This Is My Fascination, Vol. 1

Welcome to This Is My Fascination, a new occasional conversation series I’m rolling out at this newsletter this fall. I’m thinking of these conversations as sort of like transcribed podcasts—I’d say more, but instead, we can just dive into the first installment, which sets up the concept right off the bat.

My first guest is B.C. Wallin, a writer whose work has been featured at Bright Wall/Dark Room, Inverse, Little White Lies, and elsewhere.

Note: this conversation has been edited for length, style, and clarity.

We should welcome the readers to a brand new series that I have decided to call This Is My Fascination. Does that ping anything for you? Do you get what I'm going for with that title?

[B.C. considers the question]

There's no reason it should. I'm going off of the Who: This is my generation. So, This is my fascination—talkin’ ‘bout my fascination. And this is your series to a certain extent. I asked you—because I think of you as someone with interesting ideas, and a mind that I like—if you had any ideas for a column like this. And I knew that, very quickly, you would have a good answer. And you did. And that answer was, basically, I'd like to know what people are fascinated by. And I was like, That's so good. And right out of the box, I asked you what your answer would be. And it was so good.

So what is your answer? What is your fascination?

I have been thinking a lot about the Moon over the past several months.

Terrific. And you gave me a rundown of ways you have been thinking about the Moon—do you want to give, like, a table of contents for the reader of ways we're thinking about the Moon?

The ways that I primarily am thinking about the Moon are: filmically, poetically, and religiously.

That sounds like a newsletter to me! So how about we get started with the filmic Moon? What have you been thinking about?

So as I'm sitting here, I'm looking across at my shelf of Blu-Rays, et cetera, and I have one section just dedicated to the Moon and otherwise space-based pictures. If you were to look at my Moon section, you would see: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Apollo 13, Interstellar—which is not actually a Moon movie—First Man, Ad Astra, and For All Mankind.

Oh, the the documentary?

Yes.

Not the the TV series collected set, which would also work.

I still haven't seen it -

[gasp] Good moon stuff!

A friend, Avishai Weinberger, has been posting about it enough on Twitter over the past few years that I really want to get to it at some point.

Such good Moon stuff. You don't have Moon on the list.

I actually do not like the movie Moon. I have not yet developed a positive relationship with the filmic works of Duncan Jones. But hey, maybe one day. You'd think that Moon would be right up my alley. I like Sam Rockwell. If I could have more than one Sam Rockwell—spoilers—in a situation, I would probably appreciate that. And I do appreciate the Moon. So all of that should be up my alley. And yet sometimes those things that you think are precisely engineered for yourself end up not being what you're looking for. And the most interesting things are those works that you never really went in expecting would be for you.

You sent me the clip from Ad Astra as homework for this. Why is this a clip that that was meaningful to you?

I think this clip is a perfect microcosm of the larger interest that I have in the Moon on a filmic level. It was shot by my favorite cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema—at least my favorite cinematographer of the modern era—and it was shot in a desert using infrared technology, this really cool visual language. But it represents the Moon as a physical space to exist in. I think that a big part of the appreciation of the Moon is seeing it at a distance. And then getting closer makes it even more poetic and more something that I want to appreciate. It's stark, it's barren, it's black and white and gray—there is no color, there's no atmosphere. Even with the assumption that there might be water, or ice, under the surface, it still is so empty and devoid of life. Nobody looks at the Moon and says, We're gonna live here without a lot of infrastructure to make it survivable. It's not a space to exist in for humans. And I think that’s sort of beautiful, for something that is the closest celestial body to us—if that's the right term—the closest thing-that-we-can-go-to is this wasteland that we've been staring up at for the entire existence of humanity.

And in the movie Ad Astra—which is a movie that I saw in theaters at the IMAX at the AMC Lincoln Square in New York City, which is my favorite screen to see any movie that I can see big, it's this huge screen, two stories tall—I went there, I saw Ad Astra, and I walked away kind of underwhelmed. Yet now, when I'm thinking about the Moon, and when I'm feeling this appreciation for it, I found myself drawn back in to this one movie. The same way I started watching the movie Steve Jobs over and over and over again, it was by watching a YouTube clip here, a YouTube clip there, until you finally find yourself engaging with the work as a whole and finding something different from what you had originally gotten when you engage with it.

It's a gunfight that's silent for the most part. And the movement is so fascinating, the way that these racing carts are interacting with gravity on the Moon. But for me, what's more interesting is that thing I said about starkness and and unlivability.

My supposition has always been that every space movie is a horror movie. Does this make sense to you? (And I'm talking hard sci-fi, not Star Wars.)

I think that that is one way of looking at it. I think you could also say that every space movie is a ballet.

You could! And we will.

I think there is something dancelike about being in zero, or limited, gravity. There is also something that makes the astronauts on the Moon look like toddlers with bunched-up diapers—it's not always elegant. It is otherworldly.

And it is so, so close to death. You are never closer to death than when you are in space. You could die so many ways. And it would be - well, I was gonna say, It'd be so bad, but it would probably be really fast, most ways. It's just so scary. Every movie about the Moon, all I think about is how much I don't want to be there—to quote Ernie from one of my favorite songs, I don't want to live on the Moon!

It's a good song. And sometimes I feel like that, and sometimes I feel not like that. My wife and I actually have an agreement. We've spoken about whether or not I'd be allowed to go to the Moon, or to space in general. Because, to my knowledge, there's never been an artist to go to the Moon. Maybe in space. But there's a very limited amount of people who've been on the actual surface of the Moon. And there's only so much you can capture about something from a distance, although we've been doing it for so long. But when I started thinking a lot about the Moon, I asked my wife, Can I go to space? And she said, No. And then I said, But what if I want to go to the Moon? And she said, No. And then I said, Well, how about if space travel becomes as familiar and accessible as air travel is today? And she said, OK, maybe.

It’s sort of the They should have sent a poet theory, right?

Yeah. The Moon has captured our imagination for so long. In terms of film, I think about Journey to the Moon, Georges Méliès, one of the earliest and most iconic films of the birth of cinema. I think about Moulin Rouge, dancing in the sky with a singing moon in the background. Moonstruck, Shrek -

Joe Versus the Volcano, have you seen that one?

I love Joe Versus the Volcano. The Moon is something that we always want to be bigger and closer. In art, we're representing it in these magnified ways. We feel a kinship to it of some sort. And maybe that’s just because it's the only thing in the sky that we can actually see in any form of detail. The Sun we can't look at, and the stars show nothing but pinpricks of light. The Moon is the only thing that we have detail to appreciate without resorting to cameras and telescopes.

Something I love about Moonstruck is that—it's sort of astrology adjacent, this idea that the Moon is basically driving everybody mad. There's sort of an ecstatic poetry to that movie—by the writer/director of Joe Versus the Volcano, I guess, so he's he's got some skin in the game when it comes to the Moon.

Should we highlight any other Moon movies? Apollo 13?

Apollo 13 is one of the most tragic moon movies there is because here's a guy looking out the window, passing just by. And I'll tease a little bit of the religious aspect, because I am Jewish Orthodox, practicing. And one of the things that we do every single month—it feels like one of the lesser known practices, outside of our circles—is that we actually go outdoors on a Saturday night, once a month, to bless the Moon. Whether it's blessing the Moon, or making a blessing upon seeing the Moon, that's semantics. But one of the things that we do as part of that process is that we dance up onto our tiptoes, and we say the phrase, Just as I dance toward you, and I still can't reach you, so may my enemies never reach me. But this thing that has, for me, over the past year, transitioned from a line that we say to something that actually feels meaningful is, however far we reach, we can't touch the Moon. And so I think of Tom Hanks sitting there, two generations of—or, two iterations of spacecraft after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. And there he is looking at the Moon. But he can't get there, and he's never going to get there, because how likely is it that you're going to get sent on a Moon landing mission twice?

And, it occurs to me, you could never touch the Moon. You can touch the Earth. Nobody will ever touch the Moon, so far as I can understand the science of it.

Unless, of course, we're able to build some sort of biome that can lock in the existence within the moon so we could be on the surface. But yes, exactly, it'll always be through barriers. It'll always be through glass, through glove, through boot.

One of the first movies where I ever saw the Moon depicted was Superman II. Superman has just thrown an exploding elevator into space, rescuing people at the Eiffel Tower, and that exploding elevator triggers a breaking of the prison that holds General Zod and his two compatriots, who had been imprisoned in Superman and also in the recap at the beginning of Superman II. And so, newly freed and exposed to the rays of the Sun, the three Kryptonians land on the Moon, and encounter a space mission in which at least one astronaut is on the Moon recording things. And they destroy this guy. It speaks exactly to your fear of the Moon, and space—I think one of them pulls a patch off of the spacesuit, and then, of course, combustion, or death, or suffocation, or whatever.

Can you tell me a little bit about For All Mankind, the documentary? I have not seen it, but I understand it to be a seminal work.

It's fantastic. For somebody like me, who is less interested in the science of it all, and the specificity—I don't really care about remembering specific years, and details, and why scoop up this piece of the Moon, or which crater they landed in. I'm reading Norman Mailer's Moonfire, so I'm getting all the details about Apollo 11, and the mission—some of it permeates, and the rest of it just floats around. I'm appreciating it on a more surface, or artistic, level.

For all Mankind begins with a quote: During the four years between December 1968 and November 1972, there were nine manned flights to the moon. 24 men made the journey. They were the first human beings to leave the planet Earth for another world. This is the film they brought back, and these are their words. And what I really like about that opening is something that is in one of the essays in the Criterion release: that this is not about America, patriotism. This is not about individuals. This is about humanity reaching out to the Moon, to something outside of ourselves. The idea of the title is, they didn't do it for the glory of any one body. They did it for all mankind. And I think even inasmuch as space travel and NASA and all that will always be tied to politics in some way—the choice to, or not to, travel to the Moon is inherently a political decision because of how tied it is to economics and manufacturing and labor and all sorts of stuff -

Nationalism, to an extent—to a large extent.

One hundred percent. And the first time you see the American flag planted on the Moon in For All Mankind, it feels almost garish, because of how anonymizing the entire movie has been. It's a movie made up entirely of footage shot by the astronauts, or shot from the outside of the spacecraft, or what have you. And all of the narration is anonymous. There's never a lower third that identifies who's speaking, there's never a talking head where you see somebody say, Well, the thing about going to the Moon is… It's all about these people just engaging with their experiences in this way that feels humanizing. Almost like The Old Man and the Sea or something like that. It's not them, it's us.

You mentioned Interstellar. What's the bridge between Interstellar and Moon canon?

Interstellar is in my space section. I wouldn't consider it a Moon movie because I would be precise about if it has the Moon or not. But in terms of what I'm looking for, it is engaging with the unknown. I think that the last planet they go to in Interstellar, of the planets that the characters are trying to see if they are viable for human life, that planet has a lot of that quality that you look for. It feels otherworldly, it feels actively harmful to humans, if not neutral at best. We live on this one planet, surrounded by so much distance, that is livable for humans, that actually supports our desires and our experiences, that we can breathe and eat and survive. And anytime we try to step a foot out the door, the universe is telling us, You don't belong here.

That's why every space movie as a horror movie! This sort of goes back to 2001, because the first time I saw that movie, it played to me like a slasher. And I went into school and I said, I saw this really scary movie—2001: A Space Odyssey. I was in seventh grade. And kids laughed at me. I don't think any of them had seen it. But they were just like, That's not a scary movie. Your bar for scary is pathetic, seventh grade Ethan. But that movie—I said it before, I'm just coming back to the same point: you can die so easy in space. You can die pretty easy here, too, but not that easy.

Yeah, it doesn't take losing a patch of of your clothing to die here. And 2001: A Space Odyssey is a scary movie to a seventh grader, I'm sure. It's interesting that nobody dies on the Moon from any of the conventional ways you would die on the Moon. It's more of the engaging with the unknown. But yeah, that shot from later on in the movie of one of the astronauts in fast-motion tumbling through space, disconnected from the one tube that was that was his breathing apparatus. It's the fear of traveling beyond our safe boundaries that is so imbued in every space experience.

Are you a Ray Bradbury person at all?

I read Fahrenheit 451 and I own a copy of The Illustrated Man.

Illustrated Man has the story I'm thinking of. It's called “Kaleidoscope,” and it's about astronauts—it's sort of the George Clooney in Gravity thing, astronauts are drifting apart from each other and are communicating while they can. That's so potent to me. But that’s space stuff, not Moon stuff, so we should stay on track.

In terms of literary experiences with the Moon, I have a limited perspective on that. There's one story by Italo Calvino that I love, “The Distance of the Moon,” in his Cosmicomics, a collection of short stories that are often engaging with the world in scientific or mathematical terms. And “The Distance of the Moon” is a story about a time where the Moon used to be closer to the earth, and it would cycle around the Earth, still in its monthly pattern, but what it would do is that when it would get close enough to the Earth, it would create this gravitational field where people could go out in boats and put a ladder up in the boat—a little similar to the Pixar short film La Luna, which is also a good Moon movie. And the fishermen, or sailors, would go out into the water, and would throw an anchor up onto the moon, and then would climb up there and would milk it, because it had this sort of weird, milky liquid.

I didn't think we were going towards milk the moon, I admit, even seconds before you said it.

But the thing that interests me about that is there's a character in it who is almost nonverbal. Sort of weird. Nobody really understands him. Very awkward. But when he gets on the Moon, suddenly he dances on the surface. And it's almost like he has a distinct relationship with it. And the story is from the perspective of his cousin, or whoever it is, who's observing, and seeing this experience. There was something to me about this character who falls in love with the Moon. It’s such a beautiful way of engaging with this body.

There's a poem that I think about a lot when I think about the Moon, and it's very simple. By Andrew Michael Roberts, it's called “The Moon.”

all the other moons

get their own names.

It's very simple.

Less than a haiku.

Exactly. But it's this simple perspective on it: it's the Moon. It's not a named moon. It's not Io or any of the other ones. It's generic, approachable, unbranded, and yet so familiar—doesn't need to be branded. It's personal. We don't call it our moon, but it is the Moon. And there's no other moon that is the Moon. It's almost tragic, but it's almost personal. And that's where the Moon exists for me: in this space in between all those emotions.

I don't suppose you're familiar with the poem, Orlando Furioso.

I am not.

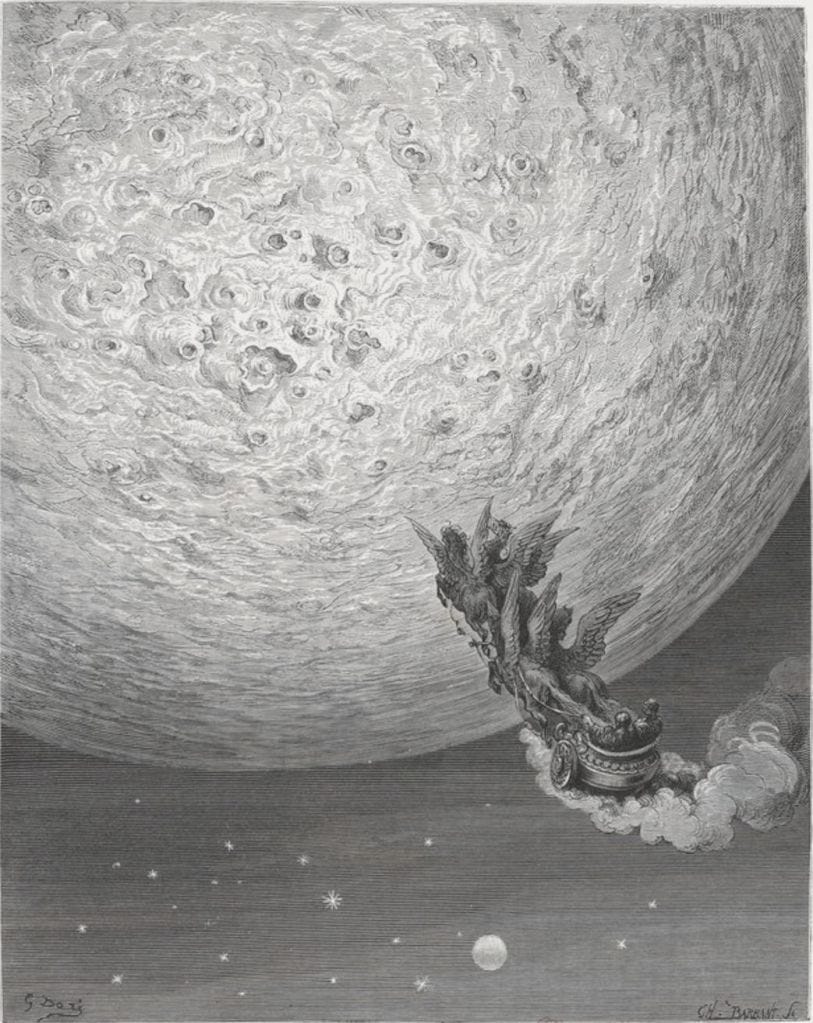

The epic poem. It's two volumes, two huge, chunky paperbacks. I wrote my senior thesis on it in college. It's this great, epic, mash-em-up of all kinds of iconography. The entire plot of Much Ado About Nothing is a subplot in this poem. Shakespeare just took it. There's a ton of Don Quixote in it. And Orlando loses his mind—he loses his wits. He's the protagonist of the poem, and I think his girlfriend cheats on him. And he loses his wits. And he has to fly to the Moon to get his wits back. I've always really loved that, the idea that when you go mad, your wits have gone all the way to the moon, and you’ve got to go all the way there to get him back. That's your epic quest to regain your sanity. Something about that has always felt potent to me. I think that's the second time I've said potent in the last hour.

It makes sense. I also like The Fabulous Adventures of Baron Munchausen, where he rides a cannonball to the moon.

Is that the book or the movie you're referring to?

I'm specifically talking about the Karel Zeman movie. I haven't read the book, and I haven't seen the Terry Gilliam version, either.

As much as I'd like to have some extensive and knowledgeable perspective, something that says, I began with Goodnight Moon and I continued with these appreciations, I don't have much poetic perspective. But it fits into the same basis of that filmic appreciation. Why does the Moon recur so much in the art that we have, and the stories that we tell? It's because it's accessible in that way—Look, but don't touch. You feel like you can approach it. It's so recent that the moon was actually accessible. 1969 is not that long ago in the scheme of artistic history. But this is still something that anybody who's stood out in a field and reached their fingers out and thought, What if?—it's Luke looking at the two sun on Tatooine. It's always teasing us and haunting us. Never the same from day to day, but still familiar.

I wanted to talk more about that thing I touched on surrounding Moonstruck, which is what it does to our bodies, and the Earth. There is that thing of, the Moon pulls on the tides, and so the Moon pulls on us, we are made up of water. What do you make of all that?

There is this interesting thing about the Moon that it is so tied to cycles of the tides, of menses, of the months. It's something that maybe we're feeling on a subconscious level. I don't honestly know how the Moon affects us specifically. But gravity is a powerful force as Interstellar, and Alfonso Cuarón [director of Gravity], would tell you.

I think that for me, I always think about that relationship of time and cycles on the religious level, because of how much it specifically identifies with the months. The standard calendar for the year is a solar calendar. The standard calendar for the Jewish year is a lunar calendar. It follows the Moon. And the months begin when there's a new Moon, many of the holidays fall on a full Moon. And there is ritual that connects to witnessing the Moon, and identifying the start and the end of the months. So in terms of the physical experience of the Moon, I don't know what it is, but I know that we feel something. And it's so primal that you can identify it through werewolves, and rituals, and poetry.

So is there more in the religion department?

I have so much that I can say.

All right, let's go.

So in the beginning, there was nothing. And per the telling of the Torah, there was nothing, there was darkness, there was light. And in the telling of the of the Genesis story, the light is concentrated into day, the dark is concentrated into night. And there are two bodies that become representational of those periods, the Sun for the day, the Moon for the night. And one of the first observations that Jewish theology makes about the way it's described is that they're called the great luminaries. And then later, they're referred to as the large one and the small one. And so there's this mythic story that is told, that is: the Sun and the Moon are both of equal brightness, and the Moon says, How can you have two kings share a crown? You can't have two rulers have equal power, somebody has to be diminished. And so God says, Well, then I will diminish you, thank you for volunteering. And the Moon becomes no longer a source of light, but only a reflection of light. And then we have the day is light and the night is dark. But according to some teachings, in messianic times, the world would see a return of the great luminaries, and there would never be darkness—the Sun would produce its own light, and the Moon would produce its own light.

And there's something about that story that sort of ripples out through every interaction that Judaism has with the Moon. We go out every every month, outdoors, to say, what is called in Hebrew, Kiddush Levana, or the Sanctification of the Moon. It follows the new Moon, the month being declared the Saturday before the month begins. There is an announcement made in synagogue: This is the day, on this day at this hour, and this many pieces of an hour, the new Moon will be sighted over the skies of Jerusalem. And this is a harkening back to an old ritual whereby people would go to court to testify to the new Moon. And then that declaration of what day the month begins would be passed out, originally, by beacons of flame over the hills and then later by messengers, because people were messing around with the beacons, and it's a whole thing.

One of the key pieces of text that's said in the Sanctification of the New Moon is that we pray for it to be to be fixed as it was originally—that there is something about the moon that represents, this world is not what the world should be. That feeling that something is wrong with reality, because we have this body that is rarely full, that's always missing something. And so all of that is this weird sort of yearning that is an undercurrent, especially as it gets repeated month in, month out. And not everybody always has it on the front of their mind. But for me, at least, especially as I've been thinking about the Moon, it's been something that I've been concentrating on more and more frequently.

Yearning really seems to be something that we keep coming back to, and you keep coming back to.

You want to hear an obnoxiously broad question? What is yearning to the human condition? What what are we exercising when we yearn for the Moon? Exercising or exorcising, depending on your preference.

We need to reach for something outside of ourselves or we would live sedentary lives. You could call it a curse, or you could call it a motivating factor of the human condition. But we always want more to build up, to reach. If it's not skyscrapers, it's the Tower of Babel. It's this yearning to be bigger, to be taller, but also to grab what we don't have. Contentment is is hard to accept. And it sucks! It sucks to be human, and to always feel like, I need to go beyond this.

But when it comes to the Moon, I, at least, think of it as: it can be a purification of this unholy desire we have, if you see it that way. Before we knew that there was ice on the moon, we thought going to the moon had no value to us, or little value to us. What, so Buzz Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong, and all the others could play golf, and hop around, and ride a rover? It's human exploration as a scientific endeavor, as a learning, and exploration, and potentially an outreach opportunity to to say, We're here, and we want to share what we have. And we want to learn from those who have what we don't. I know that if space travel became so regular that my wife would let me go, the Moon would be plastered with the billboards and advertisements that you see in 2001, and in Ad Astra. We'd commercialize, and conquer, and those of us who wished for not everything to be cannibalized by humans would say, Maybe there's another body we could go to, and we could live there peaceably, and just let things live. And then we'd go there, and then Elon Musk would sell real estate or something else. But because we haven't achieved it yet, it's always that idea of potential, and potential will always beat reality. And so this potential that we reach out to, it feels pure, in a way.

There's one story that I really like about the Sanctification of the Moon. There was a town in, I'm gonna say, the 1200s. It was sometime in the Middle Ages-ish. There was a plague—I don't know if it was the plague, but there was a plague. And this is sort of a touchstone that was looked upon several centuries later, when synagogues were closed down in 2020. The rabbis declared that prayer services could be held in groups of no more than ten. You need to have a group of ten to properly do all of the prayer services that are required—according to the best meaning of the rules, the Sanctification of the Moon should be done with ten people, should be done outdoors, should be done on a Saturday night, should be done on a clear night where you can see the Moon and not blocked by clouds, and it should be done between the third and the fourteenth of the month, so that way, the Moon that you're seeing is as new as possible.

During the plague, they went out on a Saturday night, under the open sky, and they looked up, and there were clouds covering the moon. And they were not able to say the Sanctification of the Moon. And Orthodox Judaism, the Halakha, following the strict rules, can be very limiting in terms of, there's this time when you can start, and this time when you end, and not before, and not after, and it's very precise. And here, in this moment, when there was this community despair of, We cannot greet the Moon, they went to the rabbis, and they said, Please, can we go out? And the rabbis created a leniency of one extra day where they were allowed to go out and do their sanctification and the blessings in the process, this process that includes saying, Shalom aleichem—Peace be unto you, to three people. And then through those three people saying back to you, Aleichem Shalom—Upon you there should be peace, there's this greeting, there's this ceremony that speaks to the Davidic dynasty, which is really a representation of Judaism not being in a state of diaspora, and this idea of the cycle of the Moon where just as the moon is big, and then it becomes small, and disappears, so, too, us, etc.

But this idea of—they were so sad they couldn't greet the Moon that rules were bent, because it would be a great despair for this community in a time of such struggle to not be able to greet the Moon. Ever since I heard about that a few months ago, I've just been thinking about that pretty much every single month, how important and personal it is to go out and reach out to the Moon, and to dance toward the Moon, even though you can't touch it. But to acknowledge this connection that has existed since the fourth day of creation, and continues on through now.

Do you have a fascination you want to talk about? Do you want to read about a specific someone’s fascination? Sound off and let’s get it on the books!