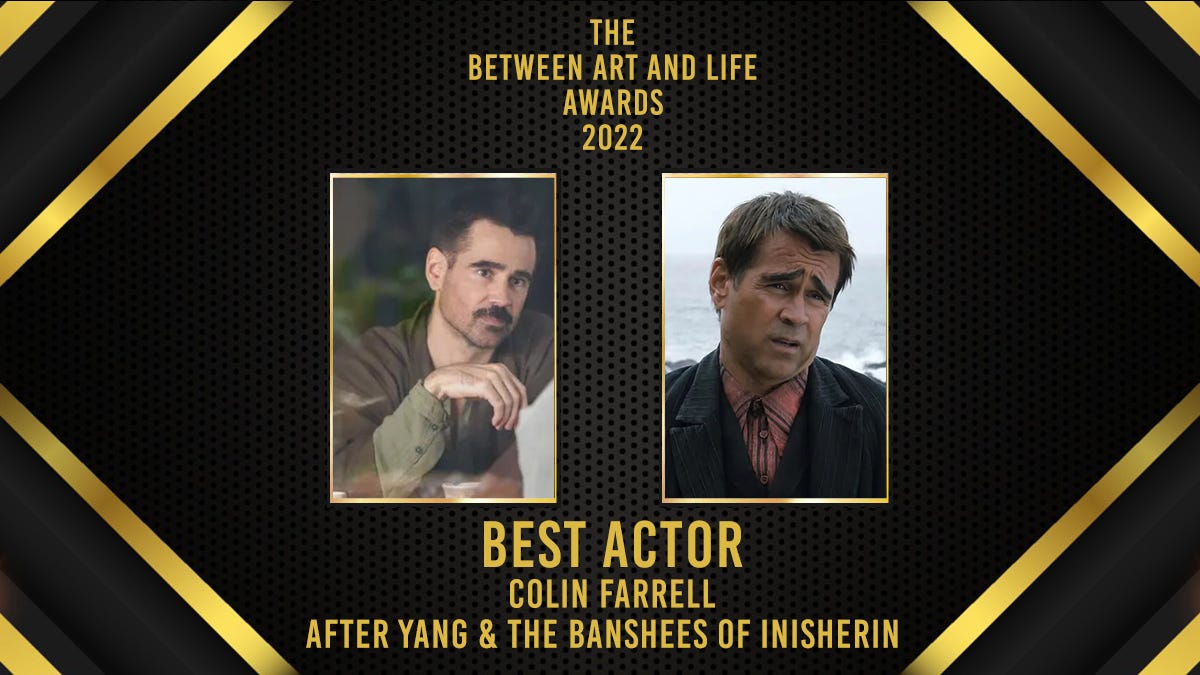

The Boston Society of Film Critics allows for double wins, and there couldn’t be a more deserving nominee for a double win this year than Farrell. It’s pretty common by now to point out that he’s become a real Brad Pitt—someone positioned as a matinee idol only to reveal himself as a crackerjack character actor—but Farrell has maybe bested Pitt in that department. And by bookending 2022 with two performances of bruised vulnerability that have a clear kinship despite being completely different flavors of grief, he had about as powerful a year as anyone I can think of (there’s also The Batman, but…I’m not giving him a triple win, I’ll say that; there’s also also Thirteen Lives, which I didn’t see…in any case, what a year!).

This is a truly balanced double win; I had Farrell penciled in for this category all the way back at Sundance and nothing else rocked him from that spot in particular…until he himself gave an absolute knockout of a lead in The Banshees of Inisherin. It’s a truly bizarre performance (something of which Farrell is clearly capable after his work with Yorgos Lanthimos, who evokes a whole other type of strange). He’s endearing yet annoying, sweet yet bitter, and wounded all the way down. It’s a perfect complement to After Yang, in which he joins Dano in the pantheon of cinematic flawed dads. It’s a performance as understated as Banshees’ is showy, two sides of a clearly matching coin. I’d watch either of them any day, and primarily be doing it for his performance. He’s a perfectly malleable actor, a clear gift to any director. I can’t wait to see who he works with next. (Ahem, Paul Thomas Anderson, looking at you buddy.)

As time goes by, the 2022 movie I’m feeling most compelled to revisit is White Noise. What a gorgeously odd film, a high-wire act that achieves the seemingly impossible: translate Don DeLillo’s gorgeously odd book to the screen. Baumbach conjured a vibe and tone I’ve never really seen before, satirizing everything from consumer culture to the basic facts of human interaction.

Those human interactions are the entire nut of the cinematic White Noise, and the woozy affair would never stay aloft without the ace cast that Baumbach assembled and marshaled into some kind of disharmonious harmony. There are stars Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig, of course, but their tricks can’t carry an entire movie. Instead, my mind is pulled back to peripheral characters like Don Cheadle’s professor of Elvis studies (a character close to my heart for reasons that won’t surprise anyone who’s been reading this newsletter for more than a week), who gets into a virtuosic verbal duel with Driver’s jealous professor of Hitler studies. And then there are the four kids who round out the nuclear family at the heart of the story, none of them recognizable faces but all of them absolute pros. Driver may be the star, but this is an ensemble movie through and through—no performance could function without the others supporting it, and it’s a marvel that Baumbach managed to coax a performance style that cohesive out of performers of any and every age. I can’t say every element of this movie worked for me (not sure this one needed a curtain-call dance number), but no large cast has worked better together. Therein lies this unusual movie’s true magic trick.

It always seems a little odd when Best Director goes to anything aside from the director of the Best Picture winner, but I just can’t help giving it up for Jordan Peele here. The way he’s gradually expanded the scope of his storytelling, going from the chamber horror of Get Out, to the grander surrealism of Us, and now to true blue blockbuster grandeur, has been one of the most exciting trajectories moviegoers have gotten to observe in recent years—and that’s to say nothing of the fact that before Get Out he was known resolutely as a TV comedian. There hasn’t been anything like the Jordan Peele story. Maybe you could compare him to Mike Nichols, but then again…could you? Or does the entire delight of Jordan Peele lie in the fact that he’s incomparable?

Nope is not one of my favorite movies of the year, but there are few I admire more. The performances range from the understatedness of Daniel Kaluuya to the outrageousness of Steven Yeun (who gets to play a wide spectrum of performance styles all his own), from the boisterous joy of Keke Palmer to the doom-laden grousing of Michael Wincott—and let’s not forget the comic relief ringer that is Brandon Perea. That variance in style shouldn’t make sense, but Peele pulls it all into harmony, and all the while finds the intersection of sci-fi and horror, grounding everything in a recognizable feeling of emotional realism. I can’t think of a greater feat of direction than that, whether this year or just about any other.

This is another slam-dunk easy one for me. You can have your Decision to Leave, your Return to Seoul, what have you. RRR is the most movie of the year, and to me, sometimes most = best.

I still desperately wish my first encounter with this film hadn’t been in Netflix’s Hindi-dubbed version, but even the odd hollowness of a dubbed movie couldn’t distract me from the power of the visuals. The only comparison might be Mad Max: Fury Road, but even that movie, for all its visual dynamism, only played in one storytelling key. RRR is orchestral storytelling, and its orchestrations are maximalist in the extreme. Maybe I’ll see something else as wildly impactful as this movie in my lifetime. If so, I’ll consider myself quite lucky.

I’m at a bit of a loss on how to sum up The Fabelmans in just a few words. I’ll have quite a lot of words on it soon elsewhere, and it’s going to take all of those words just to get at something like the heart of why this movie matters to me. It’s basically this newsletter’s thesis—that the most interesting space there could be is the space between art and life—made manifest. I’ve never been a massive Spielberg head; I’m an admirer more than I am a fan. But this movie has handily made the leap into my pantheon of favorites.

I always feel a sort of low-lying stress when I passionately love a movie that plenty of my brilliant friends consider garbage. But some cocktails are just specifically designed for specific people, and when a story deals with the delicious agony of existing as a parent, child, and human being in a world that only makes sense when viewed through the prism of art-making and art-sharing? That’s a movie designed to hit the bullseye for ol’ Ethan Warren. When it’s co-written by the writer (Tony Kushner) of one of my favorite plays (Angels in America) and directed by someone who seems to speak movies as a primary language? Call it treacly. Call it fakakta. I’ll call that an irreconcilable difference of opinion. There’s no real competition for me. The Fabelmans is the best picture of the year. Now get the fuck out of my office!